How to Mainstream Neo-Nazis: A lesson from Ukraine’s C14 and an Estonian think tank

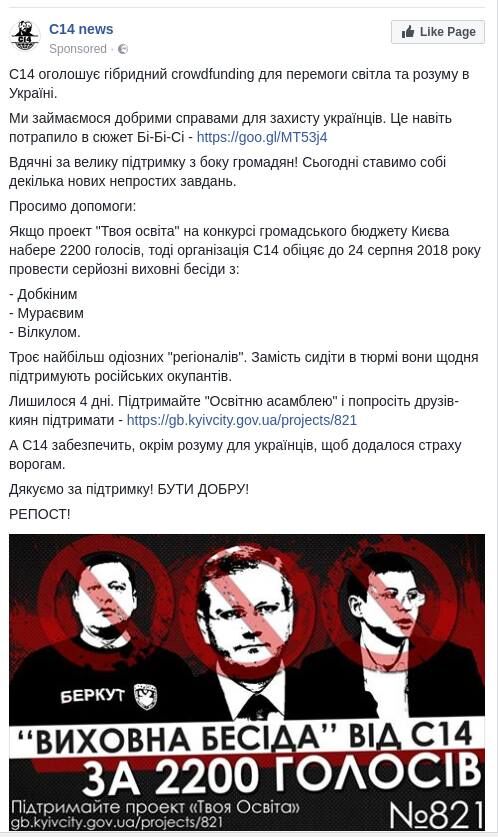

Ukraine’s Education Assembly (Освітня асамблея) is officially registered (archived copy) as a “community organization” in Ukraine. On its face, nothing about how they describe themselves sounds particularly worrisome, as seen in the group’s description of itself on their website:

“Education Assembly is a project whose goal is comprehensive youth development (…) The project takes the form of lectures and seminars, held in a cozy and friendly atmosphere. Here we have the best speakers, willing to share their knowledge and experience across a variety of fields. The initiators of Education Assembly are active youth who are aware of the importance of knowledge in the contemporary world and strive to make this knowledge accessible to all.”

Take even a slightly more focused glance at the organization, though, and things will start to look different.

You’ll probably notice that Education Assembly’s logo resembles that of a Ukrainian neo-Nazi group, C14. The lower half of Education Assembly’s logo, a black-and-white globe, is exactly the same as C14’s, as are the black bars above the globe where Education Assembly’s name is written.

A comparison of Education Assembly and C14’s logos, from Estonian news site Delfi.

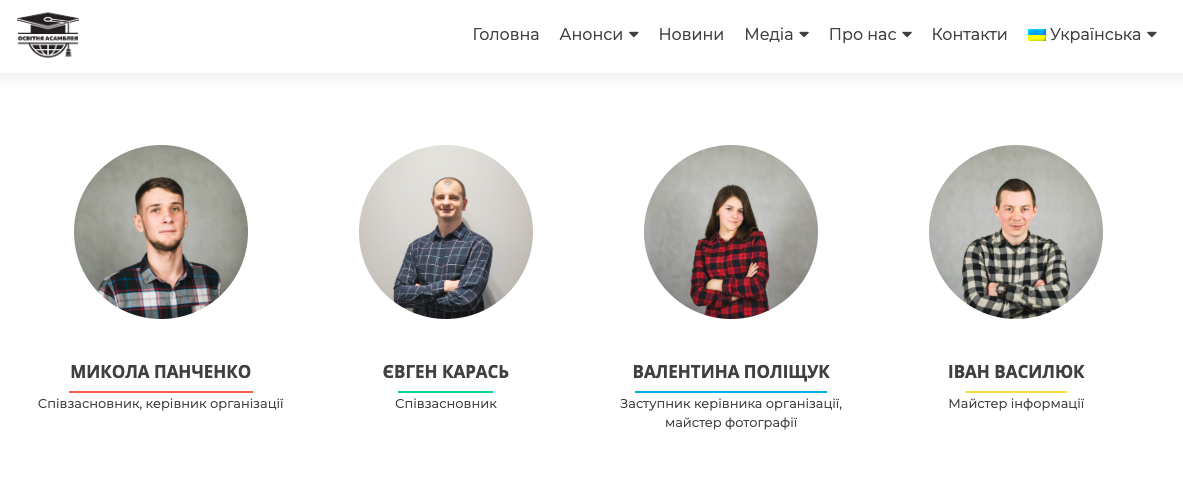

You’ll likely find out that one of Education Assembly’s co-founders, Yevhen Karas, is actually the notorious leader of C14, a group that’s been identified as neo-Nazi by former members and experts of extremism — and a group that earned international headlines for instigating a pogrom against a Roma camp in 2018.

