The Killing of Muhammad Gulzar

Today, in collaboration with Lighthouse Reports and Forensic Architecture, with reporting from Der Spiegel, and research from Pointer and Sky News, we release an investigation which demonstrates that Greek security forces likely used live rounds on 4 March 2020 against refugees and migrants trying to break through the Turkish-Greek border fence. We identified seven people who were wounded over a period of about 40 minutes, one of whom later died. His name was Muhammed Gulzar.

On 27 February 2020, the Turkish government opened its borders with Greece in an attempt to exert political pressure on the EU over Syria. Thousands of migrants and refugees were funnelled to a single point on the land border between the two countries with the promise of an open route to Europe.

The Greek government responded by deploying its police and military to the region. Migrants were warned not to attempt to cross the border, and the country suspended its asylum system.

On March 4th, after days of tension, violence escalated at the Kastanies-Pazarkule border crossing. Reports emerged of shootings, and casualties. Turkish authorities stated that the Greeks “used live rounds and wounded five asylum-seekers.” The Greek authorities denounced these claims as fake news. There is still no commonly accepted account of what happened on that day.

This investigation was thorough, long and multi-faceted, hundreds of images and videos were watched, analysed, checked and rechecked in order to establish as accurately as possible what happened that day. This article will explain in detail our methodology, and explore the techniques we used during the investigation. All times are in Turkish unless otherwise stated. Note: This investigation contains graphic imagery.

Discovery Of Evidence

One of the most challenging aspects of this case was ensuring that we collected as many videos as possible during the initial stages of this investigation. Anyone who has worked with social media will be familiar with important content disappearing for a variety of reasons. Knowing this, we made sure to discover, log, and download all videos that could be relevant. This included videos taken before, during, and after March 4th.

We searched for keywords using date limited searches across multiple platforms, including Facebook, Twitter, Youtube, TikTok, Instagram, and Whatsapp. Searches were conducted in Arabic, Turkish, Greek, English, Farsi and Urdu. We contacted people who were present that day, including people who were travelling with Gulzar, and requested any further videos they had. We used Hunchley to preserve evidence of these open sources, in case they were later deleted.

The end result was a collection of hundreds of images and videos which were relevant to the investigation. Despite this, we are aware that we did not capture every video filmed that day. In many videos we obtained, other people with phones are visible, recording scenes that would have been useful to our investigation. Unless more people come forward, it is likely that these videos and images will remain on personal mobile phones, or private messaging groups.

The very act of discovery provided the first layer of contextual knowledge necessary to establish what happened that day. Watching these videos enabled us to identify similar scenes being filmed from different angles, or see the same casualties as they were carried across the area. We began to piece the puzzle together.

Identification Of Casualties

Within this content, we began to identify the same casualties that were visible in multiple videos and images. It was possible to track these casualties across the scene not only by recognising their clothing, but also by their unique injuries and the blankets used as improvised stretchers to evacuate them.

Casualties: clockwise from top left: Casualty 1 (source), Casualty 2: Mohammad Hantou (source on request), Casualty 3: Zishar Omar (source), Casualty 4 (source on request), Casualty 5 (source), Casualty 6 (source on request)

Despite us quickly identifying six casualties, Gulzar was the hardest to find and identify. We eventually found a single video where he was clearly identifiable by his clothes. This clip also allowed us to spot that he had actually been caught on three other videos.

Thanks to images, videos, and testimony shared with us by Gulzar’s widow, Sabah Khan, we could see that Gulzar was wearing quite distinctive clothing whilst at the border: black leather boots with zips on the side, blue jeans with one patched knee, a grey striped top, a grey jumper, and a black jacket. In video 43 the black jacket, ripped jeans and black boots are clearly visible.

Left: A picture of Gulzar at the border on 29th February (Credit: Sabah Khan) Right: stills from video 43

Further confirmation that this video depicted Gulzar was provided by images of him after he had been shot, which were posted by the chairman of the Turkish Parliamentary Human Rights Investigation Committee, a member of the AKP. These two images clearly showed Gulzar’s face, his grey jumper, shorts underneath his trousers, and the wound in his side.

Left: video 43, Right: Gulzar after he was shot (source)

These matched images given to us by Sabah Khan of Gulzar’s clothes after they had been removed at the hospital.

