Is the US Using White Phosphorus in Mosul?

A’maq News Agency, a media outlet linked to the so-called Islamic State, has claimed that the United States used white phosphorous munitions in the ongoing Battle for Mosul on March 11, 2017. This claim was reiterated by two local sources, Salah al-Shorbagy and the Association of Muslim Scholars in Iraq, saying that white phosphorous was used in Mosul. This open source investigation examines this claim in further depth.

Analysis of the video

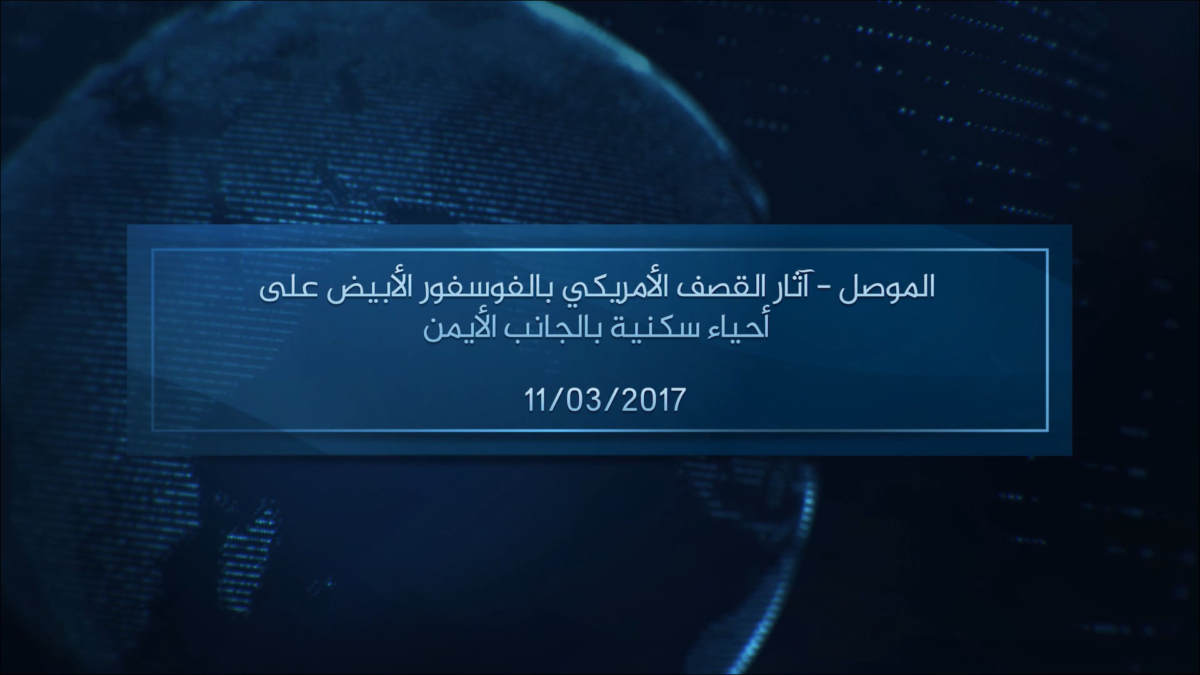

On March 11, 2017, A’maq News Agency published a 74-second long video through its online media channels. The video without its leader was re-uploaded to Twitter, as many A’maq sources tend to quickly disappear off the internet.

The video starts with a title (“Mosul – Aftermath US bombardment with white phosphorous on residential neighbourhoods on the right side”) and a date (March 11, 2017). The “right side” refers in this case to right bank of the Euphrates, which is western Mosul.