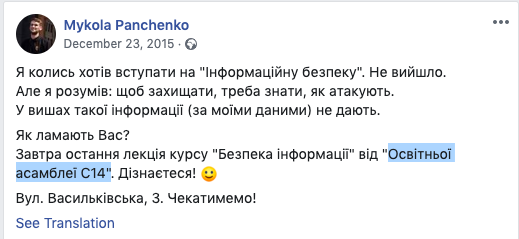

You’ll also see that their other co-founder, Mykola Panchenko, is also a member of C14. You’ll surely find photos from Education Assembly’s office in central Kyiv, where a larger logo of theirs is visible in social media posts; the logo’s outer edges resemble a sonnenrad, a well-known symbol used by neo-Nazis and far-right extremists the world over, including the Christchurch shooter.

Despite all these red flags, Education Assembly has still had success in working its way into the mainstream in Ukraine and beyond. As revealed in our previous investigation, a leading Estonian think-tank, the International Center for Defense and Security (ICDS), worked alongside Education Assembly at a “summer school” in 2018, apparently unaware of the fact that Education Assembly is a C14 organization.

And just months after they first worked alongside Education Assembly, the leading Estonian think-tank welcomed one of Education Assembly’s co-founders to an event in Tallinn.

A photo from ICDS of Estonian president Kersti Kaljulaid speaking at the International Autumn School Resilience League 2018 in Tallinn, Estonia.

It’s an unfortunate, but obvious, example of how far-right and outright neo-Nazi movements, in Ukraine and beyond, can infiltrate and work their way into the mainstream — even to the point of meeting an EU country’s president at an event supported by NATO and German taxpayers.

The “Resilience League” and its “autumn school” in Estonia

In November 2018, ICDS welcomed the head of C14’s Education Assembly, Mykola Panchenko, to an event in the Estonian capital. But according to the organization’s own comments to Bellingcat, this came months after ICDS became aware of Education Assembly’s links to Yevhen Karas and C14.

In emailed comments, a spokesperson for ICDS told Bellingcat that “Dmitri Teperik, Chief Executive of ICDS found out that Yevhen Karas is co-founder of the Education Assembly and leader of the C14 at the summer school in August 2018.”

But if ICDS was indeed aware of Karas and C14’s links to Education Assembly in August 2018, their decision to welcome Education Assembly’s other co-founder and head to an event in Tallinn three months later is an odd one.

It was no fringe event. The “International Autumn School Resilience League 2018” was, according to ICDS, supported by NATO and the German Embassy in Estonia. It was also supported by Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Baltic States, the German foundation linked to Germany’s Social Democratic Party (SPD) that, like other German foundations attached to political parties, is funded by German taxpayers. The event also featured the president of Estonia, Kersti Kaljulaid.

A photo from Education Assembly’s Facebook page showing an unidentified speaker at the International Autumn School Resilience League 2018 and a banner from School supporter Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung.

“It is regrettable that we were not aware of the link between the Education Assembly and a far right movement,” ICDS’s spokesperson told Bellingcat.

But, as we’ve shown above, Education Assembly’s links to C14 aren’t hard to find. Basic due diligence would have shown not only Education Assembly and C14’s obvious relationship, but also Mykola Panchenko’s publicly documented links to C14 well before he was welcomed at the November 2018 event in Estonia.

“Our partners” in Estonia, according to C14’s Education assembly

According to ICDS’ webpage, the “International Autumn School Resilience League 2018 on Cognitive Resilience and Strategic Communication” was co-hosted by themselves and NCDSA in Tallinn, Estonia in November 2018. The event, according to ICDS, featured “speakers, trainers, knowledgeable specialists and recognised practitioners” from a number of European countries, including Estonian president Kersti Kaljulaid.

