Flying High: The US Connection to Venezuela’s ‘Narco-Planes’

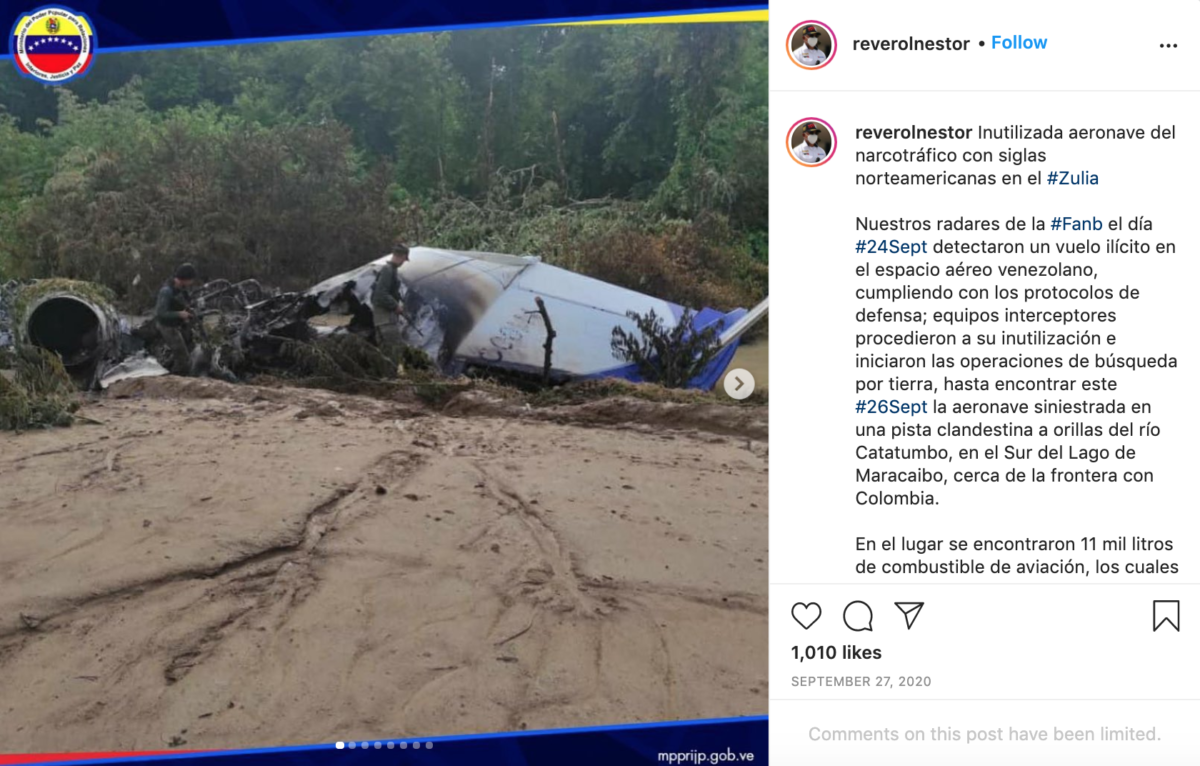

In late September last year, Venezuela’s interior minister, Nestor Reverol, posted several photos to Twitter that showed the wreckage of an aircraft he said had been shot down just south of Lake Maracaibo in the country’s rural far west.

Reverol stated that the “illicit aircraft” was detected by Venezuelan military radar and targeted in accordance with “defense protocols.”

Venezuelan soldiers discovered the wreckage at an unpaved runway cut into the remote landscape two days later. Images showed piles of twisted metal and a few barrels of aviation fuel.

Yet some intriguing clues remained, including a tail fin with a partially visible registration number, parts of the fuselage showing blue and gold livery stripes and distinctive winglets.

The aircraft, Reverol stated, had been registered in the United States, a claim analyzed and confirmed by Bellingcat.

What’s more, it appears to have been just the latest US registered aircraft to be shot down or destroyed in Venezuela in recent years.

Research by Bellingcat – which includes an extensive review of social media posts, corporate filings, aircraft registration databases, ownership documents and local news coverage – shows that the Venezuelan armed forces appear to have destroyed at least 21 aircraft in the country since 2019.

At least 12 of those were registered in the US, although the true number could be higher given the images of some planes analysed were so damaged it was not possible to identify them.

According to the Venezuelan government, eight of these 12 US registered aircraft were involved in the drug trade, with the other four downed or otherwise destroyed for apparently failing to file a flight plan.

A database detailing each aircraft can be found here.

A screengrab of an Instagram post by Nestor Reverol showing a charred “narco-plane” the Venezuelan government claims it shot down over its territory in September, 2020.

Venezuela has long been a transit point for drugs produced in neighbouring Colombia, with aircraft key to transporting narcotics to North and Central America. Some reports even suggest the narcotics trade is so lucrative that aircraft are used by traffickers just once and then destroyed.

