Dying To Keep Warm: Oil Trade And Makeshift Refining In North-West Syria

Entering into their 9th year of the war, access to basic humanitarian needs for Syrian civilians, both displaced and local communities continues to be a problem. Fuel for heating, cooking, and transportation is difficult to access and comes at huge financial and environmental costs. The former is a direct problem for households that often resort to using alternative means of fuel such as wood and plastic, while the latter will be a burden on the country in the post-conflict phase.

As documented in previous open-source articles, Syria’s oil industry has taken a heavy hit, leading to significant damage in production facilities, as well as oil spills and the rise of makeshift oil refineries through the eastern part of Syria, most notably in Deir ez Zor and Hasakah. These refineries were borne out of necessity as the professional oil industry crumbled soon after the peaceful revolution against the Assad regime turned into a bloody conflict.

Armed groups soon started to take over key refineries and oil fields, resulting in feeling staff and further stops to regular production; or else the refineries were targeted by the U.S.-led coalition, as well as Russian air strikes, after the Islamic State took over these areas in 2014.

The rise of makeshift refining, as crude oil could still be pumped up and exported, soon became a viable source of income for local civilians, as these unsustainable coping strategies were needed to compensate for unemployment. Armed groups also capitalized on these practices for income generation and smuggling networks to finance their war machines, making these refineries a common business in Syria.

Main findings

This visual investigation aims to identify the vast number of makeshift refineries that at one point or continue to be used in Syria, and the huge environmental health hazards associated with these practices for civilians working in this industry. These are the main findings of this visual investigation

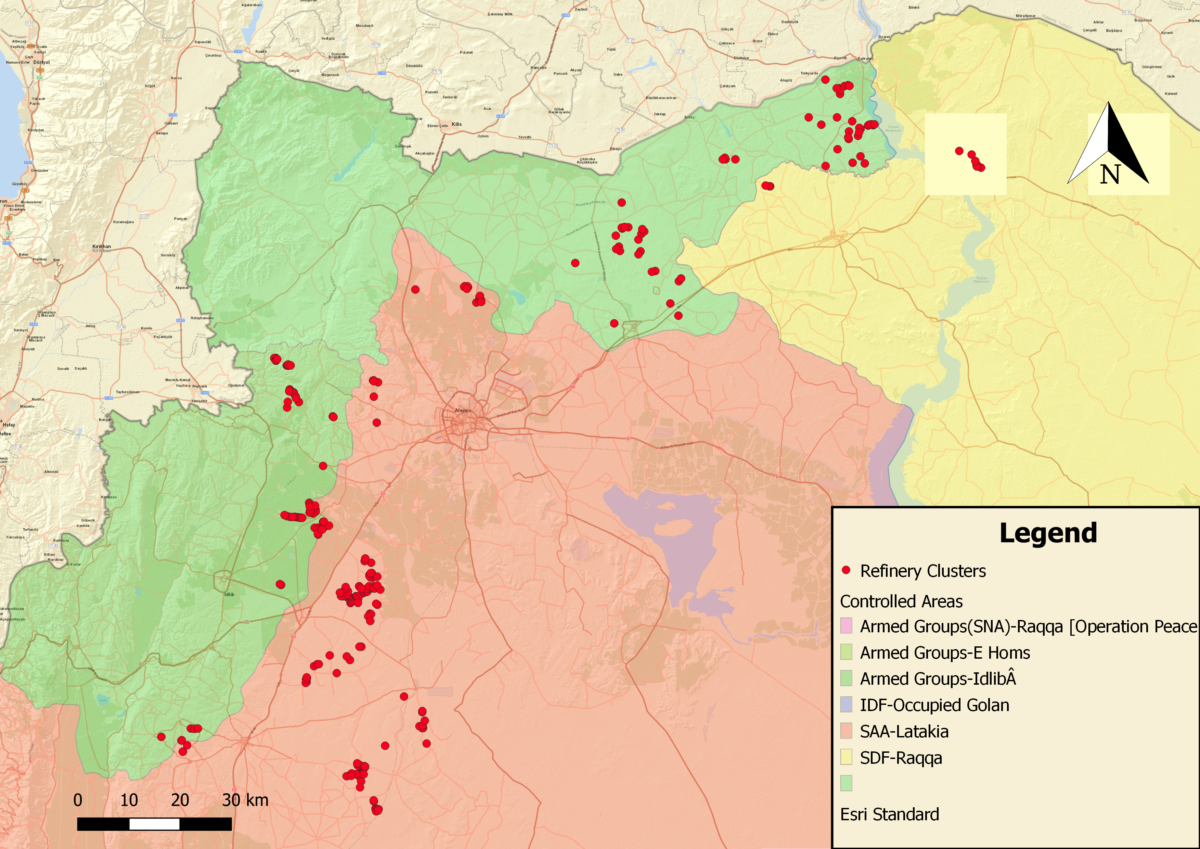

- Using opens source information and satellite imagery, we identified roughly 300 clusters of refineries with between 1500-5000 refineries that were built and at some time have been used.

- Knowledge and expertise on producing refined oil from makeshift installation rapidly increased throughout the conflict, with improved and more secure installations being built.

- Exploding barrels and frequent fires made these places a serious health hazard for workers, while people living nearby have faced additional environmental health risks from air and water pollution.

- Displaced civilians were employed as cheap labour in larger clusters of refineries, among them many children and teenagers, while living in nearby camps.

- Documentation shows that at least 10 makeshift oil clusters were bombed by Syrian and Russian fighter planes in the period 2015-2019.

- In Idlib and Aleppo, these refining practices stopped after regime forces captured the area, or when oil supplies were halted due to military developments.

Overview of clusters of oil refineries in north-west Syria.

“We only earn $15 a day but get cancer for free”

Our previous research articles on conflict pollution from the oil industry utilized open source information collection and remote sensing in order to help bolster understanding of conflict-driven toxic dynamics that could pose serious acute and long-term health and environmental risks.

Civilians working at the refineries are exposed to a range of deadly hazards. The heating oil drums can be very unstable, and incidents from north east Syria taught us that there were many cases of people being killed or severely injured from exploding oil barrels. If that doesn’t happen, the smoke and toxic substances can still cause acute health problems, as many anecdotal reports over the last years include oil waste infecting wounds, serious respiratory problems from inhaling noxious fumes, and sometimes even death from inhaling toxic vapours directly coming from the burners, which contain polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) that are linked to carcinogenicity and mutagenicity.

Then the question is what the long-term exposure will mean for the workers, many of them children. Fears of cancers are a commonly noted concern in all media reports and interviews with workers, while in practice it is also likely that the fumes have high levels of particulate matter and heavy metals from burning oil that will affect internal organs, in particular the kidneys. A full overview can be found in this table from the U.S. Department of Labour Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s booklet on oil spills.

| Hazardous Chemical | Adverse Health effects |

| Benzene (crude oils high in BTEX, benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylene) | Irritation to eyes, skin, and respiratory system; dizziness; rapid heart rate; headaches; tremors; confusion unconsciousness; anemia; cancer |

| Benzo(a)pyrene (a polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon reproductive [see below], formed when oil or gasoline burns) | Irritation to eyes and skin, cancer, possible effects |

| Carbon dioxide (inerting atmosphere, byproduct of combustion) | Dizziness, headaches, elevated blood pressure, rapid

heart rate, loss of consciousness asphyxiation, coma |

| Carbon monoxide (byproduct of combustion) | Dizziness, confusion, headaches, nausea, weakness, loss of consciousness, asphyxiation, coma |

| Ethyl benzene (high in gasoline) | Irritation to eyes, skin, and respiratory system; loss of consciousness; asphyxiation; nervous system effects |

| Hydrogen sulfide (oils high in sulfur, decaying plants and animals) | Irritation to eyes, skin, and respiratory system; dizziness; drowsiness; cough; headaches; nervous system effects |

| Methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) (octane booster and clean air additive for gasoline, or pure MTBE) | Irritation to eyes, skin, and respiratory system; headaches; nausea; dizziness; confusion; fatigue; weakness; nervous system, liver, and kidney |

| Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) (occur in crude oil, and formed during burning of oil) | Irritation to eyes and skin, cancer, possible reproductive effects, immune system effects |

| Sulfuric acid (byproduct of combustion of sourpetroleum product) | Irritation to eyes, skin, teeth, and upper respiratory system; severe tissue burns; cancer |

| Toluene (high BTEX crude oils) | Irritation to eyes, skin, respiratory system; fatigue; confusion; dizziness; headaches; memory loss; nausea; nervous system, liver, and kidney effects |

| Xylenes (high BTEX crude oils) | Irritation to eyes, skin, respiratory system; dizziness; confusion; change in sense of balance; nervous system, gastrointestinal system, liver, kidney, and blood effects |

The long-term environmental impact of these refineries could also pose serious risk to human health and local ecosystems and biodiversity. In particular, the storage of oil waste, collected in rivers, and the dozens of spills into local creeks or rivers, all serve to contaminate ground water and soil, and require clean-up, remediation, and monitoring. Yet often these environmental considerations remain absent or underfunded in post-conflict recovery programs.