But it also featured the head of C14-linked Education Assembly, Mykola Panchenko. In a Facebook post in March 2019, Panchenko posted about having attended the event in November 2018 in Estonia. Further, a post on Education Assembly’s Facebook on November 13, 2018 confirms that a member — Panchenko, as evidenced by a comment underneath the post — was indeed present in Estonia at the event.

“Last year we visited our partners,” Panchenko wrote “at [ICDS and NCDSA’s] International Autumn School for Information Security Resilience League in Estonia.” In the post Panchenko even made reference to an apparent conversation he had at the event with Estonian president Kaljulaid.

Panchenko ended the post by thanking ICDS and NCDSA for the “invitation” and that “we look forward to future cooperation.”

Photos accompanying Panchenko’s post show him present at the event and posing for a photo with ICDS member Grigori Senkiv (also the director of the NCDSA) and ICDS Chief Executive Dmitri Teperik.

Education Assembly head Mykola Panchenko with ICDS member Grigori Senkiv (also the director of the NCDSA) and ICDS Chief Executive Dmitri Teperik (Facebook)

“Education Assembly” — or what was once “Education Assembly C14”

In response to our previous investigation, ICDS claimed in Estonian media to be unaware of Education Assembly’s associations with C14 when they appeared alongside Education Assembly’s Panchenko and Yevhen Karas in August 2018.

But it’s not difficult to establish, through simple online searches and scrolling through social media profiles of the organizations, that Education Assembly has long been associated with C14. Basic due diligence would have flagged this association to ICDS and others, especially since, as ICDS’ spokesperson told Bellingcat, it was Education Assembly and another Ukrainian group, the Center for Progressive Communications, who approached ICDS looking to cooperate. (“We did not seek out Education Assembly and they were not suggested to us,” Bellingcat was told).

Ukrainian researcher of the far-right Anya Hrytsenko noted in a 2017 article that Education Assembly and C14 were linked, bluntly referring to Education Assembly as “a project of neo-Nazi organization C14”, and linking to a screenshot of an undated Facebook post from C14 where they urged support for their then-new initiative, “Education Assembly.”

but An undated screenshot of a C14 Facebook post urging followers to support a then-new project of theirs, Education Assembly.

The connections to C14 and Yevhen Karas were obvious then: Karas is one of the legal co-founders of Education Assembly, per public records; Karas is also listed on Education Assembly’s own website homepage as a “Співзасновник” — co-founder — and has also has given Education Assembly seminars that have been publicly advertised.

A screenshot of Education Assembly’s website main page showing Yevhen Karas listed as a co-founder of the organization.

Moreover, as Estonian media outlet Delfi made clear in its article interviewing ICDS’ Teperik on August 2, the logos of C14 and Education Assembly are noticeably similar.

As if this wasn’t clear enough, in 2015 and 2016 the group even openly referred to itself as “Education Assembly C14.”

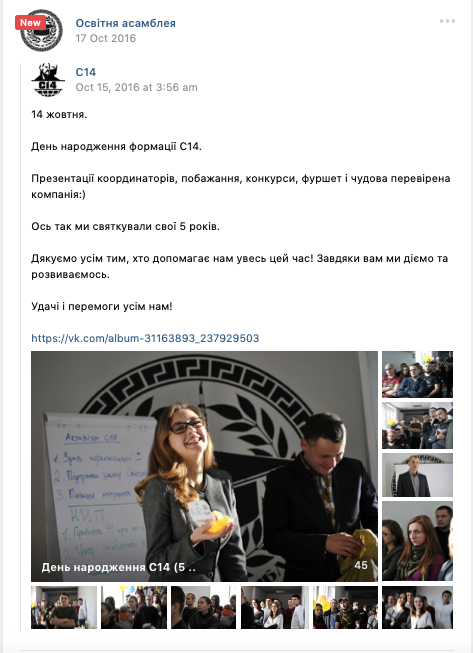

In addition, Education Assembly’s VKontakte page from October 2016 — just months before the Russian social media network was banned in Ukraine — reshared a post from C14 celebrating the fifth anniversary of their founding. They were celebrating in what is clearly identifiable as Education Assembly’s office.

C14’s five-year-anniversary celebrations in 2016 at Education Assembly’s office. Education Assembly’s logo on the rear wall, on its outer edges, resembles a sonnenrad, a well-known symbol used by neo-Nazis and other far-right extremists.