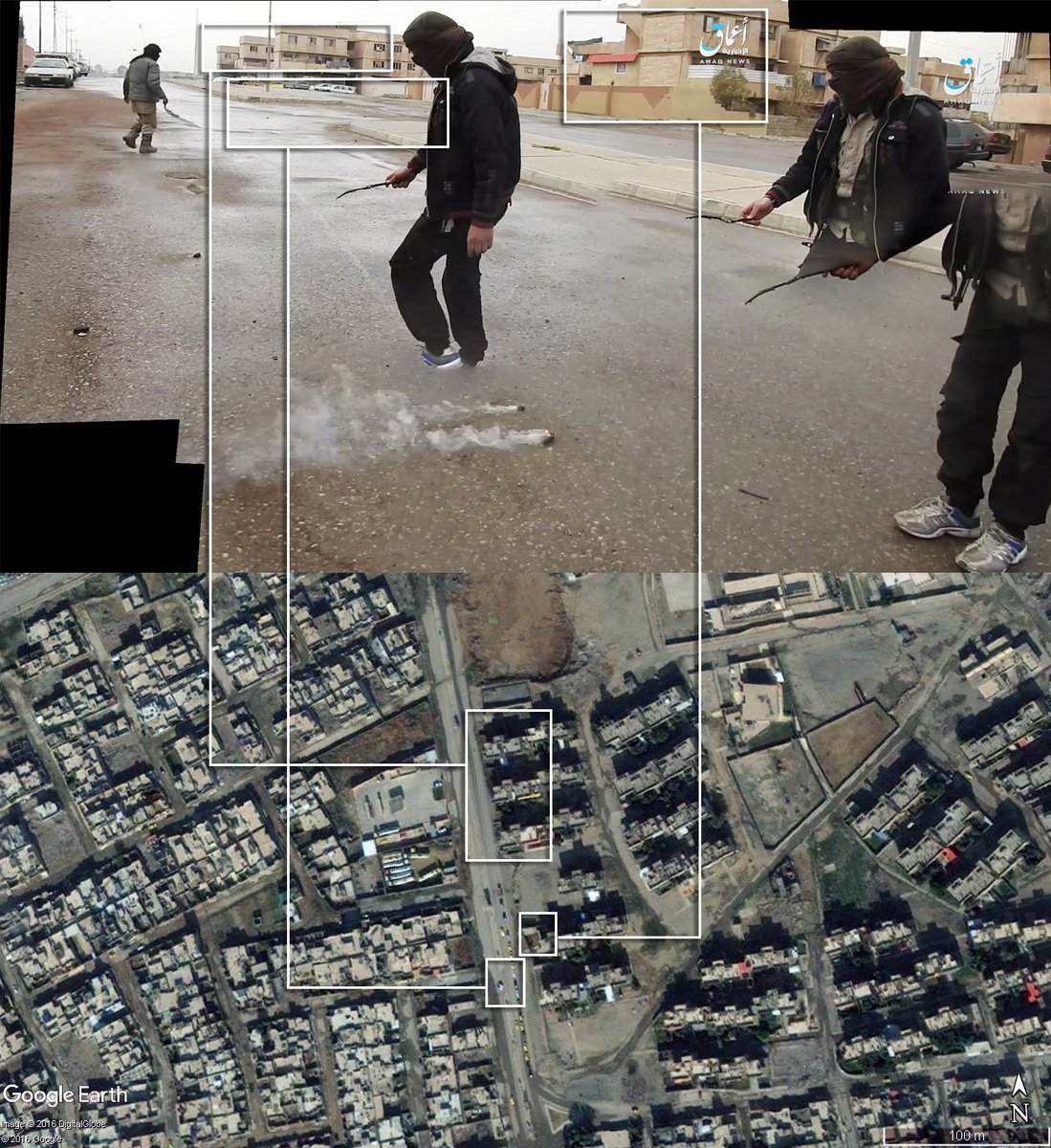

Subsequently, a masked man — seemingly an Islamic State (IS) fighter — is shown standing in a street with a median strip and apartment blocks in the background.

“The enemies of God claimed they did not use chemical substances or white phosphorous in Mosul,” he says, “but the Lord Almighty exposed them and here we see the remnants [of what] they used.”