While it doesn’t appear from publicly available information that the Venezuelan government always seized narcotics after destroying these aircraft, it did charge at least one individual and arrested three others in relation to drug trafficking. The fact there has been no public complaints from other aircraft owners also strongly suggests they were involved in activities they did not want to publicise.

But why are these apparent narco-planes being registered in the United States? Who owns them? And what, if anything, can this tell us about narco-trafficking operations?

To try to answer these questions, it is first vital to be aware of how aircraft can be anonymously bought, sold and registered in the US.

As it turns out, it can be virtually impossible to know the true identity of a plane’s owner when structures like trusts or limited liability companies (LLCs) are used to register aircraft.

A Matter of Trusts and LLCs

Let’s discuss trusts first.

In the US, those who want to own an aircraft can use a trust – an entity that enables a third party to hold assets on behalf of another person or organization – to register that aircraft with the relevant authorities.

By doing so, the person who in practice uses the aircraft, known as the “beneficiary”, doesn’t have to reveal their true identity on paper or any documentation relating to the aircraft.

The person or organisation holding the asset on their behalf, known as the trustee, is also not obliged to reveal who the beneficiary is in any public records.

How Trusts Work

A trustor places an asset in a trust to be managed by the trustee.

A trustee manages the trust (and the asset) on behalf of a beneficiary. The beneficiary could be the same person or organization as the trustor, but that is not always the case.

The trustee is under no obligation to reveal the identity of the trustor or beneficiary in public records, providing a layer of anonymity to the trust’s parties.

For an aircraft trust, the trustee and beneficiary sign an operating agreement that specifies how the aircraft will be purchased or leased and under what terms the beneficiary will be able to use, control, and fly the aircraft. On paper, the person who owns the aircraft is the trustee. In practice, the person or organization that uses it is the beneficiary.

To be clear, there are many legitimate reasons for individuals or groups to use a trust. These include limiting tax exposure and simplifying export procedures. It’s also important to note that not everyone who uses trusts does so to ensure their anonymity. Some trusts manage the assets of many beneficiaries at the same time.

The Maryland Historical Trust, for example, manages thousands of historical sites throughout the US state. Donors who buy or own landmarks place them in the trust, which can defend, manage, and handle the paperwork for all of the cultural artifacts at once.

Yet a March 2020 report from the US Government Accountability Office (GAO) highlighted a potentially troublesome quirk of trusts. It noted that trusts could be used to provide anonymity and a legal shield for aircraft-owning drug traffickers.

Trusts, the GAO report notes, are not a registration type on the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) form that owners must complete to register an aircraft. Despite that, trusts can still register as aircraft owners because of a loophole in the FAA’s definition of a US citizen.

Although the FAA says only US citizens can register aircraft, as long as a trustee is a US citizen they can in turn register aircraft for anyone else, even for non-US citizens.

More than 11,000 aircraft are owned by trusts in the US, and from our research it appears only a very small number of these are alleged to have been used to facilitate the drug trade.

For those identified for this article, however, we were able to piece together a clear pattern in how they were purchased and registered before ending up a smoking wreckage in Venezuela.

Following the Trail

First, a US-registered aircraft would appear for sale online, usually on a site that specializes in private jet sales like projets.com, aircraft.com, or planephd.com.

At this point, the aircraft we observed tended to have a flight history that showed them operating mostly in North America. Tracking sites would display the aircraft’s prior flights and plane spotting enthusiasts would post pictures of the aircraft arriving at and departing from various airports.