Taking the extreme to the mainstream

As we wrote in our previous investigation, C14’s reputation for violence and extremism is well-documented. Andriy Medvedko and Denys Polishchuk, two C14 members, are currently on trial for the 2015 murder of Ukrainian reporter Oles Buzyna (both deny the charges). Moreover, despite their name evoking the neo-Nazi ’14 words’ slogan and referred to as a “neo-Nazi” organization by former members and several experts on extremism, they deny being a neo-Nazi organization. In 2018 they sued a Ukrainian media outlet for referring to them as neo-Nazis on Twitter — a case in which, just this week, a Ukrainian court inexplicably ruled in C14’s favour.

Despite this — and despite Education Assembly’s open links to C14 — the organization has managed to find mainstream fans and friends in Ukraine and be treated as a normal, mainstream civic organization.

For one, C14 and other far-right organizations receive funding from the Ukrainian state. The Department for National Patriotic Education in Ukraine’s Ministry of Youth and Sports, as we revealed in our recent investigation, is funding Education Assembly’s “summer school” in August 2019.

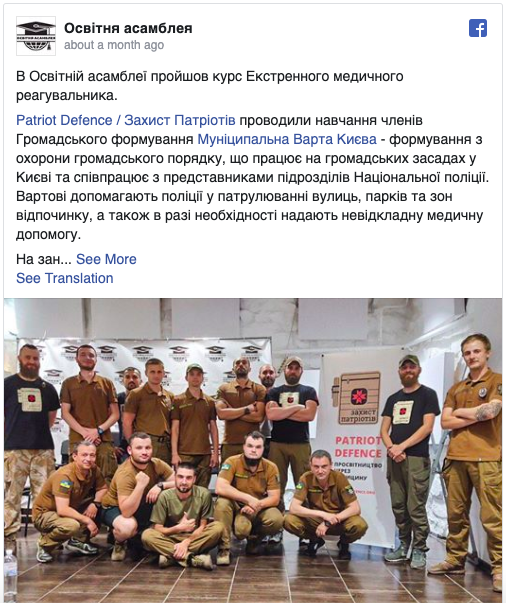

Furthermore, on July 29, 2019, Education Assembly hosted a lecture by the Kyiv branch of the European Students’ Forum (AEGEE), which bills itself as “one of Europe’s biggest interdisciplinary student organisations.” In June 2019 Education Assembly hosted a training session at its offices by Patriot Defence, an NGO focused on medical trauma care founded by Ulana Suprun, Ukraine’s current health minister; Suprun herself has a history of making statements supportive of C14 and appearing in photos alongside C14 members.

Education Assembly’s office have also, over the last few months, played host to another NGO’s first-aid training seminars and also hosted a strategic communications consultancy to speak about NGO, government and business cooperation.

There are many other examples of high-profile members of Ukrainian politics and society who have appeared at C14’s Education Assembly, showing just how deep the group has crept into Ukraine’s mainstream. Journalists, including from US-state funded RFE/RL, and even a member of Ukraine’s parliament have given seminars and lectures at Education Assembly.

An event advertised at C14’s Education Assembly featuring a number of journalists from mainstream Ukrainian news outlets.

The evening of August 8, Education Assembly hosted a session on “how to act in case of search, arrest and interrogation,” led by lawyer Viktor Moroz — the lawyer who defended C14 in their lawsuit against Hromadske. Groups that Education Assembly claims supported the event are the “National Centre for Human Rights,” a C14-linked organization that features the accused murderers of Oles Buzyna as its co-owners (Andriy Medvedko and Denys Polishchuk), as well as the public communications department of the Kyiv city administration.