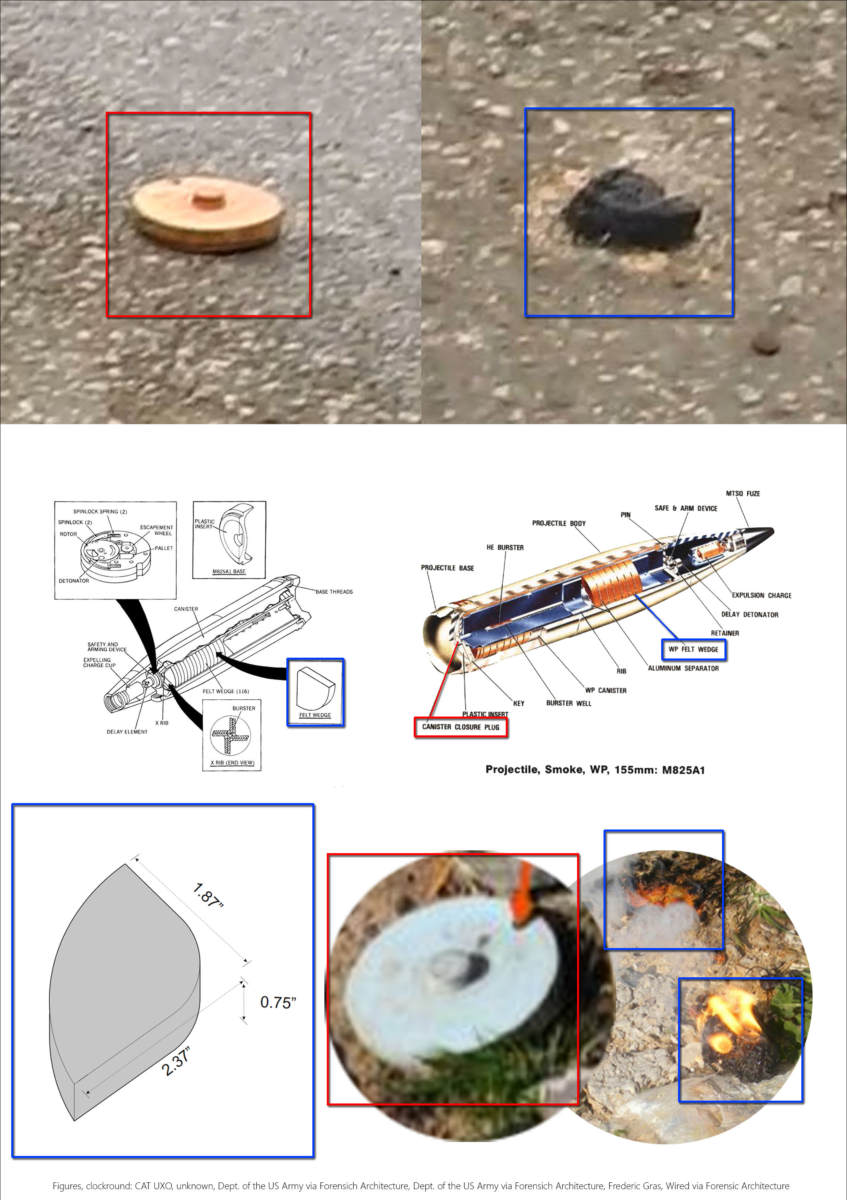

He then walks and points towards several objects laying on the street which catch fire as he pokes them with a stick. The combustion when exposed to oxygen is a characteristic of white phosphorus (WP) smoke felt wedges, which can be used to produce obscuring smoke in a target area.

Furthermore, one of the objects shown in the video strongly resembles a canister closure plug of WP munition. Reference figures of WP, including the 3/4-inch felt wedges, strongly resemble the objects shown in the video.

Geolocation of the video

How to geolocate this video? It is fairly easy, and I’ll explain here how I did it.