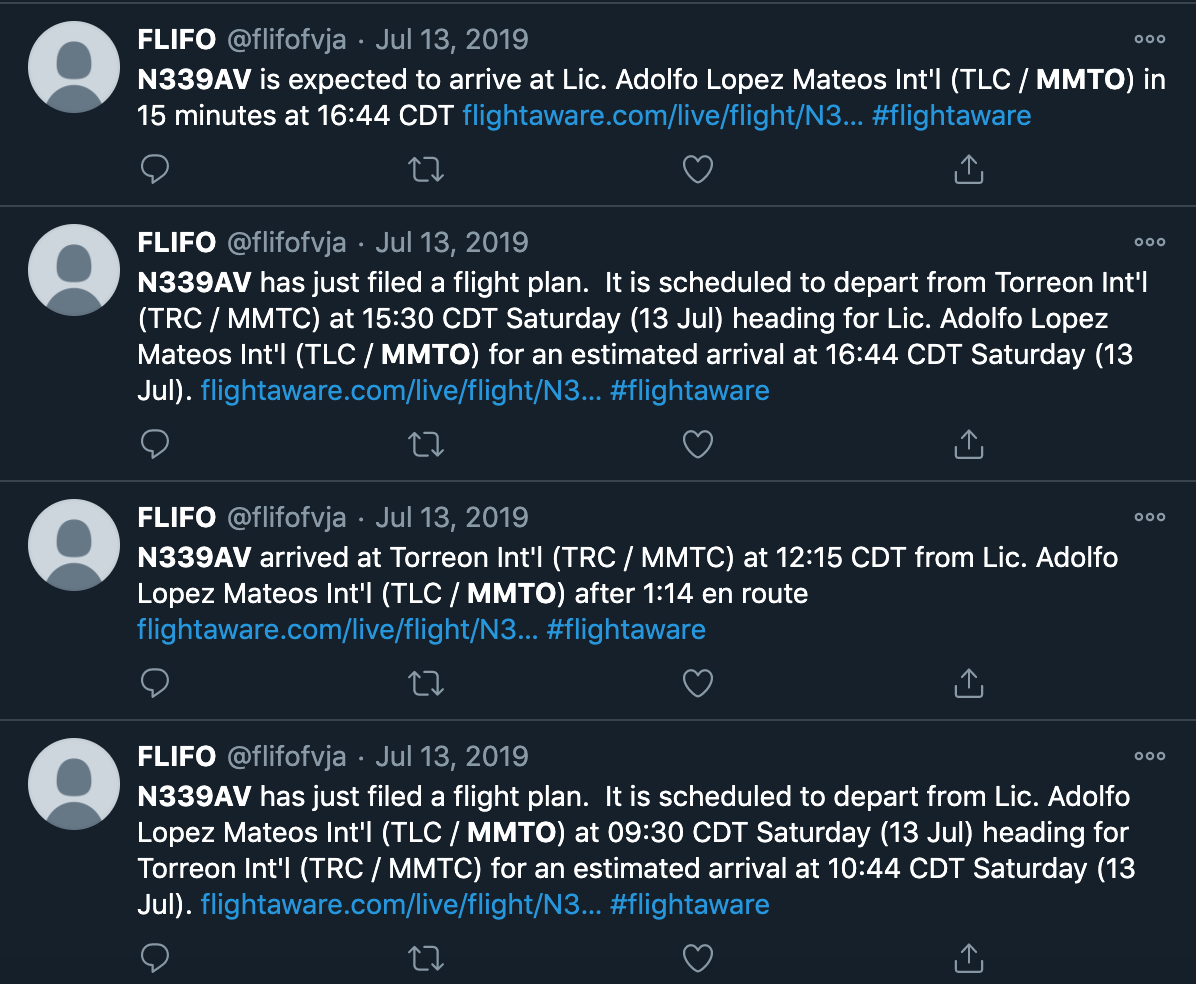

An aircraft that was destroyed in Venezuela in July 2020, N339AV, spent years making consistent flights to and from Mexico’s Toluca International Airport, as a search of the aircraft’s registration on Twitter shows.

After being purchased through one of the aircraft brokerages, the registered owner on the FAA’s website would change to a US-based trust or limited liability company (LLC) — another form of corporate structure in which the company’s officers (those in charge of the LLC) are not held personally liable for the company’s debts or financial losses.

Trusts vs LLCs

A trustor places an asset in a trust to be managed by the trustee. The main difference between a trust and an LLC is that a trust is a legal relationship, while an LLC is, in essence, a business.

The benefits to registering an aircraft with a trust are clear: trusts offer anonymity and a US “citizen” who can register the plane. The benefits for LLCs are slightly less clear, as LLCs have tighter citizenship and disclosure requirements than trusts.

To be sure, there are also ways to establish LLCs to maximize anonymity and tax avoidance when purchasing an aircraft. However, the real advantage for some owners in using an LLC to register an aircraft may lie in the overlap between liability and leases. LLC members cannot be held personally responsible for debts incurred by aircraft in the LLC’s possession. Meanwhile, LLCs can privately rent or lease the aircraft to anyone they want. If the lessee gets into any legal trouble, both the lessee and the LLC members are protected

We primarily focused on trusts because of the pattern of aircraft ownership outlined in the GAO report. However, we also noticed several owners combine the legal advantages of a trust with the business advantages of an LLC by employing an LLC to register the aircraft as a trustee.

The aircraft’s new trust, LLC, or LLC trustee owner would also be reflected on websites that specialize in surfacing aircraft data, like aviationdb.com.

Throughout our research, we weren’t able to identify a single beneficiary owner despite identifying a number of registered owners, trustees, and a few trustors.

The trustors of the aircraft downed in Venezuela are typically law firms, corporate service companies, or tax advisory consultants, while the trustees are LLCs or generic-sounding corporations based in US states with light business regulations, like Utah or Delaware. As mentioned previously, registering an aircraft in a trust or an LLC through an arrangement such as the one described here is not in itself a sign of wrongdoing.

