Hospitals Bombed and Apartments Destroyed: Mapping Incidents of Civilian Harm in Ukraine

In the central Ukrainian city of Uman, a bloodied body lies lifeless in the street. It’s February 24, and Russia’s invasion of its neighbour has just begun. Debris is strewn across the road and the windows of nearby cars have been shattered. CCTV footage from a nearby shop shows a huge explosion took place here at just after 7am local time. A crater, clearly visible in social media video, appears to confirm a rocket was the cause of the explosion, taking the life of the individual lying motionless nearby.

Two days later in Melitopol, a camera is pointed at the front of a hospital in the centre of the city. The rapid patter of gunfire can be heard as the shaky footage focuses on what is described as the hospital’s oncology department. A number of unidentified munitions strike the building leading to several small explosions. The camera pans around and a giant red cross that adorns the hospital entrance is visible. This menacing and chaotic scene is captured by an individual standing outside residential apartment blocks that look on to the facility.

Bellingcat has been documenting and logging incidents such as these – which have been posted to social media channels – and others that appear to depict incidents of civilian impact or harm since the beginning of the conflict.

Rescuers carry a wounded person on the stretcher as they respond to shelling in central Kharkiv, northeastern Ukraine, on March 1, 2022. (Photo by Vyacheslav Madiyevskyy/Ukrinform/NurPhoto)

Some detail incidents of extreme violence as they take place while others appear to show the aftermath of missile strikes or shootings.

With more videos and images coming to light each day, Bellingcat and members of its Global Authentication Project have begun to log and map these incidents on an interactive TimeMap.

You can explore the interactive TimeMap below or click here to see it in its original (full screen) format.

The Global Authentication Project consists of a community of open source researchers assisting in Bellingcat research through structured tasks and feedback. For this dataset, we are working with many individuals who have Ukrainian language skills and others with local contextual knowledge of the events and places seen on the map. Other participants include individuals skilled in geolocation and chronolocation, with all contributions being vetted by Bellingcat researchers.

The aim of this project is to detail incidents where there is open source evidence of potential civilian harm in Ukraine, as well as attempting to clarify where and when such events took place. Documenting these incidents is important given claims by the Russian government in particular that it is not seeking to attack civilians and avoid impacting civilian infrastructure.

Readers are invited to explore the map by date and location. It must be noted that only events that have been pictured, captured on video or posted to social media are included in Bellingcat’s dataset. It is likely that there will be many other instances of civilian harm that are not documented on video or on social media and therefore not included in the TimeMap.

Even accounting for that caveat, the number of incidents detailed in our dataset and TimeMap at time of initial publication is already significant.

We will continue to update our dataset and the TimeMap as the conflict progresses. The map will also remain online after the conflict ends.

How Does the TimeMap Work?