Left: Gulzar after he was shot (source), Right: image of Gulzar’s striped top (credit: Sabah Khan)

These videos proved that Gulzar had been at the border that morning, and had indeed been wounded shortly before 1030 AM. Witness testimony collected by Der Spiegel and caught on live streams, images of Gulzar after he had been wounded, and Gulzar’s death certificate all agree that Gulzar was shot.

Geolocating The Videos

Once we had collected videos which we believed showed the events of March 4th, we needed to place them in time and space, a method known as geolocating.

Initially, this was difficult. The area around the Greek-Turkish border is flat farmland, with few reference points apart from the Greek and Turkish border posts.

However, by carefully examining these limited reference points, including more obscure details such as the colour of fields and the direction of furrows, it was possible to build up a comprehensive model of where each video was filmed. This was helped by satellite imagery provided by Planet Labs of this area in March.

For example, this is video 33.

In order to geolocate the scene from this video at 01:22 we built a panorama of stills, allowing us to get a better view of the camera’s surroundings. We can clearly see a thin, green strip of field, surrounded on three sides by brown fields. We can see that on the left side of the green field there are bushes which appear to run along part of its length and, on the right hand side, just in view of the camera, there is a low, circular concrete structure. These features are all consistent with the field seen in satellite imagery taken on March 13, 2020.

This allows us to place the camera at the coordinates 41.649408, 26.496010.

This process was carried out for each of the videos we had collected, placing them in space. In doing so we built up a comprehensive view of a strip of land around the fence from the border gate to one kilometer to the south. These videos were then placed into a 3D model built by Forensic Architecture.

Chronolocating The Videos

The sheer overwhelming amount of videos depicting the chaos of the scene initially presented a challenge.