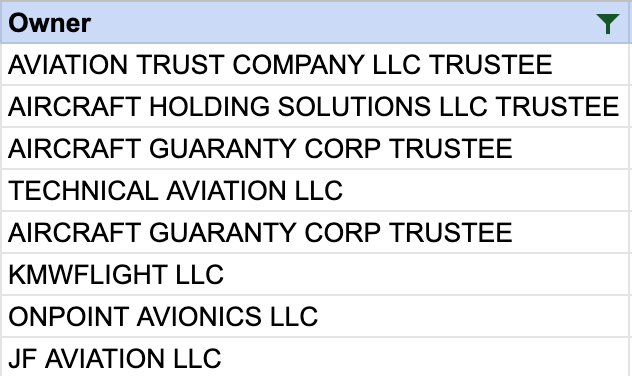

Of the 12 US-registered aircraft that we identified as having been destroyed in Venezuela since 2019, we established that all of those alleged to be narco-planes were registered by trusts, LLCs, or LLC trustees.

The companies shown here are the seven trusts and LLCs that registered aircraft in the US that later ended up destroyed in Venezuela (two aircraft appeared to have been registered by Aircraft Guaranty Corp Trustee).

Again, it is important to note that there is no question of illegality or wrongdoing on the part of the organisations who registered the aircraft that were subsequently destroyed.

Bellingcat reached out to Aviation Trust Company LLC Trustee, Aircraft Holding Solutions LLC Trustee, Technical Aviation LLC and Aircraft Guaranty Corp Trustee to ask about the planes destroyed in Venezuela. We did not receive a response from any before publication. It was not possible to find contact details for KMWFlight LLC, OnPoint Avionics LLC or JF Aviation LLC.

Regardless of the reasons for changing the registration after being purchased via an aircraft brokerage, we noticed new flight patterns for the soon-to-be-destroyed aircraft would emerge .

One aircraft, N515BA, spent most of its life flying near San Antonio, Texas and Murfreesboro, Tennessee. Its registration changed on 1 July 2020, and then flew between Los Mochis and Queretaro, Mexico for the first time on July 19. Later that month, it was found gutted on a rural runway in Zulia, Venezuela. This pattern was repeated across the other aircraft the Venezuelan government said had been destroyed in the country.

Finally, the aircraft would appear destroyed in a series of photos and social media posts released by the Venezuelan military. The officials who published the photos would sometimes announce that a U.S. aircraft had been downed, but other times we conducted open source research to establish that the aircraft was from the US. For example, we cross referenced the paint scheme and partial registration number visible for an aircraft downed in the ocean in August 2020 with sale photos and other publicly available images to confirm that the plane’s US registration number was N400RS.

#ATENCIÒN📢@CODAI_FANB y @AMB_FANB, detectaron una aeronave ilegal, al oeste de la Península de Paraguaná, sin plan de vuelo, fue asistida y persuadida por los medios aéreos de la FANB, realizando maniobras evasivas a baja altura perdiendo el control y precipitándose a tierra. pic.twitter.com/3DHejKs6m3