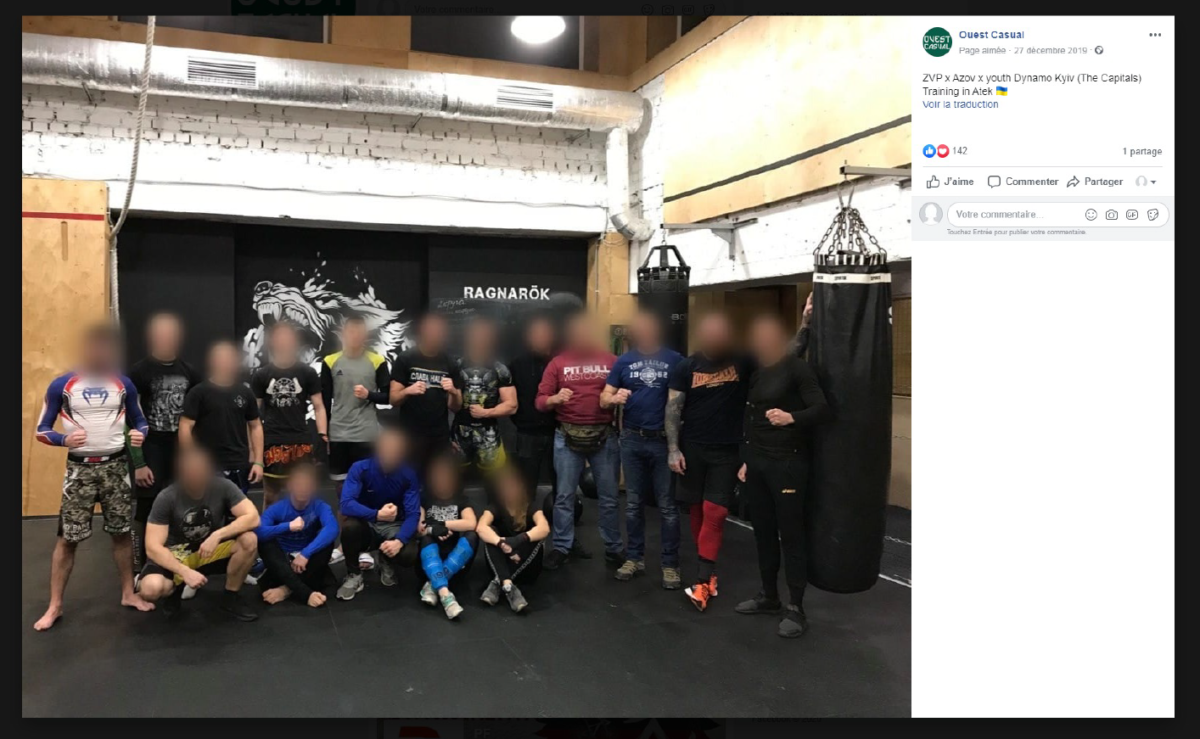

But C14 is hardly the only group on Ukraine’s far-right to have had success trying to insert itself into and infiltrate the political mainstream. The Azov movement, Ukraine’s largest and most ambitious far-right group, might be the best example. With everything from sympathetic supermarket magazines giving their movement constant cover stories, Ukrainian broadcasters airing puff pieces denying the movement’s far-right, far-right affiliations and even owning a fancy sports bar near Kyiv’s central railway station, the Azov movement — even if it can’t come close to victory at the ballot box — has worked its way into Ukraine’s mainstream. A leading member of the Azov movement, Olena Semenyaka, even appeared at an official Ukrainian embassy event in Riga, Latvia in 2018.

Azov’s Olena Semenyaka, “international secretary” of the National Corps, Azov’s political wing, speaking at the Ukrainian embassy in Latvia in 2018

Other far-right groups in Ukraine can tell similar stories, even if they lack Azov’s size and strength. For example, Tradition and Order, a small far-right anti-LGBT movement who tried to spearhead protests against KyivPride, has made friends with Ukraine’s powerful Orthodox Church; the group’s leaders even receiving medals from church officials recently.

In these and other examples from Ukraine, far-right groups make superficial efforts to mask their histories, moderating their rhetoric and language and positioning themselves as ‘defenders of Ukraine’ against Russia. These groups, including C14, Azov and others, tend to deny that they are neo-Nazis (e.g., suing media outlets, denying their symbols have Nazi origins, etc.) or extremists; they downplay their more violent and hateful actions and rhetoric and sometimes outright dismiss legitimate criticism as Kremlin propaganda. The result is at least part of the mainstream takes their well-crafted public images seriously, whether they do so willingly or through ignorance.

Panchenko: “a representative of the C14 organization”

ICDS appeared to take Education Assembly seriously, even though it’s not difficult to establish that co-founder Mykola Panchenko has a long history with C14. Still, he was able to be welcomed to Estonia by ICDS and NCDSA in November 2018.