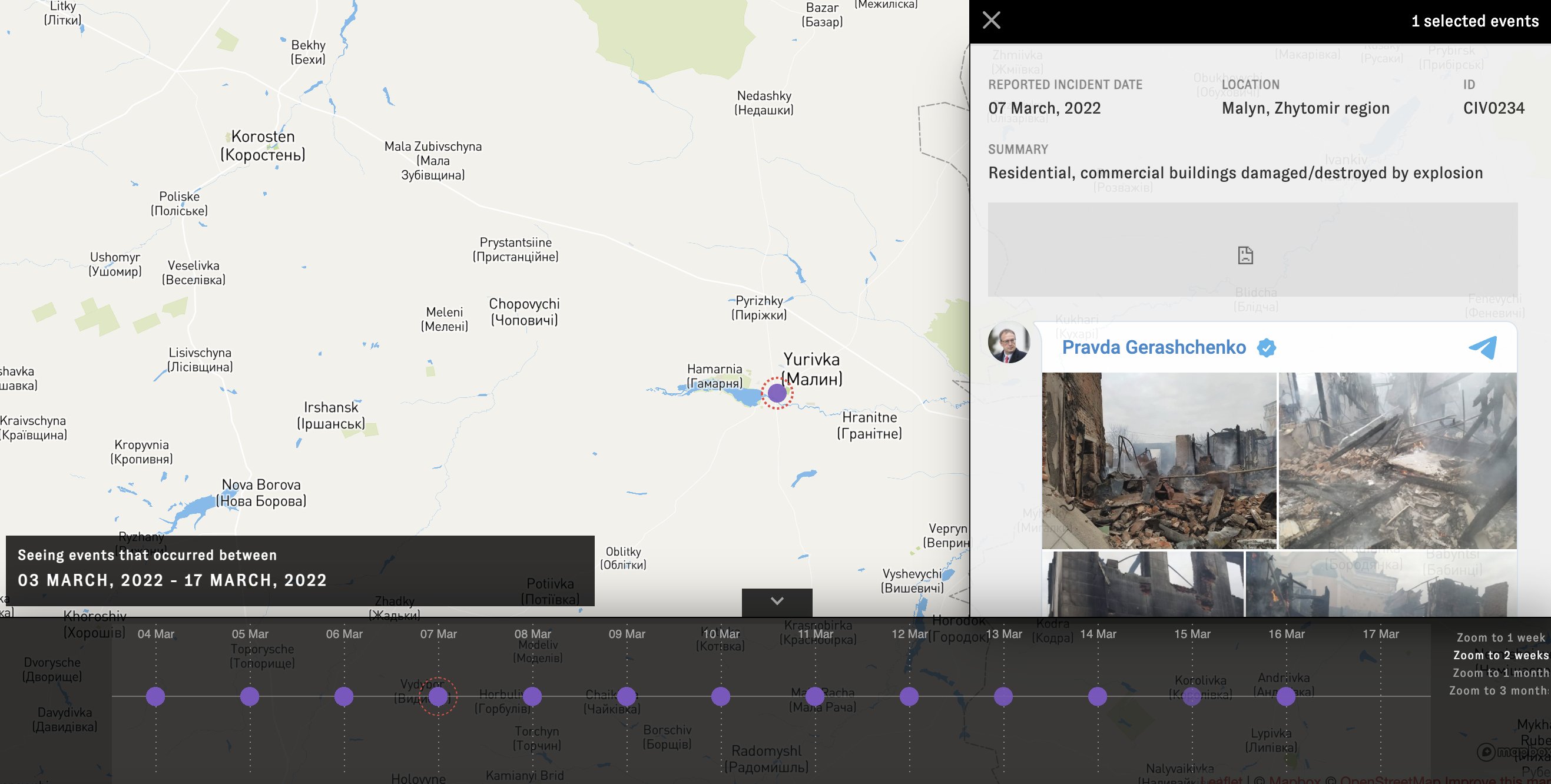

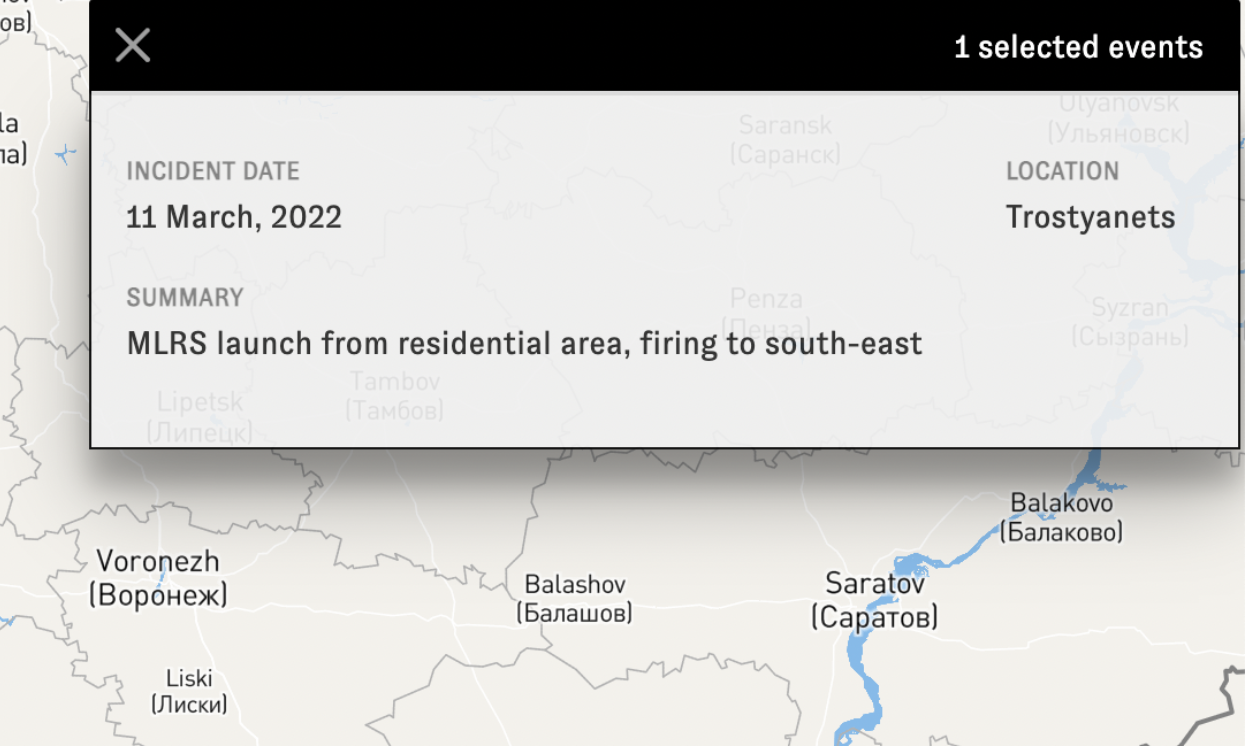

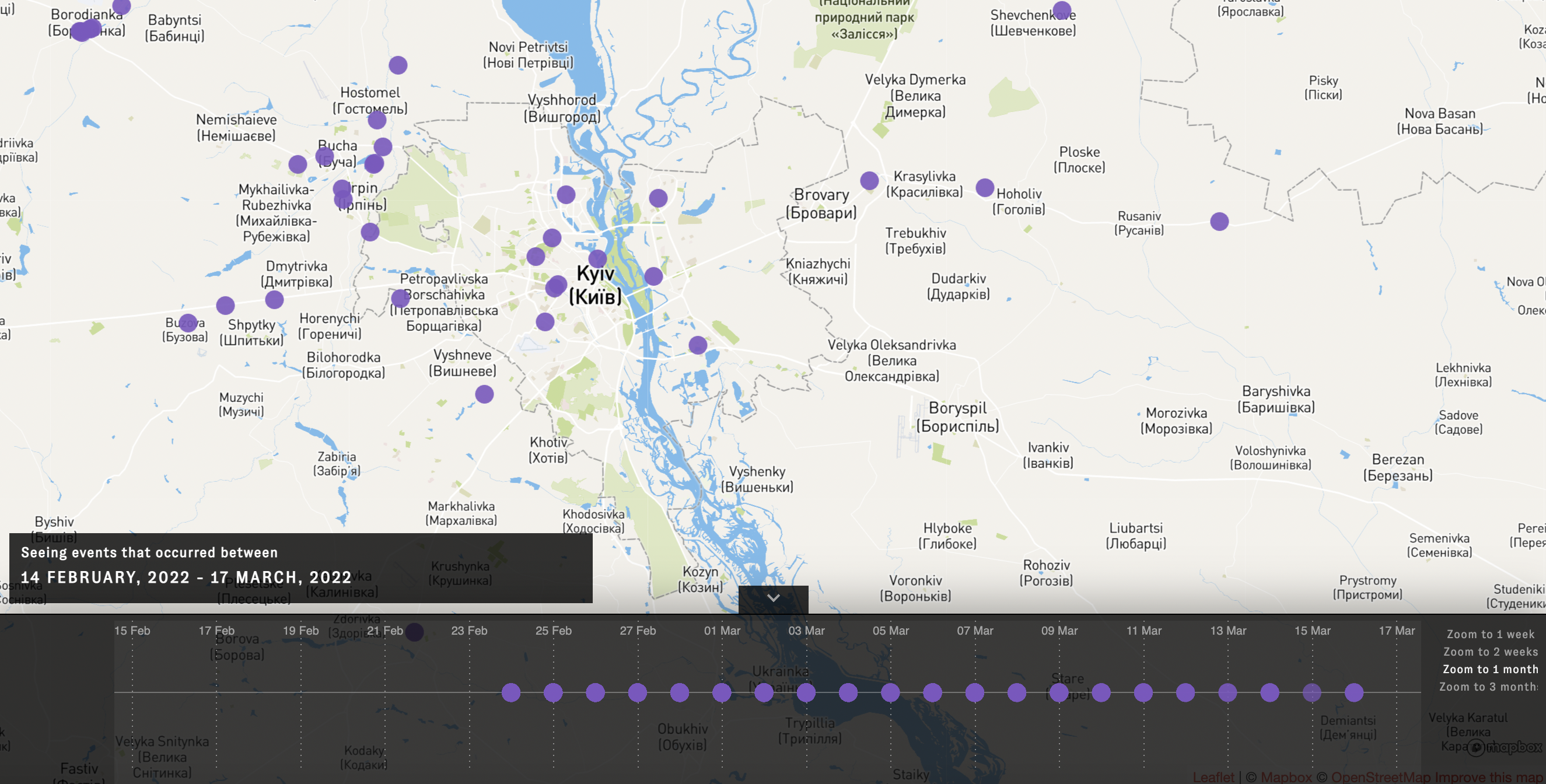

Each dot on the map represents an incident of civilian damage or harm and the location where that incident took place. By clicking on a dot, readers will be presented with information about an incident, often including one or more embedded links to footage or images depicting what happened.

As the footage within selected events has been embedded from social media posts, any views that may be contained within them are not those of Bellingcat or our partners. It is also important to note that any claims within the posts have not necessarily been confirmed or verified by Bellingcat. This is particularly the case in relation to posts that state which party may have been responsible for the incidents detailed. The accompanying description simply details the elements that are objectively observable in the footage.