— CODAI (@CODAI_FANB) August 11, 2020

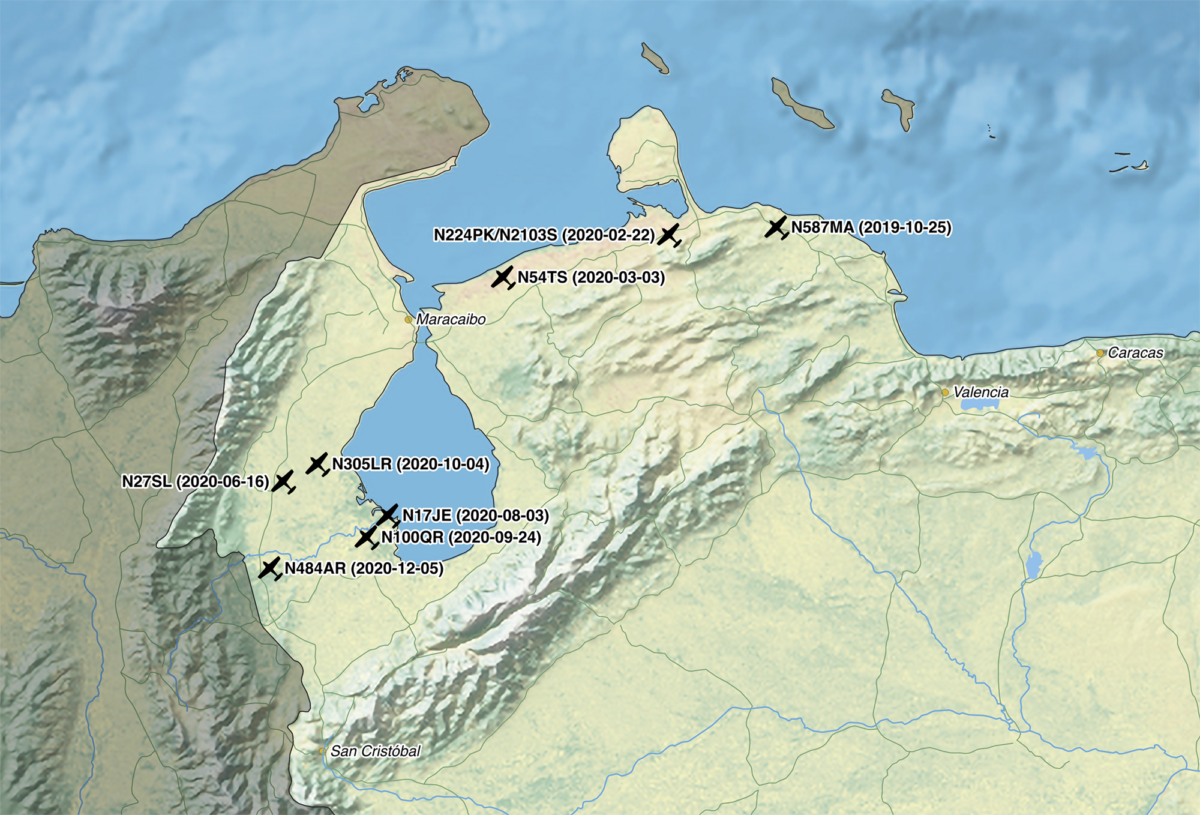

The airplanes were destroyed primarily in the Venezuelan states of Zulia and Tachira, with a noticeable concentration in southern Zulia, near the Colombian border.

Map showing the approximate locations of each US-registered “narco-plane” destroyed by the Venezuelan government, along with the date (YYYY-MM-DD) of the incident as per public statements from Venezuelan officials and/or media reports (Credit: Logan Williams/Bellingcat)

The length of time it took aircraft to follow this pattern of purchase, registration, and appearance in Venezuela varies greatly. The shortest period of time between an aircraft’s final sale and the Venezuelan military’s announcement that they had destroyed it was six days (for N100QR), while the longest was nearly three years (for N54TS).

To examine the path these US-registered aircraft took, let’s examine the history of the aircraft Reverol posted about in September.

(Editor’s note: Beyond this point, some of the linked sites do not go directly to pages that show specific aircraft details. Readers must insert aircraft registration numbers into databases to view the information referred to in full. This is the case for links that direct to aviationdb.com, NTSB.gov and FAA.gov)

N100QR

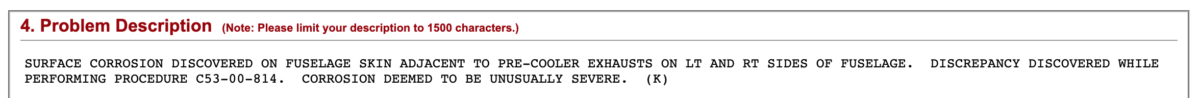

Built in 1982, this Bombardier Challenger 600-1A11 had a long and relatively uneventful history prior to September 2020. It experienced a few issues of wear and tear, such as pitting and vibration upon landing in 2007 and 2008, but it doesn’t appear that those problems significantly affected the aircraft’s performance.

FAA maintenance report showing the aircraft suffered corrosion on its fuselage in 2008. Retrieved from the FAA website.

Before being registered as N100QR in 1996, the aircraft cycled through several other registration numbers. Between 1985 to 2006, it was bought and sold by several industrial and holding companies, as evidenced in the aircraft’s PlaneLogger page.

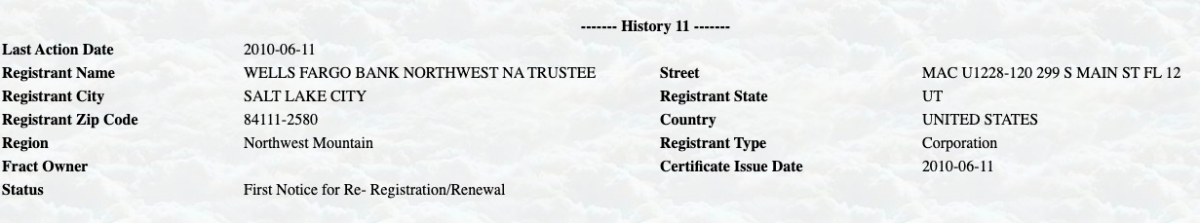

In 2006, it transferred ownership four separate times before ending up with a holding company called Otter Inspirations LLC. It was registered with another holding company, Easy Flight Inc., in 2009 and the aircraft’s first trust, Wells Fargo Bank Northwest NA Trustee, in 2010.