The oil, meanwhile, isn’t staying in one place, and both the oil trade and expertise of (semi) makeshift refining is spreading throughout the country along the trade routes in the direction of Aleppo. This is also not without risks. Therefore, in this article we will be taking a look at how the practice of oil refining quickly took root in the north west part of Syria.

Stories of Syrian Crude

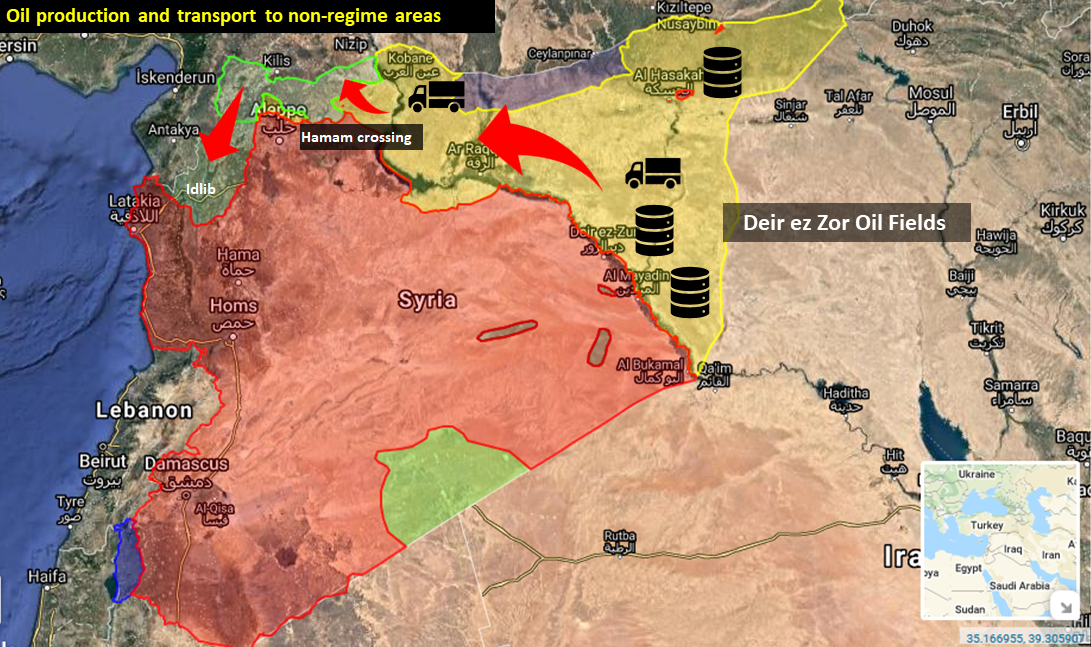

Most of the oil pumped up in the oil fields of Deir ez Zor and Hasakah is being exported outside the production region as these oil fields are heavily damaged, leaving hardly any refining and storage capacity behind. The practice of makeshift refining quickly spread in these regions since the onset of the conflict, with tens of thousands of small refineries appearing on the roadside, in backyard, and in large clusters to produce what locals call mazut, a low-level but functional form of diesel. Other refined products are benzine for motors, cars, trucks and kerosene for heaters in the houses.

The combination of an relentless bombing campaign by both the U.S.-led Coalition and the Russian Air Force severely degraded ISIS capacity to produce oil. With the rise and (and later fall) of ISIS and the mass displacement in these areas, the expert knowledge and know-how to build these refineries quickly spread to the west.