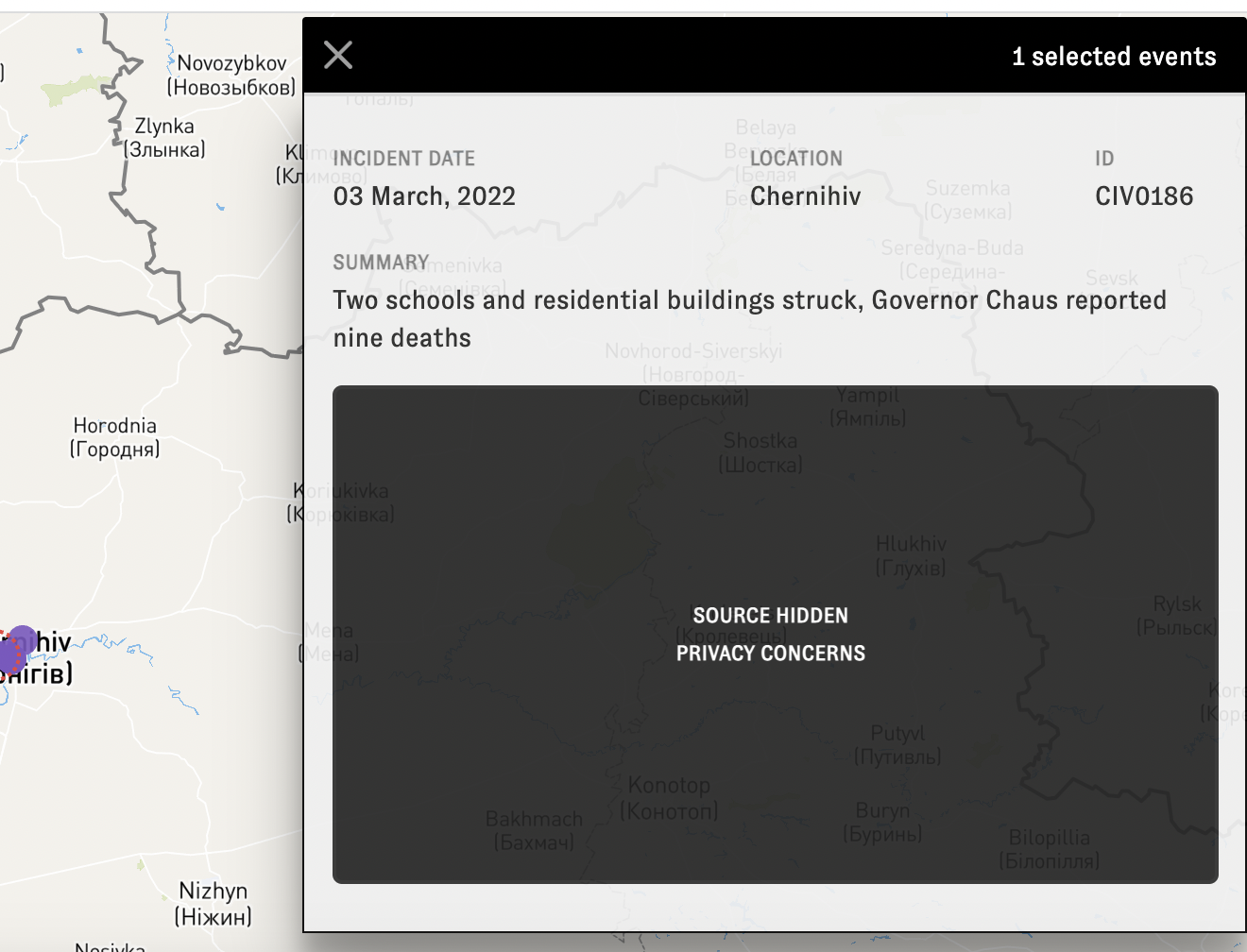

As described in the methodology section that follows, if a user removes the embedded footage from social media it will no longer be visible in the TimeMap format. However, the incident and its description will remain on the TimeMap. A copy of each post will also be archived should they be relevant for any justice and accountability process that may arise in the future (again, these archived posts will not be displayed publicly).

Users can configure the timeline at the bottom of the map to hone in on incidents that took place on particular dates. By clicking on a specific day, a list of the incidents that are logged for that 24-hour-period will appear on the right hand side of the screen.

In some instances, where video or images could potentially reveal the identity or personal location of a content creator, we have taken steps to protect their privacy while still including information about the type of incident that took place.

Users can also view incidents by week, two-week, one-month and three-month periods by clicking on those options to the right of the timeline feature at the bottom of the map.

If users are interested in locating incidents in specific cities, zooming in on the target location is recommended. This provides a far more localised overview than viewing the map from the default perspective that shows the entire country of Ukraine.

A screen grab of the TimeMap focussed in on incidents that have been documented in the city of Kyiv.