AviationDB page showing Wells Fargo registered N100QR in 2010.

The plane suffered an unusual incident in 2013 while it was owned by the Wells Fargo trust. The aircraft’s landing gear unexpectedly collapsed while landing at Paraguay’s Silvio Pettirossi Airport after flying from Sao Paulo, Brazil. According to local media reports, none of the aircraft’s occupants were hurt and the aircraft was repaired and returned to service.

By scouring social media, we determined that the aircraft was based at the Paraguayan airport at which it experienced that 2013 mishap. In a series of FourSquare, Instagram, and other photos beginning in 2014, the aircraft repeatedly appeared parked at a hangar and flight services company, Hangar Master, attached to Silvio Pettirossi Airport in Asuncion. It underwent routine maintenance at Hangar Master and featured in Instagram flexes – all standard fare for a private jet.

A screen grab taken from FourSquare of N100QR parked at Hangar Master in 2014.

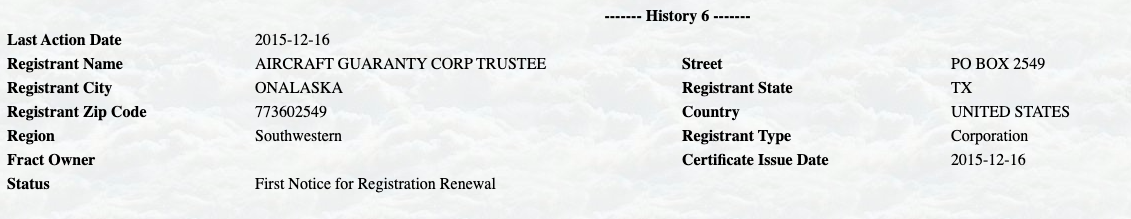

In December 2015, a trust known as Aircraft Guaranty Corp Trustee registered the aircraft. Aircraft Guaranty Corp Trustee has 1,234 aircraft registered with the FAA. However, despite the registration change, N100QR remained at Hangar Master for the next few years.

A screen grab from N100QR’s AviationDB page shows Aircraft Guaranty Corp Trustee registered the aircraft on December 16, 2015.

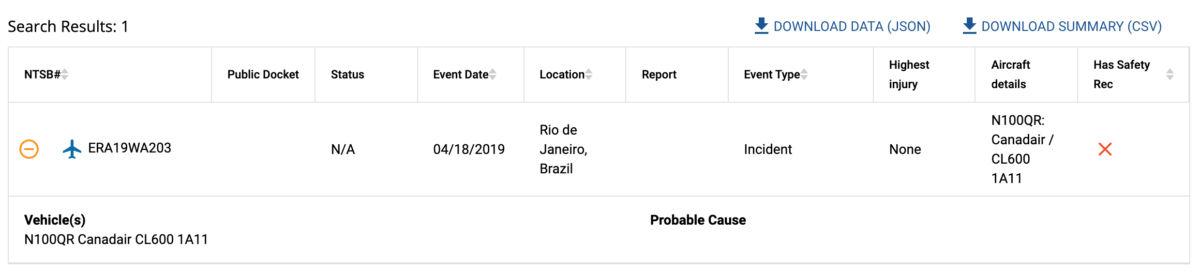

Between 2015 and September 2020, things stayed roughly static for N100QR. It made at least one flight to Argentina but otherwise remained parked at Hangar Master. It did experience an unspecified but apparently trivial problem in Rio de Janeiro in 2019, during which the government of Brazil notified the US National Transportation Safety Board of an incident that affected the aircraft on April 18. No further information appears to be available about that event.

A screen grab of an NTSB report showing minor incident on April 18, 2019 in Brazil.

In September 2020, however, there was an abrupt change in pattern. On September 4, it was reported sold to a buyer in Buenos Aires, Argentina. The address of the buyer as reported to the FAA corresponds to an apartment in the Belgrano area of Buenos Aires, according to a public records website.

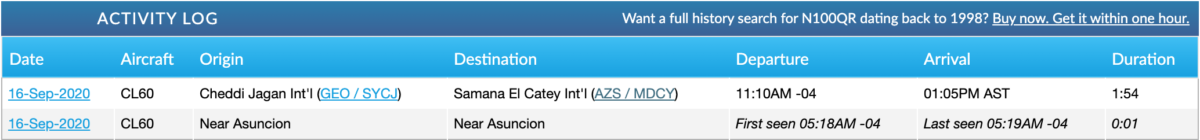

Four days later, on September 8th, an image was uploaded to Facebook showing N100QR on the runway of Silvio Pettirossi Airport in Asuncion, Paraguay. A few days after that, on September 16th, flight tracking sites tracked it on a three-legged flight from Asuncion to Cheddi Jagan Airport in Guyana. Later that day, it flew to Samana El Catey Airport in the Dominican Republic. That was the last time any location data was available for N100QR.