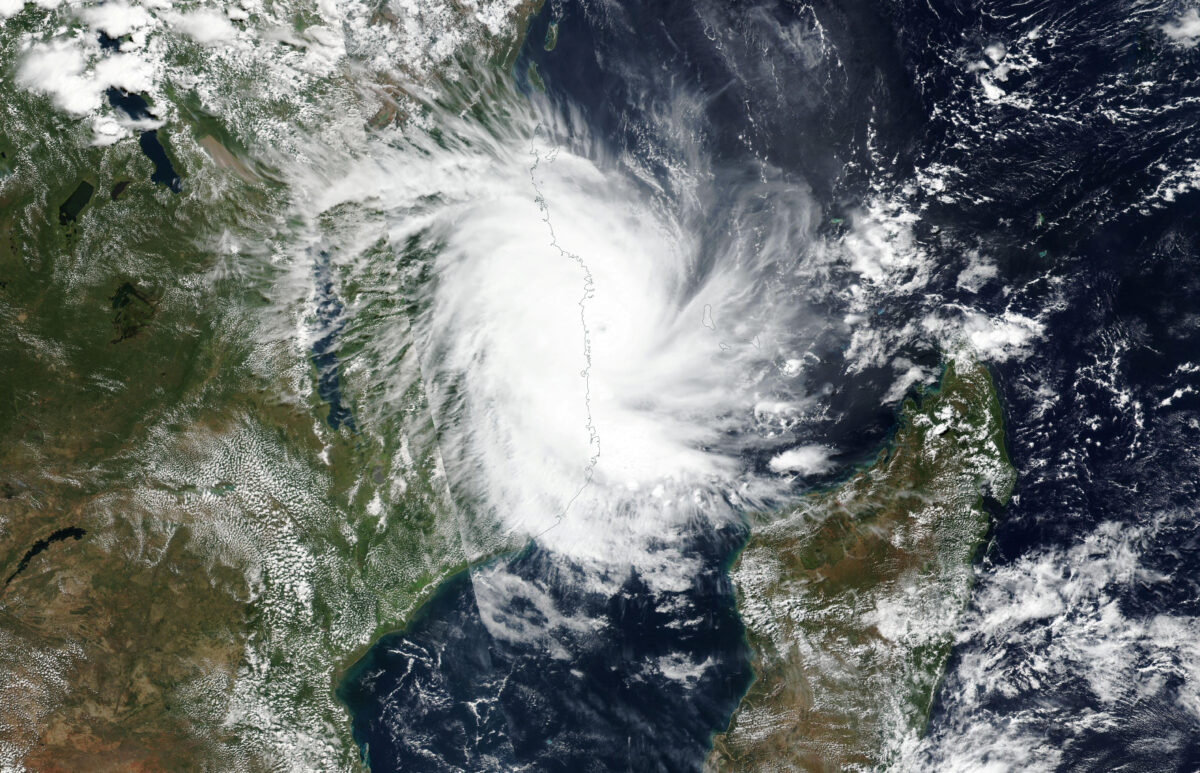

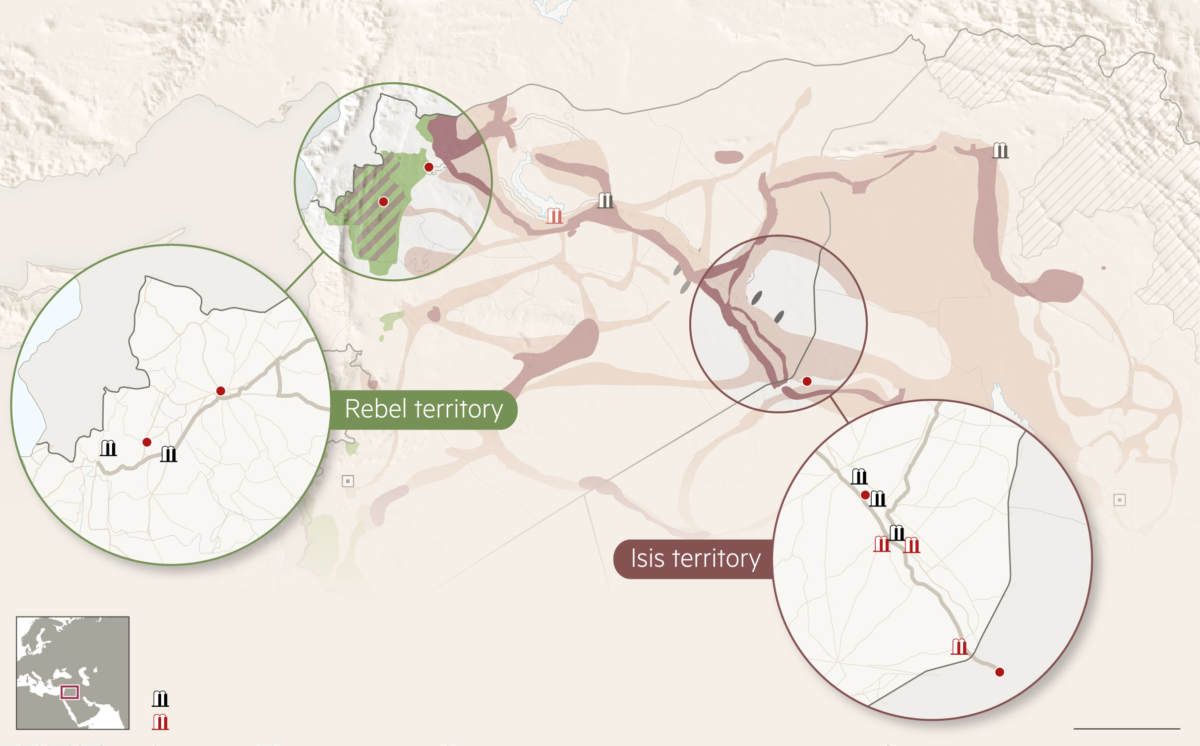

According to the Financial Times article linked in the paragraph above, from 2015 on, traders took the oil from ISIS areas and exported it to rebel held territories in Aleppo and Idlib, as visualized in the image below.

Oil trade Syria, Financial Times, 2015

Satellite Archaeology

For this research, we will mainly use Google Earth Pro (GEP) to see the development of makeshift oil production in this part of Syria. This also due to the fact that other free imagery such as Planet Labs and Sentinel 2 was either not yet available for that period, or difficult to process through easily accessible earth observation platforms such as Landsat 8.

Hence, we’re mainly sticking with GEP for high resolution identification. Considering the shifting power dynamics and economic activities, we searched certain areas using the “Historic Imagery” function in GEP, which was key to see the rise (and sometimes fall) of makeshift refining in various areas in north west Syria.

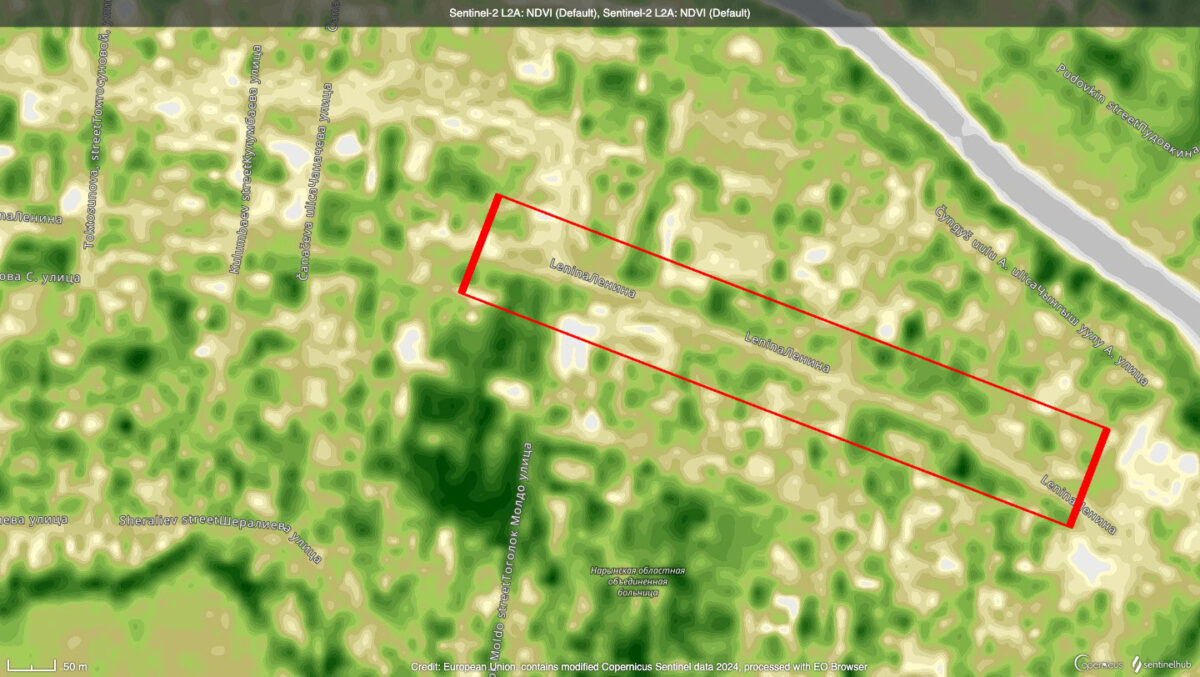

We also used Sentinel-2 imagery with 10 meter resolution provided through Sentinel Hub to scan areas for fires, smoke, and burned areas that could indicate refinery activity. In particular, the Colour Infrared (vegetation) bands proved to be very useful in identifying clusters, as the black spots contrasted well against the red vegetation colour. We also used Planet Labs that has almost daily imagery, depending on cloud cover, for possible confirmation from social media reports, using their 3-meter resolution. Finally, we used various English and Arabic keywords to search for open source articles through the last 9 years to learn about locations of artisanal refineries (often referred to as primitive refineries, oil burners, or makeshift refineries) and on Twitter searches.

Oil Trade Routes

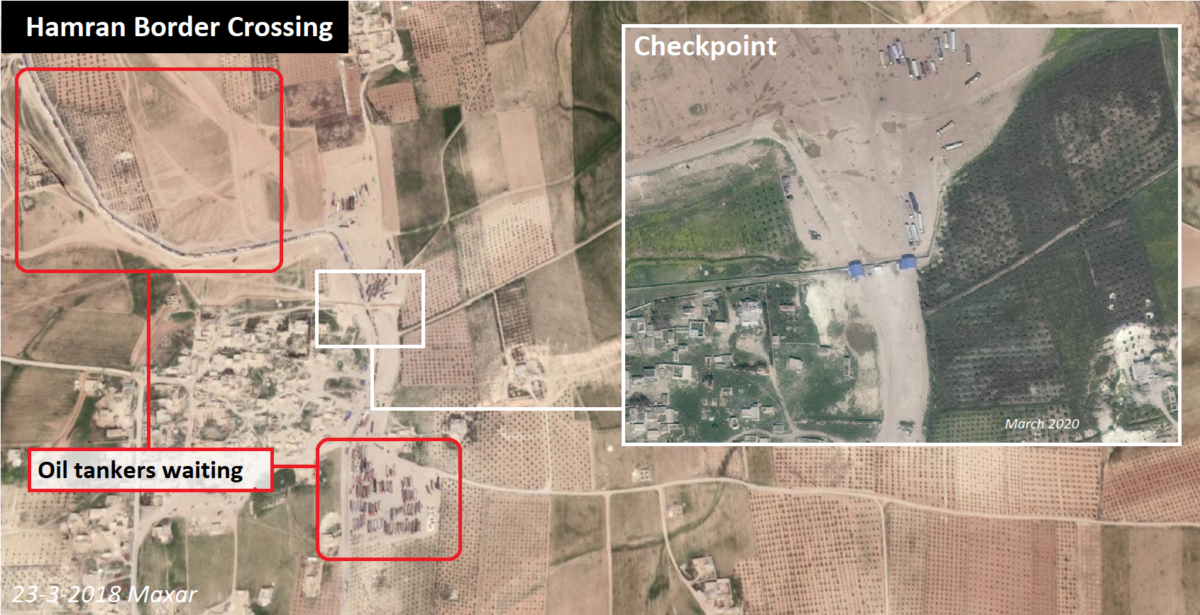

The crude oil was being loaded up at the oil fields in Deir ez Zor and Hasakah, and then transported by thousands of tankers through SDF-controlled areas. There were several points of entry in rebel controlled areas, with the largest one being the Hamran border crossing at the village of Umm al Jalud, west of Manbij, as documented by Twitter user @Obretix

there's also a more or less steady stream of oil tanker trucks from the oil fields in Hasaka and Deir Ezzor provinces to opposition held areas via Hamran crossing northwest of Manbij https://t.co/L3acUs1UUw (sat images dated 28 Mar 2019) pic.twitter.com/HCDmw6Z3Tp

— Samir (@obretix) April 28, 2019

the video referenced, of "the entry of tens of trucks carrying fuels from the controlled areas of the SDF to the controlled areas of the regime forces" shows oil trucks on the east-west axis in Manbij and Ayn Issa https://t.co/wuLnX1NuDm 1/5

— Samir (@obretix) April 23, 2019

On Google Earth Pro imagery, kilometres-long queues with oil tanker tankers can be seen entering and leaving rebel-held areas of northern Aleppo at the so-called Hamam crossing, as visible on the image below:

Hamam Crossing

Another entry to north Aleppo from SDF areas used to open north of the village Tal Rafay, where tanker trucks were spotted in 2017 entering and leaving northern Aleppo from SDF areas, before it was closed down at a later stage.