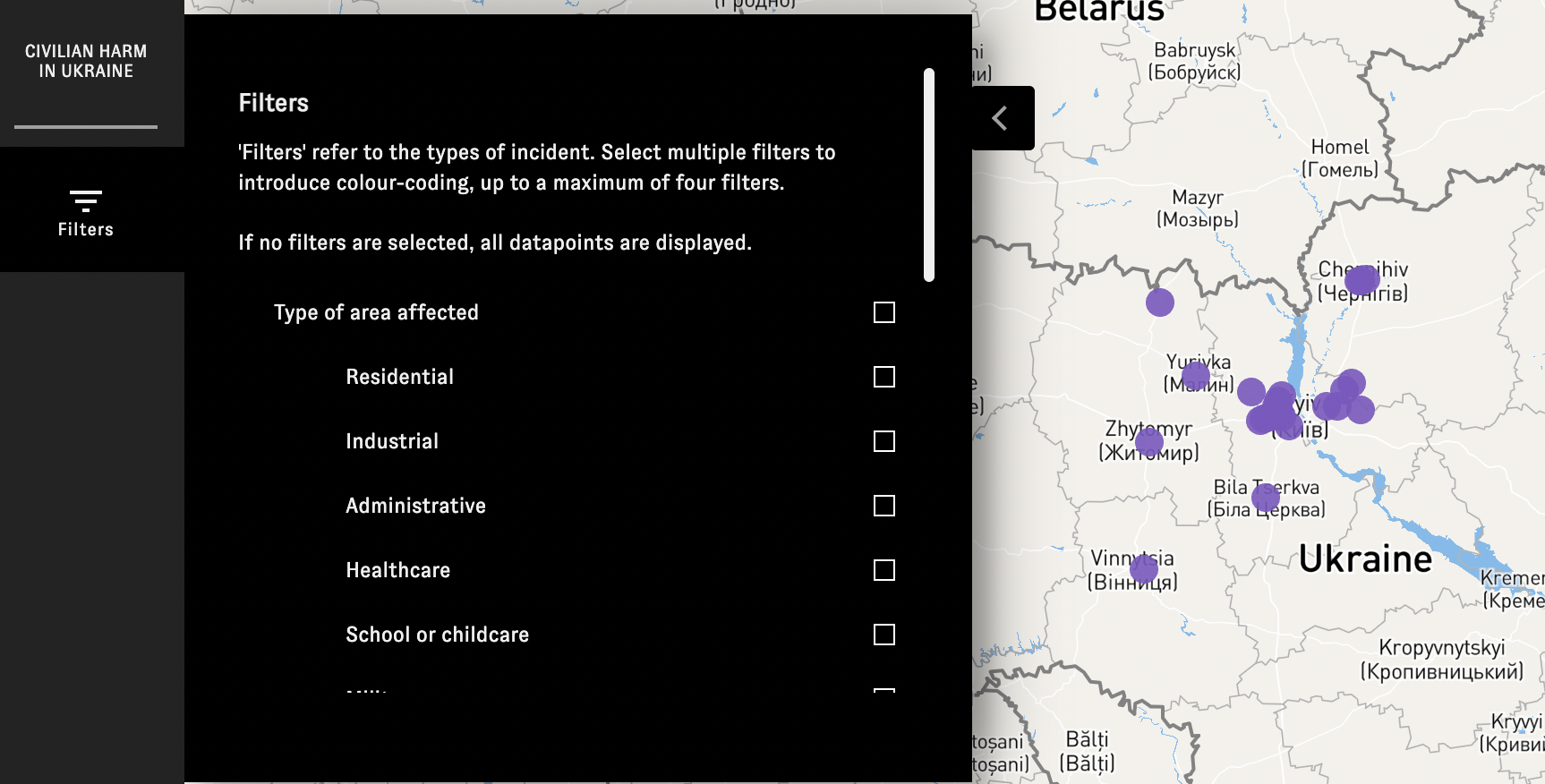

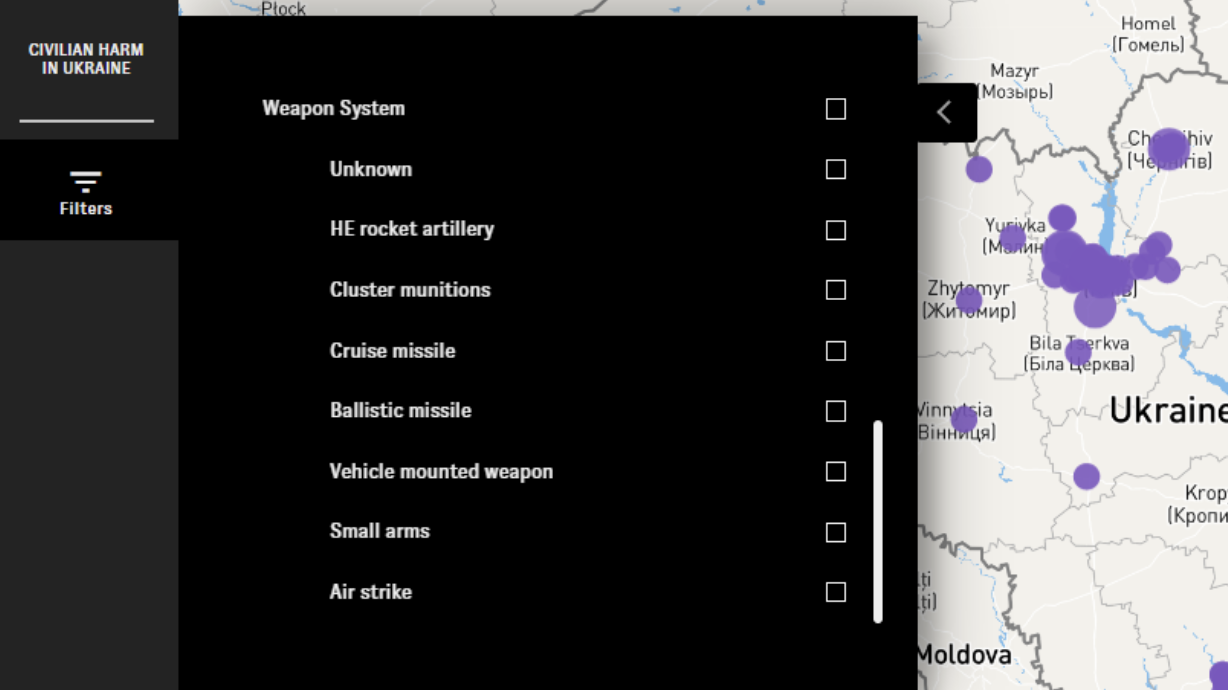

Filters on the left side of the screen also allow users to search the TimeMap by specific types of incident. For example, filters allow for incidents that impacted residential, industrial, healthcare facilities, and more, to be selected. These will then appear on the map with other results filtered out.

If the type of munition or weapon that caused civilian harm or damage can be ascertained with a degree of confidence, this will also be listed in the incident profile. Users can use filters to search for particular types of weapons systems that may have been deployed such as cluster munitions, cruise missiles or even small arms.

The TimeMap Methodology

Scope of Research

This database, organised on Forensic Architecture’s TimeMap platform and customised for this project, is focused on incidents in Ukraine that have resulted in potential civilian harm. These include: incidents where rockets or missiles struck civilian areas, where attacks have resulted in the destruction of civilian infrastructure, where the presence of civilian injuries are visible and/or the presence of immobile civilian bodies. This database began collection on February 24, 2022 and intends to be a living document that will continue to be updated as long as the conflict persists. While we are attempting to collect as many incidents as possible, we cannot possibly guarantee to collect them all nor will we be able to corroborate the locations of all the incidents we collect. Those we do not corroborate the originality or exact location of will not be shown on the map. Therefore, this map is not an exhaustive list of civilian harm in Ukraine but rather a representation of all incidents which we have been able to collect and of which we have been able to determine the exact locations.

Open Source Footage

The links in this map are all open source, meaning they are connected to an open link posted online. These sources were collected by Bellingcat researchers and placed in a database from where they are also being archived locally. After collection, our Global Authentication Project members have determined the location of each of these events (you can read more about the Global Authentication Project and its makeup below). Bellingcat staff then cross-referenced these coordinates to ensure their accuracy. The resolution of these geolocations is within 150 metres of where the incident occurred but the public coordinates viewable on the map have been slightly obscured in order to protect the identity of the creators. Because this footage is open source, the users who uploaded the content are not directly affiliated to Bellingcat or our partners. Any opinions that may be contained within the posts are therefore not those of Bellingcat or our partners. Any claims contained within the posts have also not necessarily been confirmed or verified by Bellingcat, particularly in relation to which party may have been responsible for the incidents detailed.