There are indications, publicly available, that Panchenko sympathized with the violence of the C14-affiliated “Knights of the City” group that we in our recent investigation referred to as being “involved with incidents of violence aimed at those it deemed to be addicts or alcoholics…” Panchenko shared a post in 2018 praising Knights of the City that “we will beat…without warning” individuals who set off firecrackers.

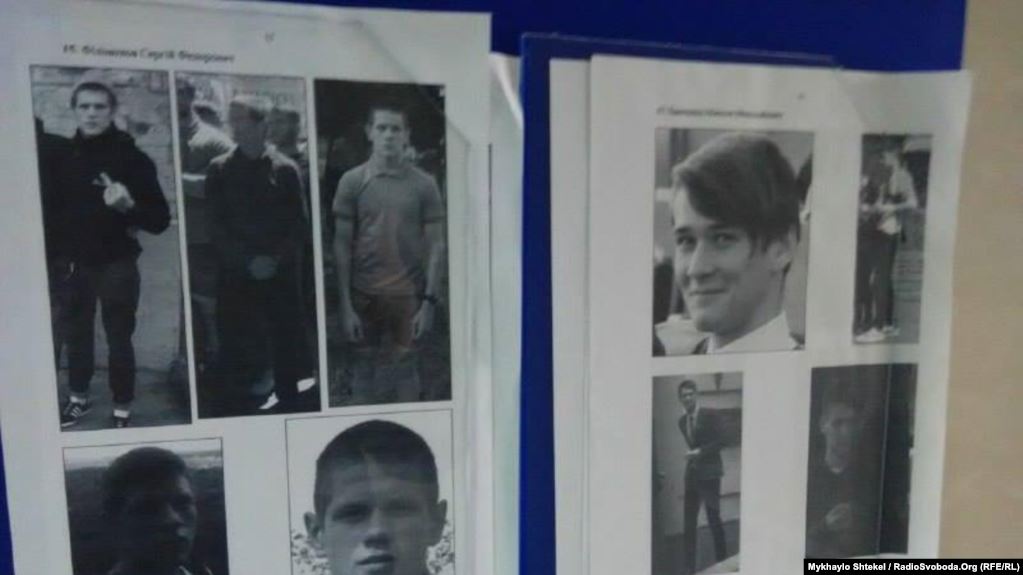

In 2016, Radio Svoboda published an article about an apparent list of C14 members that had been placed up at a police station. Panchenko’s name was 17th on the list of 20 individuals who police thought might be members of C14; a photo with him in it is used as the banner photo for the article. Further, in a 2015 article in Ukrayinska Pravda, Panchenko is quoted as a “representative of the C14 organization.”

A photo from a 2016 article from Radio Svoboda showing Mykola Panchenko, right, as an accused member of C14. (The individual on the left is Serhiy Filimonov, a figure now associated with the Azov movement who has publicly stated he was part of C14 when he was younger).

In a publicly available Facebook post by the accused murderer of journalist Oles Buzyna, known vigilante and neo-Nazi figure Andriy Medvedko, who appears with Panchenko in multiple photos, praised Panchenko for violence.

“[Panchenko] went through a number of hard fights and has rocked a few bastards for the right cause,” said Medvedko.

Panchenko can also be seen, in an undated photo from VKontakte, helping hold a banner with C14’s logo at a rally. The banner is emblazoned with a Celtic cross, a common neo-Nazi symbol.

Mykola Panchenko at left holding a banner emblazoned with a Celtic cross, a well-known neo-Nazi symbol, in an undated photo.

Panchenko is even visible in a photo for a 2017 BBC Ukrainian article on C14; he is in the front row, one of 25 members of the organization.

A photo from a 2017 BBC Ukrainian article, showing Yevhen Karas (front row, fourth from left) and Mykola Panchenko (front row, fourth from right)

The best source for Panchenko’s links to C14, however, are his own words. In a 2017 Facebook post Panchenko outlined how he came to join C14 after the 2014 revolution, and discussed how important it has been in his life.

“Thanks to Sich,” Panchenko wrote, clarifying in a comment below the post that by ‘Sich’ he was referring to C14, “I got not only good friends and brothers, but also a way to find myself.”

“Without it,” Panchenko concluded, “there’d be no Education Assembly.”