Tel Rifay Border Crossing, 2017

The map below shows the general trade routes for crude oil going from Hasakah and Deir ez Zor to north-west Syria.

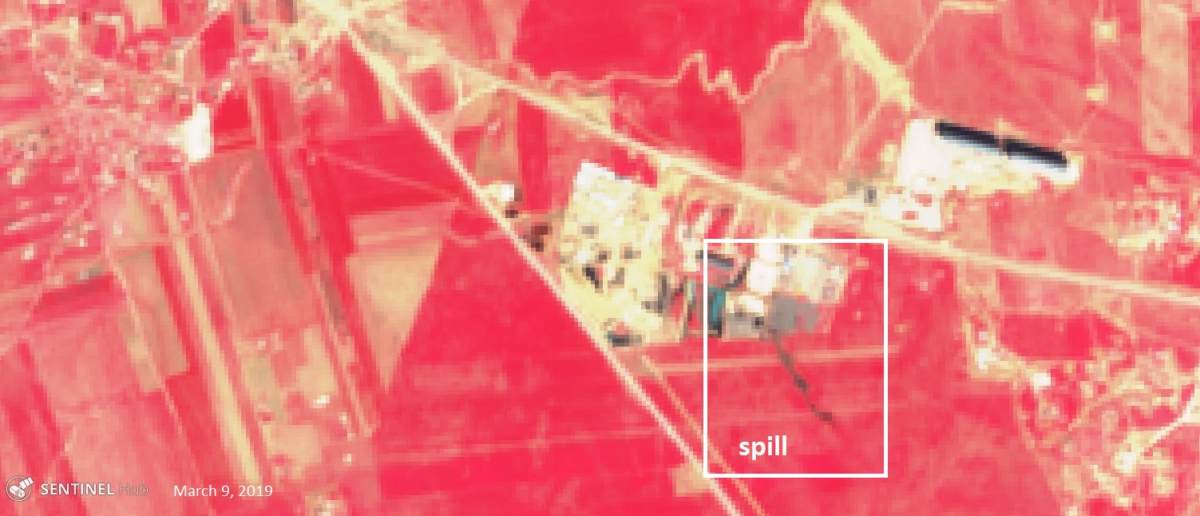

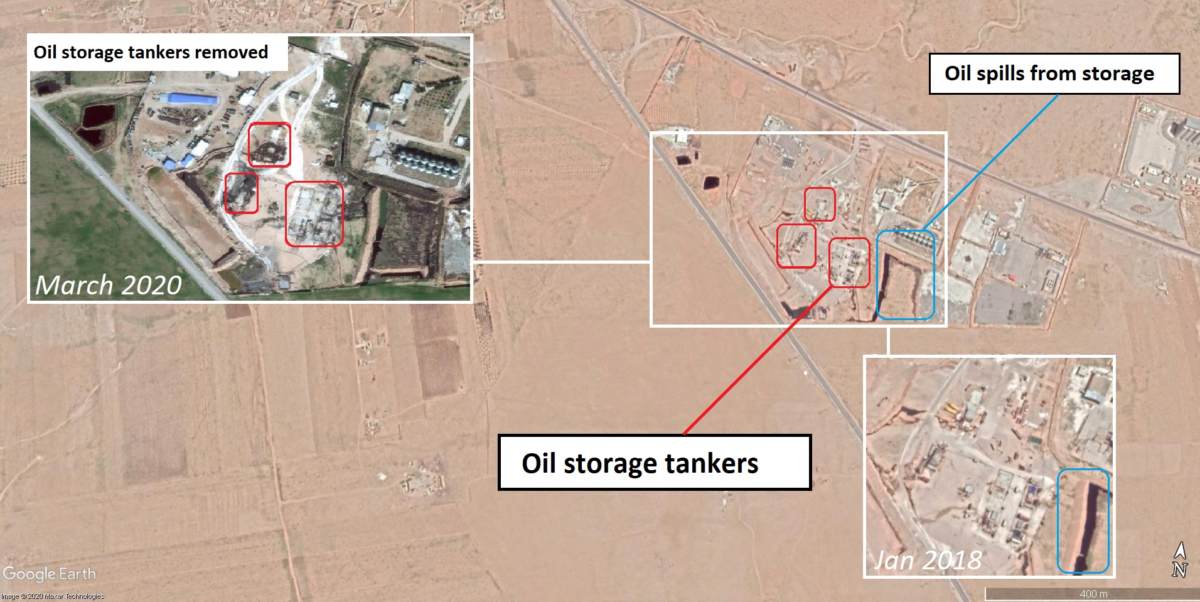

South east of the Qarah Qawzaq Bridge, which connects Aleppo with Raqqa province, also close to a former U.S. and current Russian airbase, there was also an oil facility located on the premises of the Grain and Cotton Depot. On satellite imagery from 2018, it can be seen that oil storage tankers were placed there, while Sentinel-2 imagery from March 2019 indicated some kind of spill occurred at this location — potentially, this was local oil waste from refining, or else oil tankers emptied their waste there. In November 2019, this waste stream was gone, both indicating clean-up and ruling out it being water, as the spill was visible for 9 months.

Grain and Cotton Depot Oil Storage, Raqqa.

The location seems to have been in use for at least a year, but recent imagery from 2020 indicates that the storage and processing of waste has halted, as the oil storage tankers have been removed from this location, potentially after the Russian take-over of the nearby U.S. air base in the end of 2019, after the Turkish led incursion into northern Syria in October 2019 and the subsequent Russian presence.

Oil storage at Grain and Cotton Depot

There are also reports of oil smuggling from SDF areas to regime-controlled areas in Deir ez Zor, but these seem to be mostly local gangs using boats, pipelines and trucks. But this is not likely to end up in north west Syria as the oil is mostly for local use in regime-controlled areas.

In the next section we will look at specific areas, the local dynamics of refining, and the living and working conditions at these locations.

Characterising Artisanal oil refineries

Based on the available video and photo footage, our previous reports on Deir ez Zor and field visits to north East Syria in 2018, there four distinct refinery versions.

Primitive refineries/roadside burners

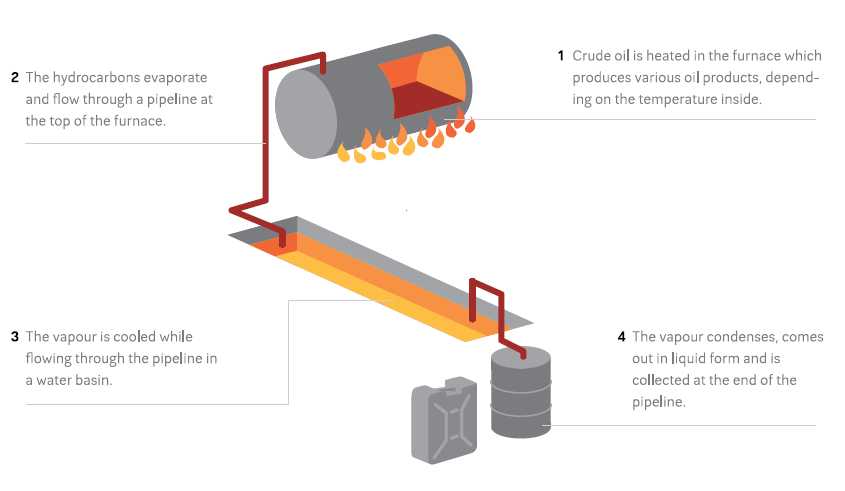

These refineries marked the beginning of the process, were documented in numerous media reports, and were easily visible on satellite imagery. They were simply constructed by digging a ditch, filling it with water, and putting a furnace at the end. Then a pipeline was put through the water ditch to condense the heated oil and collect at the end of the pipeline. Due to their size, these refineries didn’t produce a lot of oil per furnace, hence they can often be found with numerous furnaces and ditches at one location. In particular, in Deir ez Zor these types of burners were found in massive quantities from 2013-2016, as documented in our Scorched Earth, Charred Lives report from 2016.