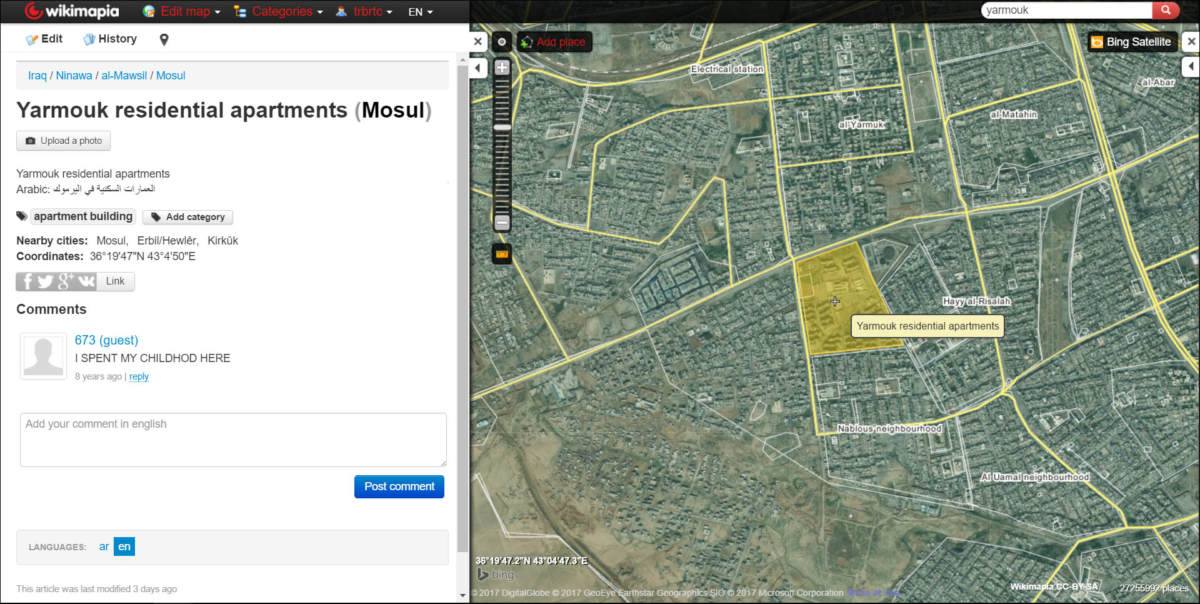

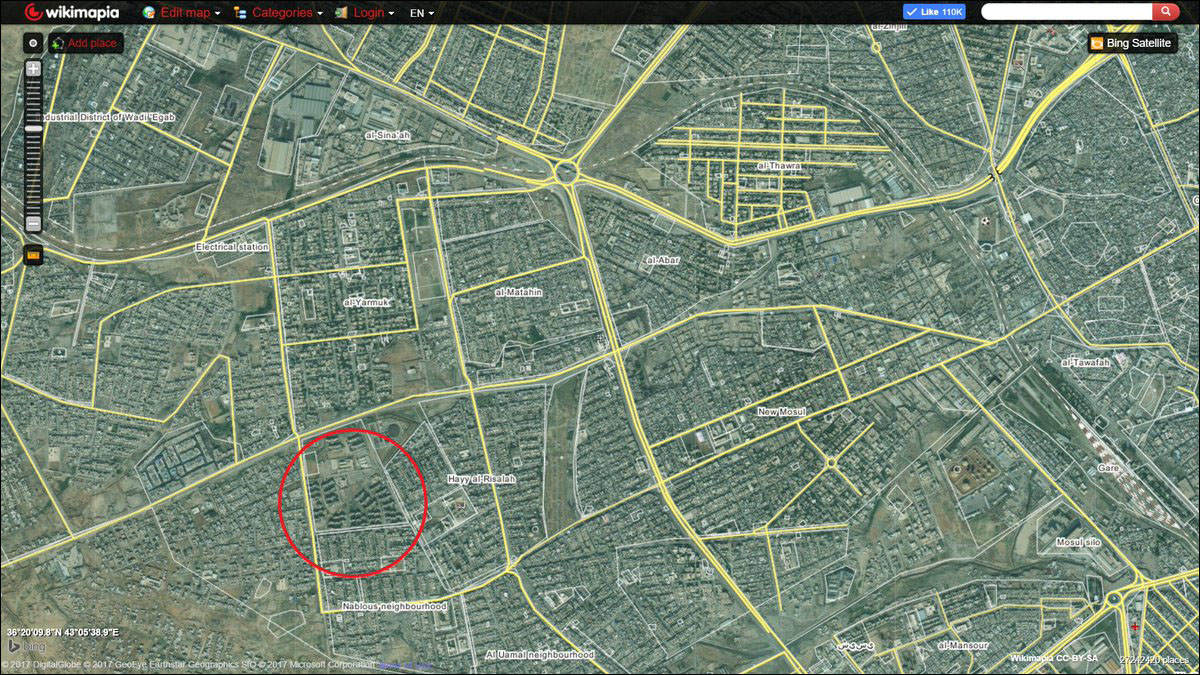

If you speak Arabic, you may noticed that the masked man actually says where he is: “near the Al-Yarmouk apartments”. This location is easy to find on Wikimapia, a privately owned open-content collaborative mapping project which basically allows Internet users to annotate satellite imagery. Once you have found a location tagged as the Al-Yarmouk apartments on Wikimapia, you just try to match elements shown in the video to the satellite imagery and you will notice that it is the exact same location.

But what if you do not speak Arabic? It is still relatively easy. I will explain the process.

If you are trying to geolocate something, you would like decrease the area you are looking in. As the description of the video says it is in Mosul (but not in which part), starting in that city is a good way to start.