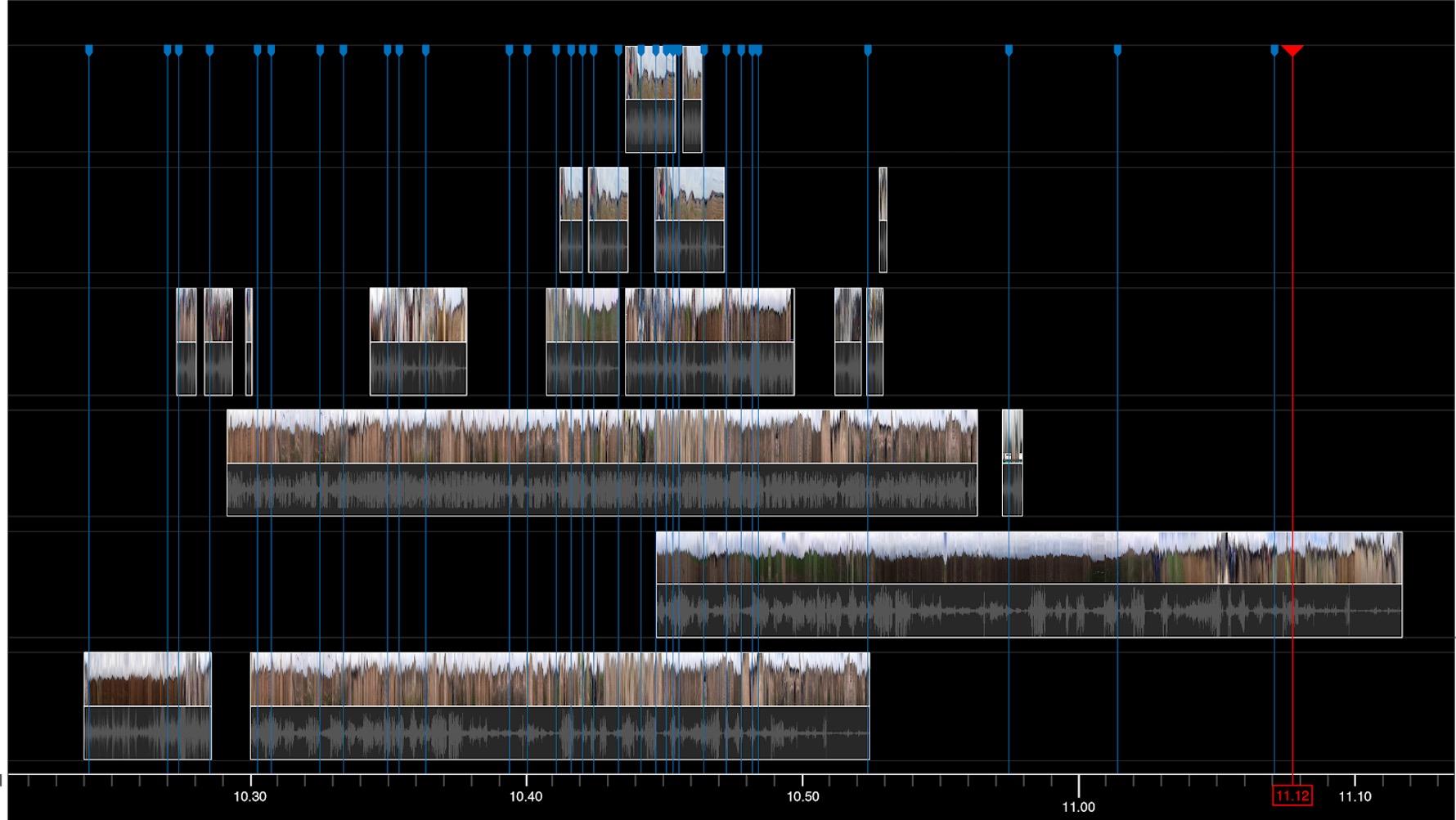

After conducting discovery we identified videos totalling seven hours and 48 minutes which directly related to our time period of interest, namely the morning of the 4th of March. We placed 39 of these in space and time, and closely analysed 24 of them to build an accurate timeline. Scores of other videos were relevant to the investigation, but were filmed outside this time period.

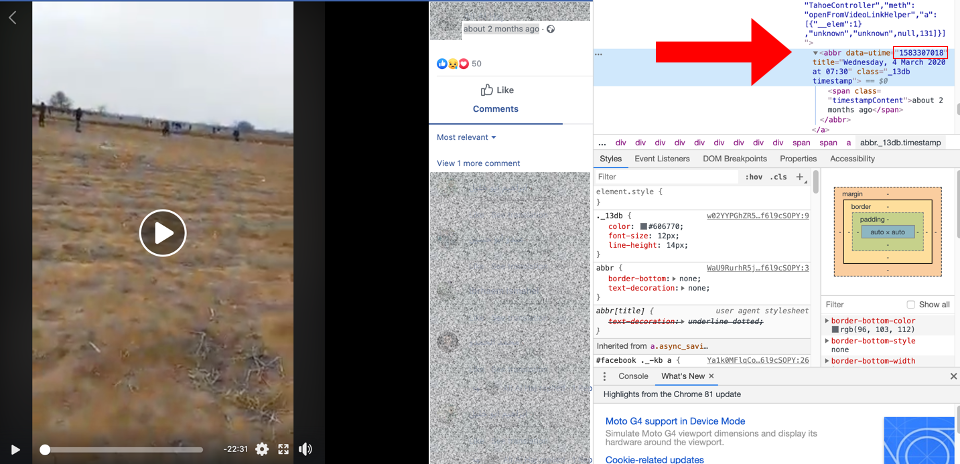

Amongst those videos, we had multiple live streams posted to Facebook. Although Facebook does not tell you the second a livestream started, it is easy to find out. All Facebook videos include a Unix timestamp, which is easily accessible by examining the elements in the webpage. Simply converting this unix timestamp into UTC allows us to establish when a livestream was filmed to the nearest second.

Many of these live streams did not show anything remarkable, however they did capture details which acted as temporal markers, allowing us to place other videos in relation to them.

The most prominent of these markers was the sound of distinct patterns of gunshots. The same distinct patterns could be used as temporal markers across multiple videos, allowing us to place them in relation to each other.

Other details could be used as temporal markers, including announcements over loudspeakers, vehicle horns, and when certain casualties passed a specific geographic point. Using these markers, we were able to place the videos we had collected in time. This method of using a combination of live streams and temporal markers proved to be extremely effective, resulting in a timeline with an accuracy up to a second.