A screen grab from FlightAware, a flight tracking website, shows that N100QR flew from Guyana’s Cheddi Jagan airport to the Semaná El Catey international airport in the Dominican Republic on September 16 2020.

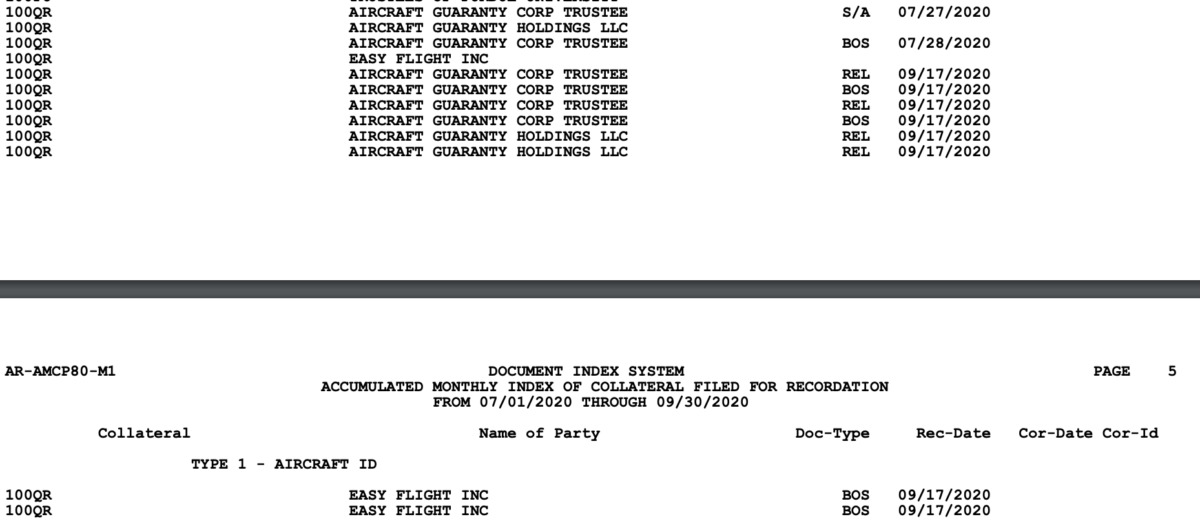

The next day, September 17, a slew of releases and bills of sale for the aircraft were filed with the FAA by three entities: Easy Flight Inc, Aircraft Guaranty Holdings LLC, and Aircraft Guaranty Corp Trustee. Based on the information released by the FAA, it is not possible to untangle the web of ownership, sales, and registration forms created on this day. The FAA only releases the name of the entity that submitted the documentation, the type of document, and the date it was filed.

A screen grab of a document from the Federal Aviation Administration shows a set of bills of sale and releases filed in relation to N100QR on September 17 2020, along with the names of the entities associated with the filings.

However, we do know that multiple successive bills of sale (BOS) and releases (REL) were filed for the aircraft on September 17. Bills of sale and releases are two related types of documents. According to the FAA, a bill of sale is an agreement in which a seller “transfers all right, title, and interest in aircraft” to a purchaser, while a release terminates any existing leases and discharges the aircraft’s former owner from any obligations.