Now, what are we seeing in the video that may be recognisable on satellite imagery? Three-storey high apartments blocks (count them!) broadly situated from each other, and a street with a median strip. Now in which parts would IS fighters be able that street and apartments? In the parts of the city it still controls. We can thus exclude territories held by the forces battling IS.

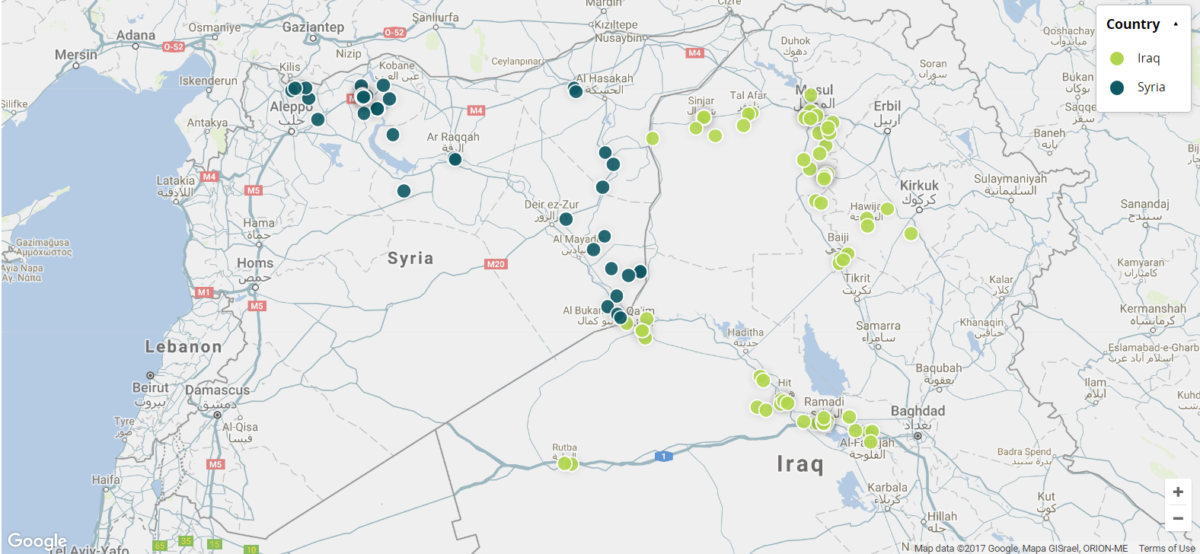

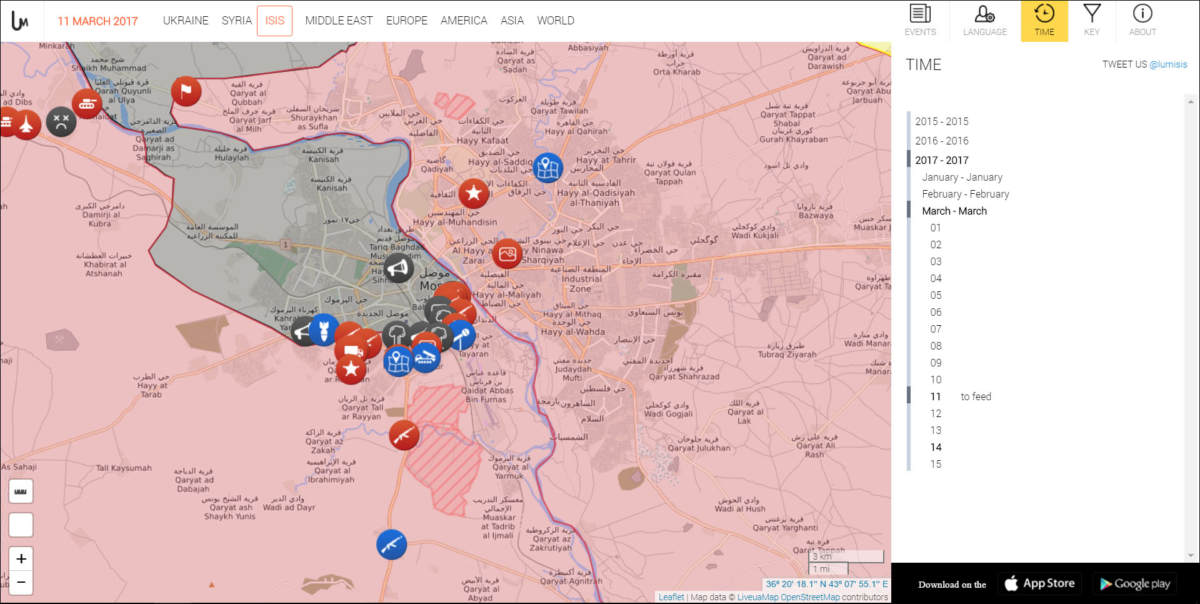

How? Well, there is a great open source mapping project showing territorial control in Syria and Iraq by LiveUAMap focused on IS. Simply go to Mosul for the date we are interested in, and we will see the neighbourhoods that were held by IS at the time.

Then we move on to Wikimapia, which, other than providing annotated satellite imagery, is an excellent way to switch between free satellite and mapping services like Google Maps and Microsoft Bing imagery. And that is important: Google has not updated its imagery for Iraq since 2003 (!). Therefore, I strongly suggest you to use Microsoft Bing Maps, as most of their imagery for Mosul is from November 2013.

Now simply scan the area, which you now is in hands of IS, for relatively high apartment blocks broadly situated from each other. There are not that many.

Can matching elements be found between the satellite imagery of those apartment blocks and the video footage? Yes: the number of apartment blocks, their distance to each other, the median strip – and the opening in between, the street, and the outlay of the streets and the apartment blocks. Even the tree can be spotted on the satellite imagery.