Example of part of the timeline. The horizontal blocks are videos, while the blue lines are the temporal markers

This level of accuracy even allowed us to identify that a photographer’s EXIF data was set incorrectly on his camera. We obtained two photographs taken from the Greek side of the border showing Greek soldiers lined up behind the fence, which the EXIF data indicated had been taken at 11:32 AM Turkish time.

Credit: Socrates Baltagiannis

Several people identifiable in these photographs on the Turkish side of the border were seen in exactly the same positions in other videos we had collected at about 10:40 AM Turkish time. For example, two men were seen in the photographs, one holding a light brown bag. The same two men could be seen in two videos depicting them in exactly the same position.

Top: two men seen in photographs (Credit: Socrates Baltagiannis), Bottom: video 16 and video 32 (source available on request)

We asked the photographer to double check his EXIF data which he then confirmed had been set about 50 minutes later than it should have been.

Tracing The Casualties

Once these videos had been placed in time and space, it became evident that seven people had been wounded over a period of around 40 minutes, from about 10:20 to 10:57 AM Turkish time. These people were first seen wounded in four discrete incidents at different locations:

Casualty 6: before 10:27 AM, location unknown

Muhammad Gulzar: about 10:30 AM, at 41.651439, 26.492400

Casualty 2 (Mohammad Hantou), Casualty 3 (Zishan Omar), Casualty 1 and Casualty 5: 10:39 – 10:42 AM, in vicinity of 41.648675, 26.495926

Casualty 4: 10:57 AM at 41.647304, 26.497158

We created a Google My Map where you can see the routes these people were carried as they were evacuated.

Were Live Rounds Used That Day?

Although the Greek government has dismissed the reports of deaths and injuries caused by fire from Greek forces on its border as “fake news”, we also clearly identified that six people were wounded and one killed that day. Multiple witnesses interviewed by Der Spiegel and heard on videos claim that Greek forces were using live ammunition. We also obtained Gulzar’s death certificate, which stated that his injuries had been caused by a 5.56mm bullet.

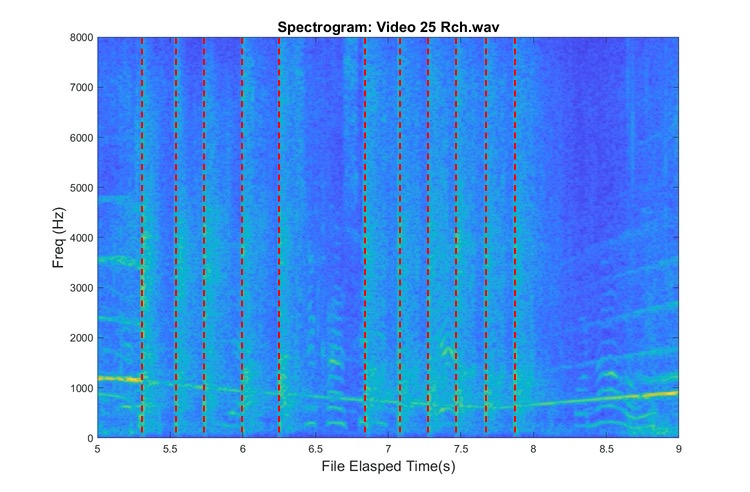

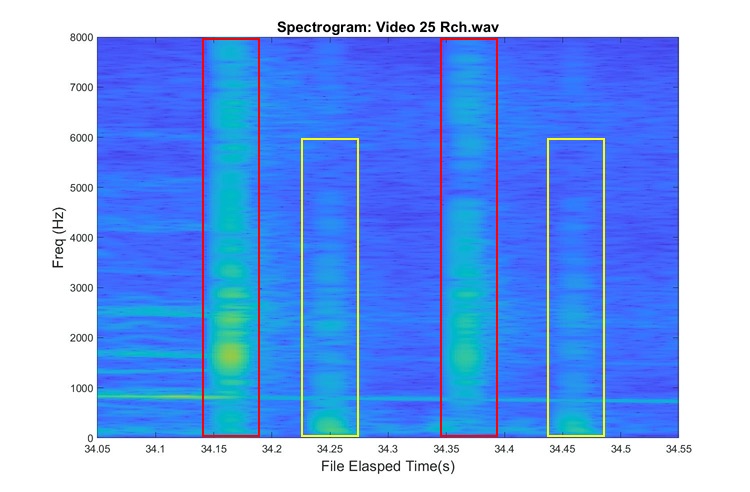

When a supersonic round is fired, it produces two distinct sounds: the sound of the muzzle blast, and the shockwave from the bullet. Since a supersonic bullet, such as a 5.56mm, travels faster than the speed of sound, the first thing heard by a person in the line of fire is a “crack” caused by the shockwave of the bullet, followed by the “bang” of the muzzle blast. Some of the videos we collected appeared to contain the audio signature of live fire.