Visualisation makeshift refining. PAX, 2016

Below is an example with images from a refinery in Tel Rifaat in 2013, as well as a satellite image in the left corner from Deir ez Zor to show how these refineries look like from space. Usually, they can be spotted by the ditch and the black spot at the end with oil waste residues, which blacken the soil around the furnace.

Larger Oil Burners

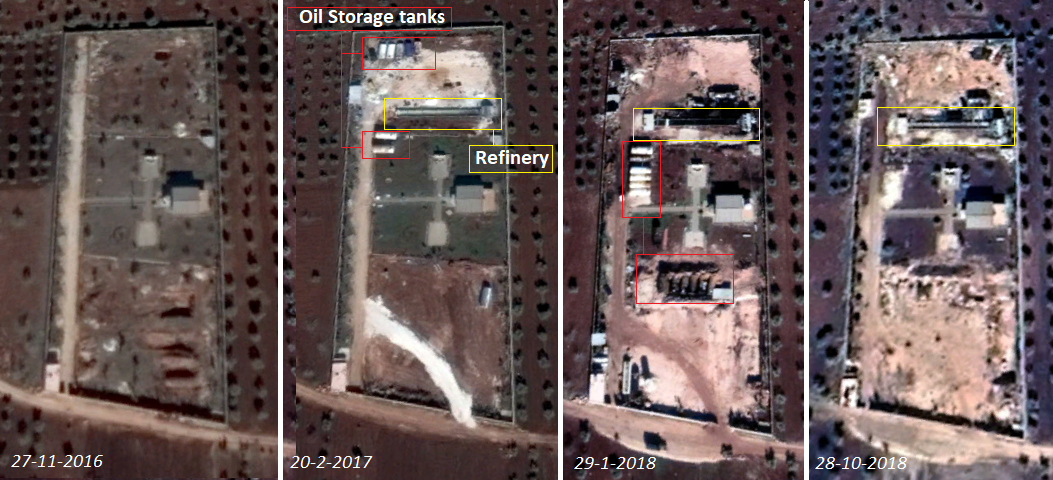

Size matters in oil production, and people working in the informal oil industry started building bigger and more professional versions. Soon, larger types of makeshift refineries were constructed with bigger tanks, multiple pipelines, and built-in bigger fortified constructions, sometimes above the ground, with basins with proper canvas inside to retain the water. Below is an example of these refineries in Idlib, constructed from this interview from 2017.

Idlib makeshift refinery 2017

Multiple Burners

There are also bigger versions with multiple burners built around one basin, as seen in the image below composed from various shots in a Al Jazeera item from Aleppo, in 2017. There are larger tanks, a larger basin, and multiple pipelines, yet still it needs to be manually fed fuel to heat the tanks. The blue canvas is notable at these types of burners, making them easy to spot on satellite imagery

Multiple burners per refinery unit, Idlib, 2017

Semi-professional Refineries

The traditional makeshift refineries used often proved to be unstable, resulting in frequent explosions, killing and maiming local workers. Hence, there was a push to build stable refineries with less manual labour to heat the crude oil, hence minimizing health and safety hazards for workers.

Tel Rifaat, 2017

Throughout the last three years, we witnessed the appearance of semi-professional refineries, where heating was done through diesel engines, or through vacuuming the oil tankers to quickly heat the oil. In the SDF-controlled areas, these types of refineries are now more common after the self-administration shut down the majority of roadside burners following complaints from communities over pollution and health hazards.

Two oil workers at a ‘vacuum’ oil refinery, Haskah, November 2018. Wim Zwijnenburg

The newer installations also have solid basins, constructed from cement with more control settings to measure and regulate the heating, which makes them more reliable and more operable. As a result, the output seems to have substantially increased per refinery.

Below is a compilation from a video featuring such a semi-professional refinery in Tel Rifaat, north of Aleppo, in 2017.

Tel Rifaat, 2017

The refinery above was was build in 2017, but likely abandoned after Operation Olive Branch, the Turkish-led incursion into the Afrin region of Syria in 2018. Geo-located by @obretix

Semi-professional refinery, Tel Rifaat

Cradles Of Informal Oil Refining

The use of makeshift refining outside Deir ez Zor would logically make sense to appear slowly to move westwards, as knowledge of this practice is spread by displaced refinery workers. Therefore, we initially started in Raqqa governorate, where we looked for refineries on satellite imagery. The first imagery available in this region is from October 2013, showing artisanal oil refineries close to the M4 road from Raqqa to Manbij. The black spots at the end of the water ditch show oil waste on the soil, indicating the refinery has been recently active. In the same location, in 2016, we see that this has largely disappeared, meaning they aren’t active anymore.

Makeshift oil cluster, west-Raqqa, 2013-2016

The first visual confirmation, via satellite imagery, of informal refining on the west bank of the Euphrates river in Aleppo is from 2016. But the first media reports about this trend already appeared in 2013, showing [archived] roadside refining in Aleppo governorate, as well as here at Manbij, as civilians struggled to get access to affordable gasoline. Other reports also indicated that refineries were operational in Tel Rifaat, north of Aleppo city, where we found some roadside burners in 2013/2014, south east of the town.