We have thus determined the exact location where the objects resembling parts of WP munition are shown in the video. This is a part of Mosul which formed the frontline between IS and the forces battling the group that day.

A reaction from the US-led Coalition

With the suspected use of white phosphorous and a geolocation, I e-mailed the public affairs office of the Combined Joint Task Force (CJTF) Operation Inherent Resolve, which is under the command of the US’s Central Command (CENTCOM).

In an e-mailed response, CJTF-OIR stated that they are familiar with the A’maq video. However, while explicitly asked, they neither confirmed nor denied they or their allies had used white phosphorous in Mosul that day.

Instead, they stated that, in accordance with the Law of Armed Conflict, “white phosphorus rounds are used for screening, obscuring and marking in a way that fully considers the possible incidental effects on civilians and civilian structures.” Furthermore, “the Coalition takes all reasonable precautions to minimize the risk of incidental injury to non-combatants and damage to civilian structures.”

Previous use of white phosphorous by the US in Iraq

While it is not clear whether the US – or one of its allies – used WP in Mosul that day, it is no secret that the US has used it before in Iraq: most notoriously in Fallujah in 2004 when the US aimed to recapture the city from Al-Qaida militants, and most recently in Autumn last year, as showcased through their own PR photos.

Already in August 2016, a video emerged on YouTube which appeared to show WP munition being fired during an offensive on IS-held terrain. The use could not be verified.