Verification Level

The data being collected is checked for originality, basic manipulation, and location by Bellingcat investigators. This level of verification is intended to indicate where incidents took place, when and where there are reasonable visual indications of civilian harm. Our investigation plan for the collection of this material and its uses are informed by the Berkeley Protocol on Digital Open Source Investigations. These incidents are also being collected and archived at a forensic level for potential evidentiary use in the future. That level of in-depth analysis and verification will take many months and our goal with this map is to transparently report on the current situation in Ukraine, as it is happening, for public interest. To be clear, these two processes will be separate.

Descriptions

Each incident is accompanied with source links, the exact location determined by our Global Authentication Project and Bellingcat researchers, as well as a brief description of the incident based on what is visually present. The descriptions indicate what is clearly visible but do not attempt to make assumptions about the exact number of casualties or which party to the conflict is responsible due to those factors being difficult to fully determine from short, visual imagery alone.

Filters

On the left hand side of the map, a user can toggle between different kinds of areas impacted. We are characterising the areas as residential, industrial, administrative, healthcare, school/childcare, military, commercial, religious, or undefined. Decisions on these classifications are based on visual evidence in the footage and what the area is reportedly used as. We cannot fully exclude or exhaustively search for the potential of military use in some of these areas.

Source Links/Embedding

We have chosen to embed the social media links directly onto the platform. Should any be deleted by the uploader, they will still be visible on the map, but data on the post, user and footage will no longer be presented publicly. Where sensitive footage posted by individuals might allow them or their location to be identified, we have sought to preemptively take steps to anonymise these users.

Privacy concerns and respect for the dead

This footage is graphic and contains distressing scenes of war and conflict. Many of the areas represented are, at time of writing, also under attack both physically and through online attempts to discredit or harm users posting this content. For these reasons, we have chosen not to share certain posts that might indicate the direct identity of any of the persons filming. We have also filtered out posts that contain images where an immobile body is closely filmed and their identity might be ascertained out of respect for them and their close ones.

A Note on Bellingcat’s Global Authentication Project

The Global Authentication Project consists of a wide community of open source researchers assisting in Bellingcat research through structured tasks and feedback. Our aim is to authenticate events taking place around the world and fill in the gaps of knowledge that exist, particularly in situations where there are vast quantities of data. In creating a community for those interested in open source research, we are fostering Bellingcat’s original aim of solving problems together, to diversify our investigations and promote the use of these skills. For this dataset, we are working with many individuals who have Ukrainian language skills and others with local contextual knowledge of the events and places seen on the map. Other participants include individuals skilled in geolocation and chronolocation, with all contributions being vetted by Bellingcat researchers. As we expand the Global Authentication Project in the coming months, more information will be available on our website and Twitter.

Feedback

This map will continue to change and be updated for the duration of this conflict. We welcome feedback on our methodology, data collection and take transparency seriously. Should you have any direct feedback about the platform, please indicate it on this form.

TimeMap Methodology: Charlotte Godart & Nick Waters

TimeMap Visualisation: Miguel Ramalho & Lachlan Kermode (Forensic Architecture)

Additional Incident Research: Giancarlo Fiorella, Foeke Postma, Narine Khachatryan, Aiganysh Aidarbekova, Annique Mossou, Hannah Bagdasar, Maxim Edwards, Eoghan Macguire, Michael Colborne, Carlos Gonzales, Johanna Wild and members of our Global Authentication Project

Editor’s note: An error in our archiving system between October 21 and November 7, 2022, led to some incidents being published on our TimeMap before they were fully verified. We have fixed this issue and are working to verify all extra incidents.

Bellingcat is a non-profit and the ability to carry out our work is dependent on the kind support of individual donors. If you would like to support our work, you can do so here. You can also subscribe to our Patreon channel here. Subscribe to our Newsletter and follow us on Twitter here.