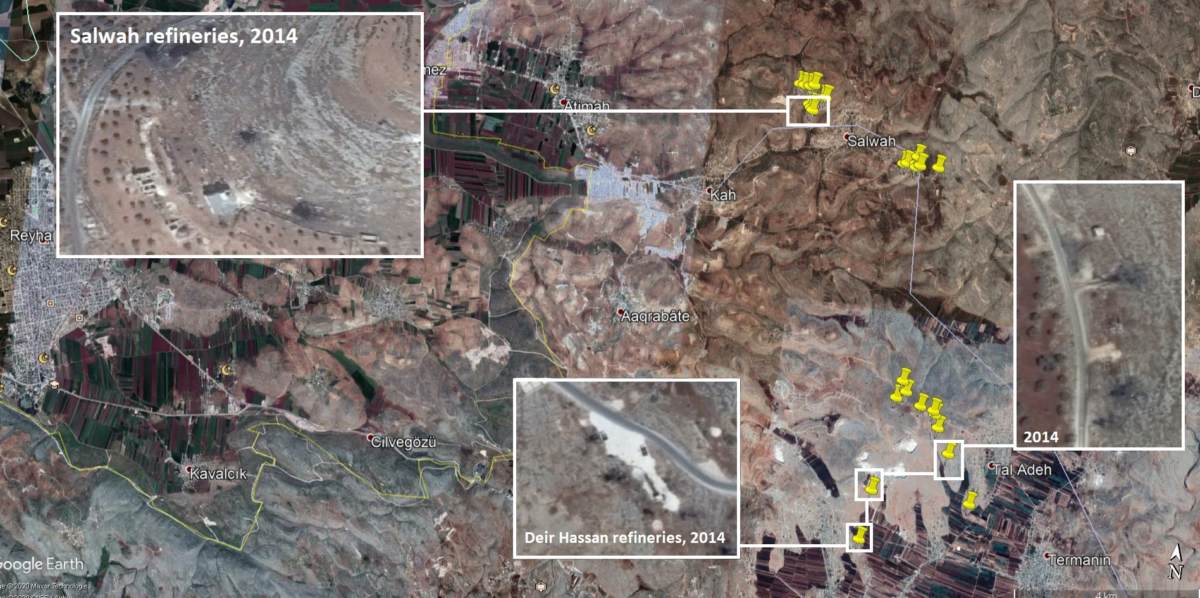

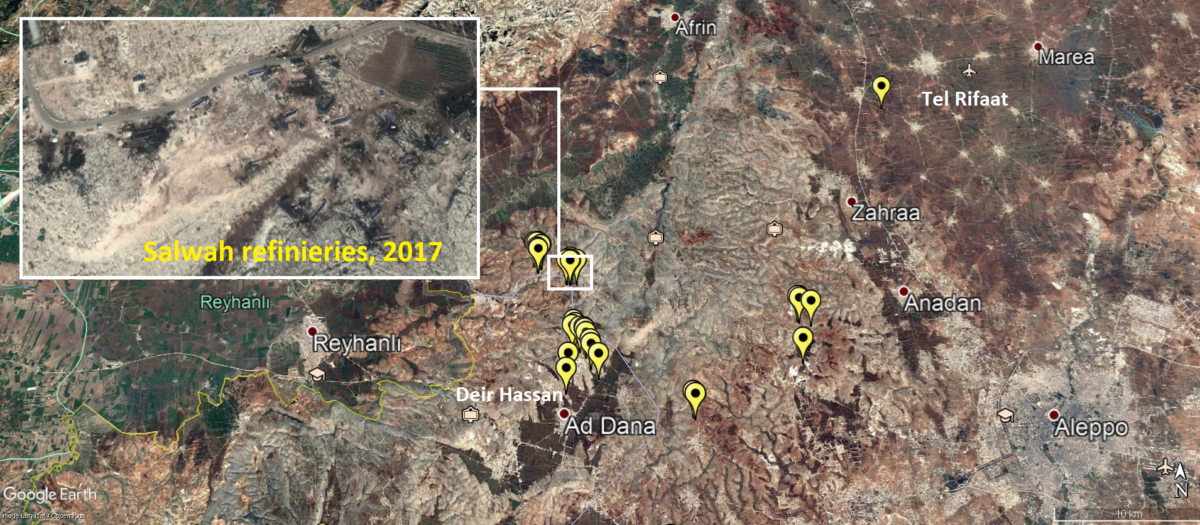

According to this interview with an oil worker in an Al Jazeera article from 2013, the use of “primitive burners” started in 2013 in Deir Hassan, a tiny village in Idlib governorate on the border with Turkey. Using Google Earth Pro, we indeed found 1 refinery east of the village in 2013, and more in 2014. Roughly 8 kilometers north of the village, in the town of Salwah, a handful of artisanal refineries also showed up on 2014 imagery, while in the hills between, larger types of refineries appeared on the roadside in 2017.

Crade of artisanal oil refining, Deir Hassan/Salwah, 2014

From Jarablus To Jisr Ash-Shugur

Informal refining became a common practice throughout north west Syria in the period of 2013-2020, with local petrol entrepreneurs quickly learning how to improve the technology and boost output at these refineries. In the beginning, through 2013-2015, one could find a handful of low quality refineries near villages, but that changed after 2016, when we saw a rapid increase in various parts of the country. Post 2016, these refineries can often be found in smaller and larger clusters, as this likely makes it easier for transportation with large tanker trucks to deliver crude oil and export the refined version to the final destination.

In the next section, we will look at specific areas, the local dynamics of refining, and the living and working conditions at these locations.

Eastern Aleppo Governorate

The area between the Euphrates and the Sajur river became a hot spot of the local informal oil industry. In this part of northern Aleppo, we have identified 30 clusters with at least 400 refineries that are or have been used through the period 2014-2020.

Al Kusa Refineries

On the west bank of the Euphates, small pockets of refineries with large burners, and, further away, a large cluster, appeared in the first weeks of January 2017, as can be seen on Sentinel-2 imagery. By March 2017, the location quicklyl expanded, with roughly 60 refineries, but a few months later this number dropped again, with only a handful operational. By 2018, the location seemed to be completely abandoned.

Al Kusa refineries comparison

Yet in June 2019, the area was cleared and an IDP camp was constructed on the former oil refinery site. It is not clear if proper remediation of the soil took place before building the homes for displaced Syrians at this location

makeshift oil refining site turned into housing project for IDP south of Jarabulus https://t.co/sVJpSXOVTi pic.twitter.com/ugvrjFX8YO

— Samir (@obretix) April 17, 2020

Nearby, a smaller cluster of refineries was still operational as a fire broke out in August 2019 at one of the sites at Bir Al Kussa, and the White Helmets were dispatched to take it out.

This Al Jazeera interview from 2017 provides background information on the refining process, as explained by one of the local workers at the location north of the Sajur river.

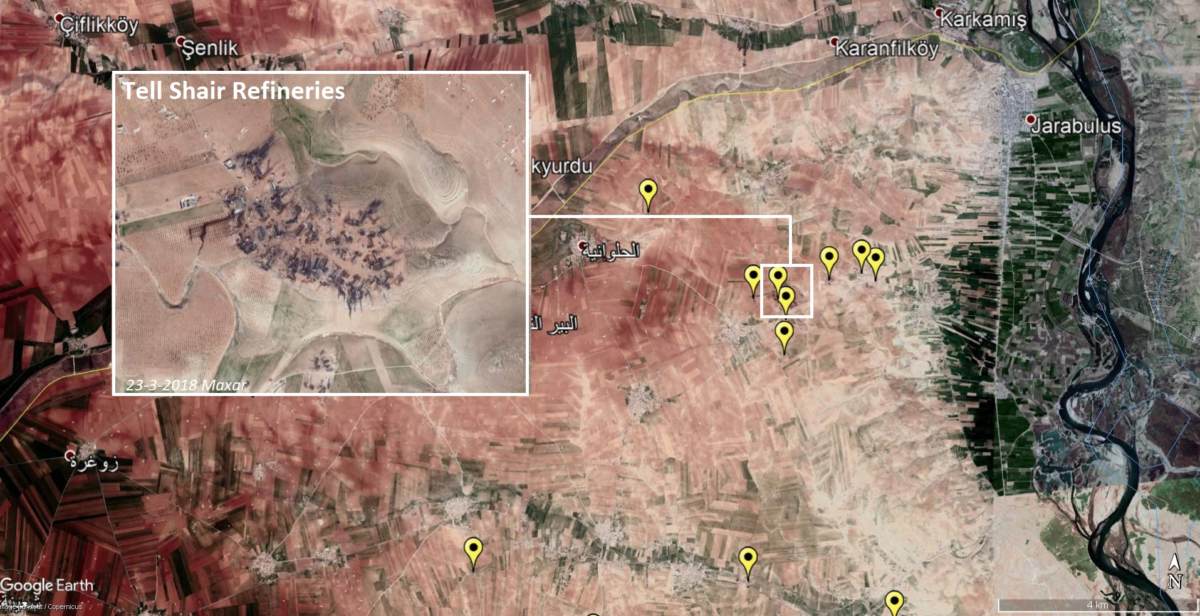

Tall Shair Refineries

Just over 5 kilometers southwest of Jarabulus city, more clusters of refineries started to appear at the end of 2016 — and these rapidly grew in 2017. Various media reports were produced at this location in 2016, showing interviews with workers at different locations. The White Helmets’ fire brigade became a frequent visitor to this area due to numerous fires that broke out.

White Helmets firefighter teams managed to extinguish a huge fires that broke out in an oil refinery in #TellChair town near #Jarabulus city in #Aleppo countryside, and controlled the situation without casualties. pic.twitter.com/jAlUG0NvkL

— The White Helmets (@SyriaCivilDef) June 2, 2018

The increase of artisinal #oil refining throughout #Syria also comes with additional health and environmental risks, as this example of a burned down refinery shows https://t.co/u7HEv2S6HM

— Wim Zwijnenburg (@wammezz) June 24, 2019

Tell Shair clusters: Over 100 refineries, both active and inactive, have been counted at around 8 clusters near Jarablus

What also became clear in the aftermath of the killing of the leader of the so-called Islamic State, Bakr Al Baghdadi, who was hiding in Idlib on the border with Turkey, is that the oil trading routes were frequently used to smuggle ISIS operatives through SDF and rebel controlled areas. ISIS used to have a foothold in Idblib and Aleppo, before being defeated by rival factions.

On October 27, it was reported that a U.S. airstrike targeted an oil tanker on the road between Mazlah and Youssif Bik, a few kilometres south of the Tall Shair refineries. Soon, it turned out that the strike killed Abu Al-Hassan al-Muhajiir, the spokesman of ISIS. Apparently, oil trucks with hidden compartments were frequently used to smuggle individuals out of Deir ez Zor to Idlib and Aleppo.

Footage of a 'burning tanker' which may corroborate #SDF claims of targeting #IslamicState spokesman Abu Al-Hassan al-Muhajiir.@AleppoAMC confirmed a 'rocket attack' against Ain al-Bayda, same village mentioned in Mazloum's most recent tweet. https://t.co/5bbkWYnGx1

— Riam Dalati (@Dalatrm) October 27, 2019

The oil industry also became a target for Russia and Syria. The same area was bombed on November 25, 2019 by the Syrian Air force, it was claimed online, though this nighttime air strike was likely done with Russian support. This was part of a wider attack on informal oil refineries in Aleppo, and there was also bombing of a large cluster in Tarahin, north east of Al Bab.