We sent several of the videos which appeared to contain this signature to Steven Beck, an audio forensic expert. In most of these videos the sound quality was too poor to clearly identify the signature of live fire. However, the analysis concluded that one video contained the distinctive acoustic signature of live rounds: video 25.

Video 25 captures the moment during which casualty 4 was shot at 10:57 AM. This incident was captured on at least four separate videos from different perspectives, two on the Turkish side and two on the Greek side — however, Video 25 was by far the closest to the incident. These videos showed that, at about 10:52 AM, a fire had broken out on the fence line, likely as a result of migrants trying to break through it. As Greek police and soldiers moved to that point to secure it, a fire engine rushed to the scene.

Video 25 begins as that fire engine arrives. Rocks are thrown by migrants from the Turkish side at the fire truck. A fusillade of shots are heard and the cameraman exclaims “gunfire from the Greece Army… I have seen someone who is shot!”. It is this fusillade of shots that was identified as live fire by the audio forensic analysis.

Spectrogram of shots in Video 25. Each dashed red line highlights a shot (Credit: Beck Audio Forensics)

These shots contain the distinctive signature of the “crack” of a supersonic round, followed by the “bang” of the muzzle blast.

Spectrogram of shots in Video 25. The red boxes highlight the “crack” of a supersonic bullet, while the yellow boxes highlight the muzzle “bang” (Credit: Beck Audio Forensics)

Due to the short time between the sound of the muzzle blast and the sound of the bullet passing the microphone, the shooter must have been close to the camera, around 40-60 meters. The energy of the bullet shockwave indicates the rounds were fired from a rifle. The only people we identified within this radius who were armed with rifles or machine-guns capable of firing this kind of round were Greek security forces.