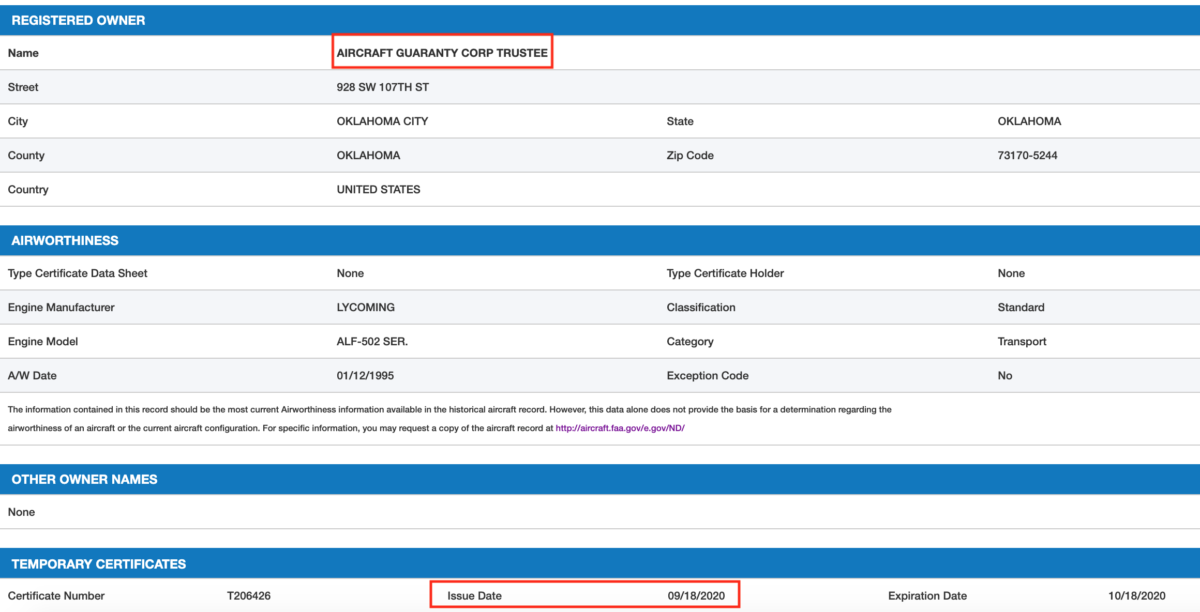

We also know that on the following day, September 18, the FAA accepted and issued a temporary, one-month registration certificate for the aircraft to Aircraft Guaranty Corp Trustee. It is possible that the FAA issued this temporary certificate to allow the aircraft to fly internationally. The administration’s Aircraft Registration Branch will issue planes with a 30-day “Temporary Certificate of Aircraft Registration” to allow an aircraft to be flown outside of the United States if their full registration documents are in order but pending final approval.

According to the Federal Aviation Administration, Aircraft Guaranty Corp Trustee was issued a temporary certificate for N100QR on September 18 2020. This screen grab shows the FAA registration page for N100QR as it appeared in January 2021.

We could not find any open source information about the aircraft’s activities between September 19 and 24, neither on FAA documents nor on social media. Then, on September 27, Nestor Reverol made his Instagram announcement, saying N100QR was detected entering Venezuelan airspace on September 24 and was subsequently “disabled” by the country’s armed forces. Soldiers found what was left of the plane on a runway on the banks of the Catatumbo River, south of Lake Maracaibo, on September 26.

As bizarre as this all was, there is a somewhat baffling postscript to the aircraft’s history. On November 16, well after the aircraft was destroyed, both Aircraft Guaranty Corp Trustee and Easy Flight LLC submitted at least one bill of sale for the aircraft to the FAA.

While this may be a paperwork quirk – perhaps one of the aircraft’s earlier sales was only processed in November – it nonetheless raises additional questions about the trail of ownership and liability surrounding N100QR.

According to the Federal Aviation Administration, Aircraft Guaranty Corp Trustee was issued a temporary certificate for N100QR on September 18 2020. The screenshot above shows the FAA registration page for N100QR as it appeared in January 2021.

Remaining Questions

While the research we’ve done so far has established that there are US-based companies registering planes that the Venezuelan military claims to be destroying, there are a number of questions left unanswered.

First, and perhaps most significant, is who actually are the beneficial owners of these aircraft? We were not able to find a single real owner for any of these planes and only have several fairly remote leads to begin answering this question. As shown by the nine documents filed by the three entities for just N100QR on September 17th alone, the layers of ownership, anonymity, and legal shields surrounding virtually all of these aircraft boggle the mind. If you can figure out who actually owns the aircraft, can you also figure out who buys and finances them?

We’re also curious about the support system that sustains these aircraft through their flights in and out of Venezuela. After their final sale, the “narco-planes” must still have the support structure that any modern jet has: pilots, maintenance technicians, fuel supply lines, vehicles, and so forth. And that’s not even considering the guards, vehicles, and additional support needed for alleged narcotics trafficking. We weren’t able to find much about the people and material that keep these planes in the air.

A third (and related) open question is the geographic distribution of these aircraft. Once the planes “go dark”, where do they actually operate? Cartel territory in Mexico? Colombian coca fields? Are they based in Venezuela’s border areas? If so, it would be interesting to determine to what degree the various governments in each area acknowledge or even know about the narco-planes operating in their territory. Complicating matters is the Venezuelan government’s own credibility issues. Announcements regarding these aircraft tend to come from the social media accounts of Venezuelan officials, and they often contain few details. Without details, it is not possible to independently corroborate many of the claims in these announcements, leaving open the question of whether the authorities are being truthful about these downings.

A final open question centers around the US connection. Do the firms that register these aircraft know how they are being used? If they do know, do they face any legal liability? It seems clear that the true owners of these aircraft are exploiting loopholes in the American aircraft registration system, but it appears that the trustors and trustees themselves operate well within the confines of the law. Further research could determine if the beneficiaries have ever slipped up and exposed themselves to consequences.

Wherever the future research into these aircraft goes, the scheme identified by the GAO is alive and well. America’s lax aircraft registration laws and the Venezuelan military’s quick trigger fingers have built a system that has left the wreckage of US-registered aircraft smoking across the Venezuelan countryside.