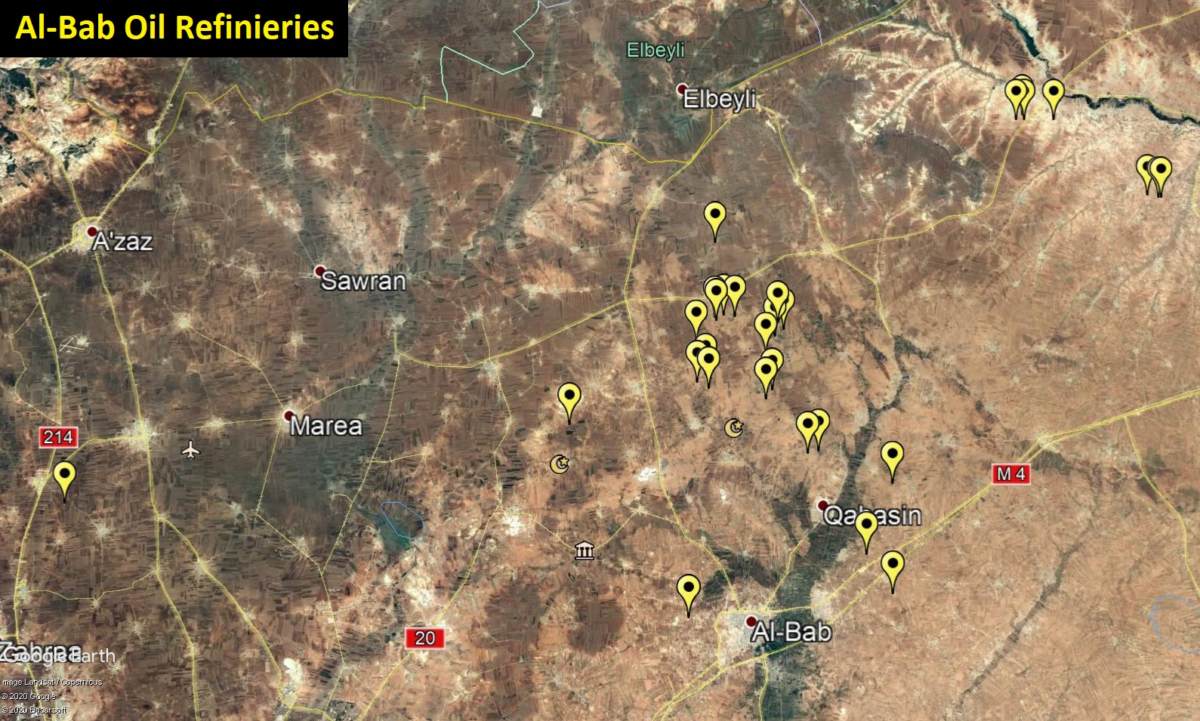

Air Strikes And Explosions: A Hazardous Trade In Al-Bab

When we followed the road from Jarablus westwards, crossing the Sajur into Aleppo province, a couple of smaller clusters were found along the roadside. It’s not until we reached the countryside north of Al Bab where the real action started. There were already some roadside burners active near Al Bab since 2013, according to this video, but we had not been able to confirm the location. Other small clusters with over a dozen refineries have been popped up around 2015/2016, but it wasn’t till the summer of 2017 when this area became a key oil production site.

Tahrin Refineries

Three main clusters are located close to each other north of the village of Tahrin, or also known as Tarahin. The oil production and concerns from civilians and workers at these sites have been very well documented in local news reports. Using Sentinel Hubs EO Browser, we made a timelapse showing the rapid growth of oil refineries at this location between May 2017 and May 2018.

Sentinel-2 Timelapse, 2017-2018. Colour Infrared.

This location appeared on our radar in June 2018, when a posting appeared online in which a Twitter user made notice of how displaced Syrians in a nearby camp started complaining about the health effects of the smoke. Dozens of young children were allegedly hospitalized due to respiratory problems from continued exposure to the noxious fumes at the displacement camp site.

Reports coming in from children in IDP camps suffering from health problems related to exposure toxic smoke from makeshift #oil refineries north of Al-Bab, #syriahttps://t.co/aMFNgxkmgWhttps://t.co/NTjVWa9bME pic.twitter.com/RnKqGsH9mu

— Wim Zwijnenburg (@wammezz) June 6, 2018

On satellite imagery from 2018, a substantial amount of tents and campsites is clearly visible, set up in the orchard around the refineries.

Displaced people living in orchards near oil refineries

Still from a 2019 news report by Orient TV at the Tahrin refineries

Orient TV at Taharin, 2019.

In this video, from likely the same location in 2019, health problems are also mentioned as a serious concern among local workers and citizens. Risks also came from frequent fires — as happened at Taharin in June 2019, seen in this White Helmets video — and explosions from the crude oil cooking barrels

Here is a horizontal verion of the video showing the explosion and large smoke plume. Still waiting for satellite images of June 13 to confirm pic.twitter.com/7NrvsPPtjz

— Wim Zwijnenburg (@wammezz) June 13, 2019

Another interesting thing we learned from the videos had to do with the use of the burned crude oil waste as cooking coals. After the crude oil is heated and the benzine/gasoline/diesel has been collected, the tar remnants are scrapped from inside the large barrels, often by children/teenagers, as they fit inside the barrels. This exposes young people to the noxious vapours inside, explaining the large amount of respiratory diseases and skin problems from anecdotal reports. The “tar coals” they collect from inside, as well as the “oil sands” from outside the barrels were spills occurred, are reused again as sort of cooking materials

Steps News Agency at Taharin 2019

Stills from a 2019 video by Step News Agency at Taharin show how the process of coal production from oil waste scrapped from the oil drums, which is then used for heating.

Air Strikes Against Refineries

On November 25, 2019, this location was one of the three main targets in an air strike carried out by the Syrian Air Force and/or Russian Air Force, with the other targets being Jarablus and Al Kousa

#BREAKING NEWS video#US led coalition targeted #ISIS oil tankers & small oil fields between Al Bab & Jarabulus in northern #Syria #ISIL is smuggling oil & selling to #Turkey,every night at 11 pm until 5 am

Turkish gov Cooperation with #Islamicstate continues#جرابلس #الباب pic.twitter.com/93iHFT7Ewy— Botin Kurdistani (@kurdistannews24) November 26, 2019

Videos appeared the day after, showing one of the bombed locations with burned out oil storage tankers. It was geo-located to Tahrin by Twitter user @obretix

geolocation of last night's airstrike on makeshift refineries near Tarhin https://t.co/PKQBwdiGlA pic.twitter.com/GKef0EDSWW

— Samir (@obretix) November 26, 2019

The bombing of the refinery and supply routes apparently had an effect, as according to this video from City Al Babs News, shot at the location in February 2020, the refineries were taken out of business as crude oil was no longer delivered to Taharin. However, in a video posted in April 2020 by the White Helmets, when a fire broke out a roadside cluster of refineries south east of Tahrin, near the village of Susanbat, indicating that there was still some access to crude oil for refining

A huge fire was extinguished by the firefighter teams in the White Helmets after it broke out in one of the primitive fuel refining stations in #Sosnbat village east of #Aleppo this afternoon. Our teams managed to control the fire without recording casualties. pic.twitter.com/gYu6IcSe2o

— The White Helmets (@SyriaCivilDef) April 13, 2020

Other Al Bab Refineries

Apart from the major Tahrin cluster, the area around Al Bab has over a dozen of smaller clusters of refineries. Some of them were also bombed by Russia, such as this one at Kabr Makri when, 8 civilians were alleged to have been killed and dozens more alleged to be wounded.

غارة جوية في قرية قبر مقري بالقرب من مدينة #الباب شرقي #حلب استهدفت محطة محلية لتكرير النفط يديرها أحد أبناء المنطقة pic.twitter.com/ERiADL9bW0

— Aleppo24 (@24Aleppo) December 23, 2015

There was another bombing in 2016, again by the Russian Air Force, of which the Russian Ministry of Defense rreleased video footage which was geolocated by @obretix to be at the Kabr Makri refineries

RuAF airstrike on a makeshift oil refinery https://t.co/30UpebwTLr (19 Jan 2016) geolocated ~8km east of al-Bab https://t.co/3Y5OwHM6zu pic.twitter.com/bTCkFyyqoD

— Samir (@obretix) February 21, 2017

Other videos we have not been able to geolocate also show various incidents with refineries at sites around Al Bab, such as this video of large fire from 2017 and an explosion at a refinery in September 2019. Below an overview of all the clusters of refineries located.

Clusters of oil refineries around Al-Bab, Aleppo

Oil Production Around Aleppo And Idlib

As mentioned in the beginning, informal oil refining had already begun in 2013, between the Turkish border and Aleppo city around the towns of Deir Hassan and Salwah, in the northern part of Idlib.

According a 2019 interview with an owner of a cluster of refineries, there are 450 refineries in this area where crude oil is shipped to — it is either refined there, or shipped to Turkey, as stated in an interview with a local merchant from 2013.