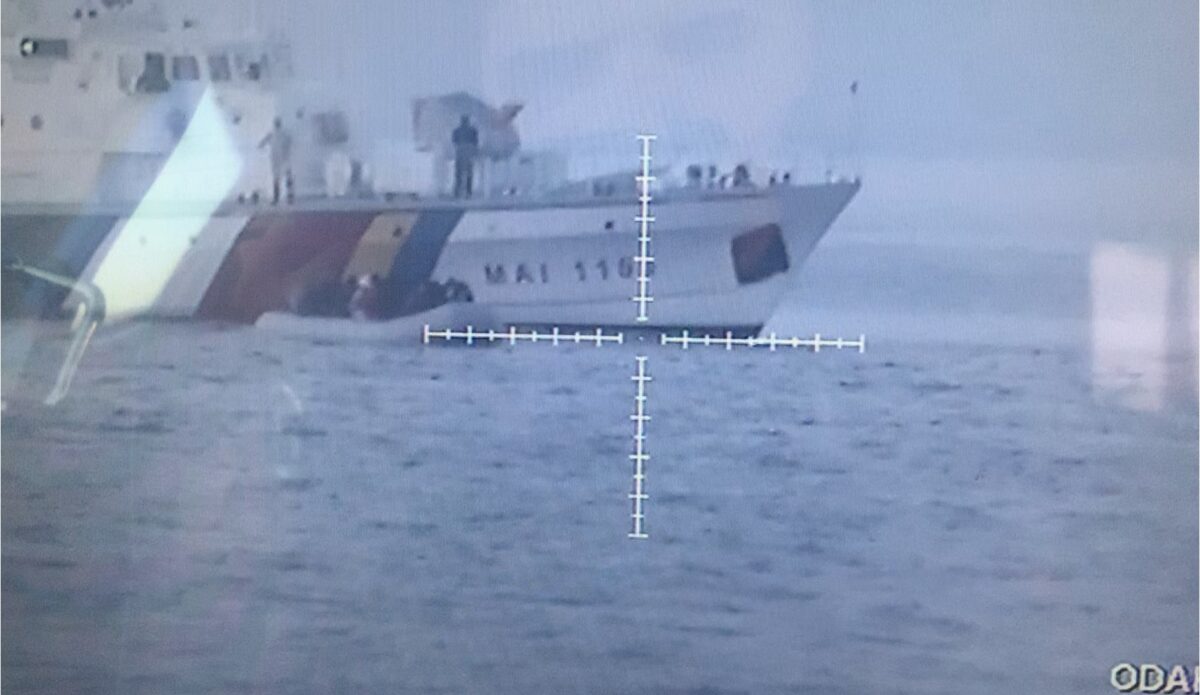

Indeed, throughout the videos that were captured that morning, we could not identify any Turkish security forces along the fence line outside the immediate vicinity of the border post. However, Greek soldiers and police were clearly present along stretches of the border fence that morning. Many of them were armed with M4 and M16 rifles and Minimi light machine guns, all of which fire 5.56mm rounds of the type which allegedly caused Gulzar’s fatal injuries.

Discounted Evidence

Although we used footage from both before and after March 4th for our own contextual understanding, we did not include footage which we could either not verify, or which showed incidents from a different date.

For example, this video appears to show a Greek soldier firing his minimi light machine gun in the direction of migrants behind the border. It was possible to geolocate this video, showing it was indeed taken at the Pazarkule-Kastanies border crossing, however there was no way to be confident about the date or time it was taken.

Similarly, this video of men with drawn pistols apparently taking cover from shooting was used by multiple accounts to make various claims about Turkish actions. Although we were not able to either geolocate or chronolocate it, we were able to exclude it being in the immediate vicinity of the Pazarkule-Kastanies border crossing. The weather also indicates the video was taken at a different time: unlike the morning of March 4th, which was grey and overcast, this video was taken in bright sunlight.

Ethical Considerations

It has always been necessary for open source investigators to take ethical decisions about what information to publish and what information to withhold. Bellingcat has previously chosen to redact the names of some of the Russian crew associated with the Buk that shot down MH17, although we provided their names in full to the JIT.

In the same vein, we chose not to post the full list of 305 names we discovered associated with the GRU.

It was clear from the outset of this investigation that we would have to make careful ethical choices about how we handled certain information. A group of vulnerable people were caught in the middle of a conflict between two states, neither of whom appear to have their best interests at heart. However, we also believed it was in the public interest to demonstrate what had happened as accurately as possible, and open sources were amongst the best material to do that.

As many others have noted, although a person may post content online, the act of sharing that content to a personal Facebook page is a different proposition from publishing it on several platforms with international audiences. Although both are, in theory, publicly accessible, the latter represents an exponentially greater level of exposure.

This difference in anticipated exposure creates a duty of care for the platform that publishes it. At the same time, we recognised that the open source material captured evidence of a grave injustice, and indeed one that may result in legal action.

As such we took certain decisions regarding the material we used for this film. We do not currently plan to make our full list of sources publicly available. When it comes to those sources we have used, we chose to obscure some identities, including both social media handles and faces, that may place that person at risk. This includes the Greek soldiers pictured at the border that day: we wish to be very clear that we do not accuse any specific Greek soldier of firing shots that hit people. We have included pictures of these soldiers in order to demonstrate capability in terms of weapons.

All information will be provided in full for any legal case or inquiry that may result from this investigation.

Conclusion

The extensive open source evidence we collected, combined with witness testimony and expert assessment, clearly indicates that on March 4th multiple people were shot and wounded on the Greek-Turkish border. One of these people, Muhammad Gulzar, later died.

In one incident at 1057 AM, we can establish that a young man, Casualty 4, was wounded; that live rounds from a rifle were fired from a distance of 40-60 meters and that Greek soldiers were within that range. Despite scores of videos from the Turkish side of the border, we could not identify anyone armed with a rifle outside the immediate vicinity of the Turkish border post during the 40 minute period when people were wounded.

Multiple eyewitness reports claimed that Greek forces had fired live rounds along the fence-line that day. This echoes testimony from witnesses who claimed to have seen Gulzar being shot by Greek forces, and his death certificate which claimed he was killed by a 5.56mm bullet.

We call for a full investigation into this incident by the Greek authorities to establish who was responsible for the killing of Muhammad Gulzar.