In 2015, construction began on a handful refineries in the hills west of Aleppo city, while more refineries appeared in 2016 in the same areas where this practice started, namely near Salwah on the Turkish border. In 2017, a handful of makeshift roadside refineries appeared near Tal Adeh in the south of this area. According to this White Helmets video, a refinery west of Aleppo in the village of Al Houta was bombed in 2017 by Russian airplanes, and various incidents were reported with transportation of oil.

There are also incidental reports of accidents with oil refineries in the Kurdish- controlled area of Tel Rifaat.

Clusters of oil refineries west of Aleppo

Further down on the border between the two governorates, various large clusters can be found and their use has been well documented.

As one worker described it during an interview with Irfaa Sawtak, “Hand refineries are located in the Idlib countryside, at a rate of one to three in every village or city”. This statement is not far from the truth, going by the available satellite imagery that shows that some locations indeed have at least one refinery at every village.

As with other locations, environmental health risks are rampant, as a local doctor explained in this NRT video [archived] from Idlib in 2017, and other discussions over the health concerns were raised in this Halab TV broadcast on oil refineries in Idlb from 2017, as well as this Al Jazeera Arabic interview at one the location in Idlib, also in 2017.

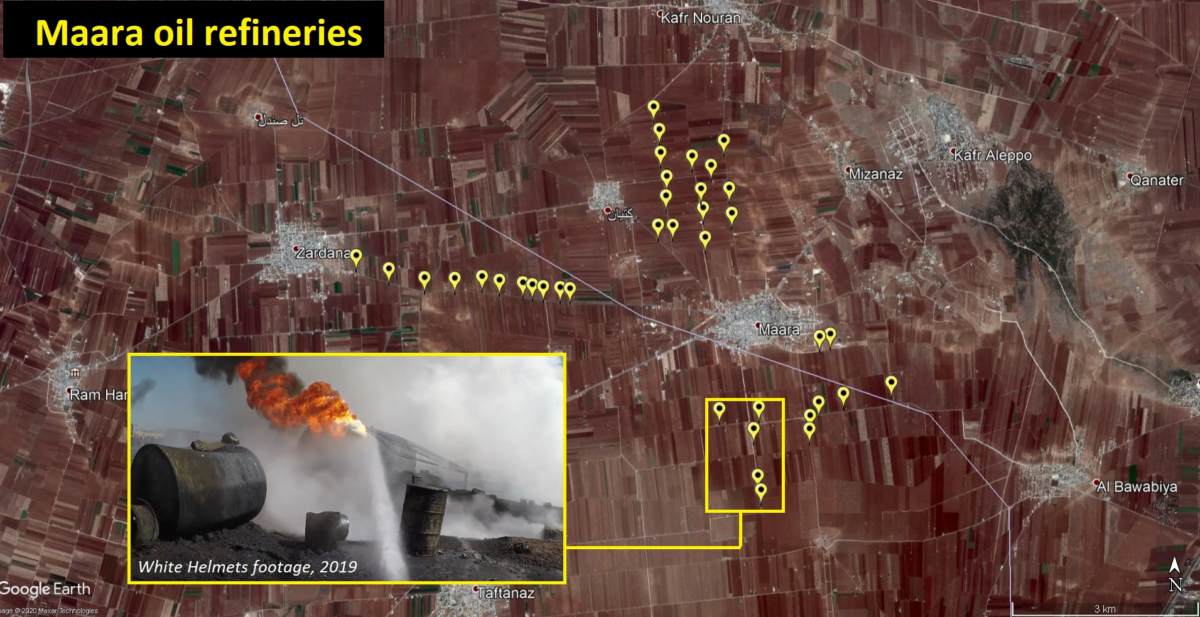

Maara Refineries

There are particularly large clusters around the town of Maara, which is often visited by the media, while documentation from the White Helmets shows that incidents regularly take place at the refineries on the roads around this town.

Clusters of oil refinieries around Maara, on the border between Idlib and Aleppo

Sinjar Refineries

Only 15 kilometres southwest of Maara, close to the city of Saraqib, a similar pattern of refineries, spread around various villages, can be found. The majority of these refineries seem to have been constructed and operational throughout 2017, as the most recent satellite imagery from 2018 on Google Earth shows most of them as abandoned. This area was also subject of this article published in 2016, where a local refiner claimed that there are over 3300 refineries in the “liberated areas of Syria.” This area was taken over by the regime in 2018, explaining why they went out of service, as local populations fled and/or had access to refined oil from regime sources.

Clusters of oil refineries around Sinjar, Aleppo, 2017.

Similar constructions with various clusters around villages were also in operation in 2017/2018 on the road southward from Abu Adh Dhuru, leading to the town of Karayya, where multiple clusters are visible as well. Some of the refineries close to Abu Ad Dhura were allegedly also targeted by Russian warplanes in 2016

استهداف الطيران السوري مصافي لتكرير النفط في منطقة ابو الظهور في ريف ادلب الشرقي pic.twitter.com/HsLsCqRUH2

— The Syrian Arab Army (@Syrianarmyxx) February 15, 2017

The clusters at Karayya were also bombed in 2017, according to this Step news video footage that mentioned the nearby town of Sinjar in Idlib.

Clusters of oil refineries around Karayya, 2017

Through parts of Idlib and Aleppo, smaller clusters can be found as well — at roadsides and villages, or else we spotted single refineries in backyards for domestic use, including in villages in Al Fuhayl, in the rocky hills of Kafr Nabl, and in the countryside east of Khan Assubul. These are all locations we happened to come across, but there are likely hundreds and hundreds of more locations where these toxic refineries once or still form the backbone of the much needed energy production used by civilians. Cooking fuels, transportation, and heating are all essential uses in the harsh wartime conditions.

From The Barrel To The Grave.

Summing up our findings, oil trade and refining has quickly spread throughout Syria after professional production collapsed in the wake of the conflict.

In non-regime controlled areas in particular, civilians struggled with access to fuel for cooking, transportation, and heating, and artisanal refineries quickly started spreading as a coping strategy. Oil smugglers, criminal gangs, and armed groups increasingly profited from the export of crude oil from the oil fields in eastern Syria to rebel-held Idlib and Aleppo, where local workers and displaced civilians build and operated refineries.

These backyard burners and cluster refining practices also came with an additional health impact for civilians already bearing the brunt of the bloody war.

Working day in and out, surrounded by the noxious fumes of burning oil, rubber and refined petrol, thousands of people, including many children, suffered from acute serious respiratory problems, skin problems, and infected wounds, while those with prolonged exposure could suffer from internal organ damage through accumulation of toxins in the body.

In total, we identified at least 300 clusters of makeshift oil refineries in the period of 2013-2018. At each cluster, there is at least 1 refinery, though we found clusters with 50 refineries as well.

For example, at Maara in Idlib, we placed roughly 40 points, and counted 150 refineries. So taking 5 refineries per points as a minimum gives us a total of at least 1500 refineries as the lower estimate. Given the fact that at some locations there are substantially more refineries, and the fact that we very likely missed many refineries due to outdated or absent imagery, a more accurate estimate is likely to be around 5000 refineries.

This estimate covers all refineries that have been built, though it should be noted that not all have been used at the same time. In some locations, we witnessed the construction and later abandonment of these refineries, most of the times associated with recapture of the area by regime troops, due to targeting by airstrikes or other military activities, or else due to reasons unknown.

With the large number of refineries that once were or still are operational, this means thousands of civilians, including many children and teenagers, have seen prolonged exposure to hazardous substances and noxious fumes, which could have long-term health complications.

Numerous incidents have been reported of people dying from exploding barrels but also casualties from airstrikes against these oil targets by Russian and Syrian warplanes. We still have to arrive at a better understanding of how the local environment is affected by the oil waste products that polluted local water sources and soils, as this could seriously hamper post-conflict living and working conditions for local communities.

Proper documentation of this type of conflict pollution is needed to minimize the health and environmental risks to civilians. We have demonstrated that a head start can be made with open-source investigation and the use of remote sensing to identify both the specific locations and the magnitude of this phenomenon.

The findings should spur inclusion of these risks in humanitarian and medical response policies, and, at a later stage, in post-conflict remediation and reconstruction efforts, as was also recommended by UN Environmental Assembly resolutions and recent informal debates in the UN Security Council on environment, peace and security.

This article could not have been written without the valuable help of Samir @obretix who provided information air strikes, transport routes and geo-locations of refineries, to Noor Nahas @NoorNahas1 for video footage and translation, to Maha Yassin @MahaalGhareeb for translation and Yifang Shi for QGIS support