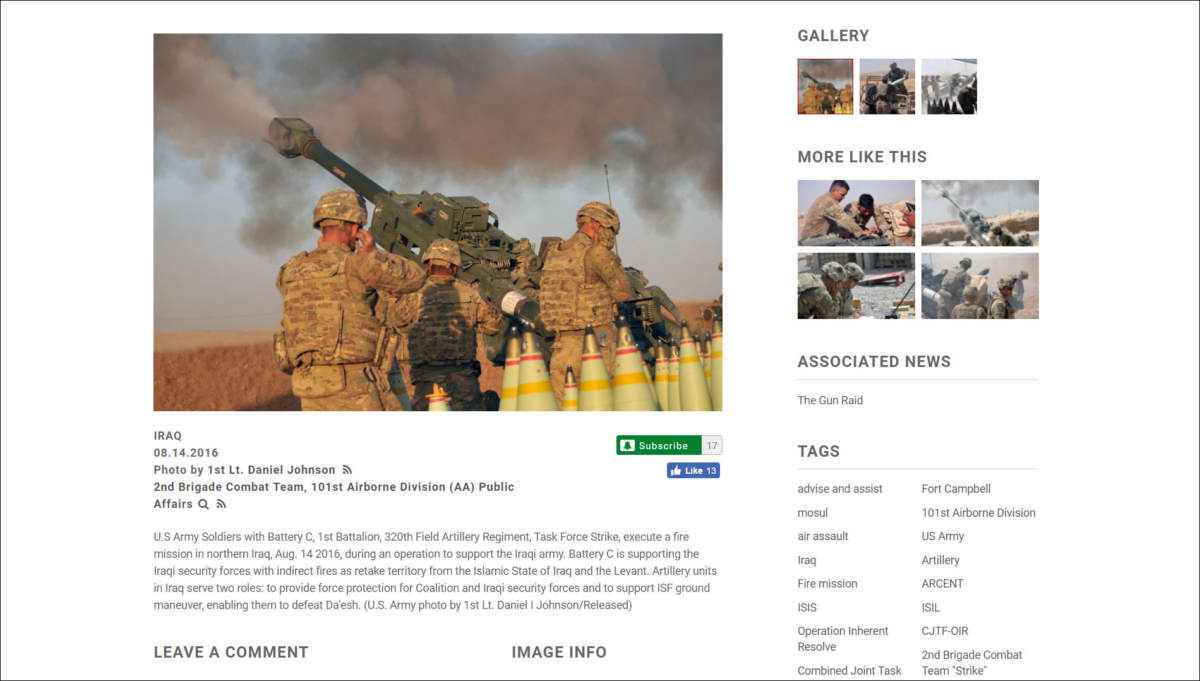

In September 2016, it was clear that the US was using WP munitions in the military operation against IS targets in Iraq based on pictures and videos posted online by the Pentagon, Washington Post journalist Thomas Gibbons-Neff revealed.

Photos posted on DVIDS, a Pentagon-managed public affairs website, show a US Army artillery unit in Iraq using WP munitions, specifically M825A1 155-mm rounds, Gibbons-Neff notes. “The M825A1 shell can create a smokescreen that lasts about 10 minutes and contains 116 felt wedges impregnated with white phosphorus that jettison and automatically ignite when they come in contact with the air.”

Col. Joseph Scrocca told the Washington Post that the WP rounds are used for “screening and signaling”, and that they are used in accordance with the Law of Armed Conflict – similar to what Bellingcat has been told now. The difference is that there appears to be even more care in the statement, saying that “M825A1 rounds are employed […] in areas free of civilian and never against enemy forces”. That statement was later revised to one similar to the statement given to Bellingcat. At the time, WP was used to obscure movements of the allied Kurdish Peshmerga forces securing the Gwer River bridge.

In October 2016, Amnesty International said it had “credible witness and photographic evidence of white phosphorus projectiles exploding in the air over an area north of the village of Karemlesh, about 20 kilometres east of Mosul.” At the time, the organisation warned that WP could pose a deadly risk to fleeing civilians.

Discussion

It is important to note that WP is not an internationally banned weapon, like cluster weapons and landmines. For the use to be illegal, we need to look how it was used. Before doing so, just a a brief note on how WP is used by the military.

WP is used in ammunition like mortar and artillery shells, and grenades. WP ammunition burn and produce smoke when fired, which contains some unburnt and mostly burned phosphorus products (see the ‘Public Health Statement for White Phosphorus‘). The created smoke can mask troop movement, conceal origins of fire, or identify targets to friendly forces.

An example is footage from Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan, in which A-10 pilots are requesting ground controllers to deploy WP to mark enemy positions for gun runs. That moment is captured in the video at the end, at about 5:12. In the video, the pilot refers to “Willie Pete,” a common slang term for white phosphorus.

However, incendiary weapons can inflict terrifying injuries that can cause severe, thermal and chemical burns when in contact with human skin. Therefore, the use of WP deserves scrutiny. Amnesty International has classified the use of WP in or near civilian areas as an indiscriminate attack that may account to a war crime, and Human Rights Watch has fiercely criticised Israel for firing WP shells over densely populated areas in Gaza.

Furthermore, WP was intentionally used by the US in Fallujah’s urban areas in 2004 as a “psychological weapon against insurgents in trench lines and spider holes,” according to an article written by a captain, a first lieutenant, and a sergeant, in the US Army’s Field Artillery Magazine of March/April 2005. “We fired ‘shake and bake’ missions at the insurgents using WP to flush them out and high explosive shells (HE) to take them out.” The siege of Fallujah, resulting severe destruction and subsequent humanitarian concerns, were partly utilised by insurgents groups to bolster more support for their operations.

These kind of applications raises serious concerns over potential misuse, if the laws of armed conflict is not followed strictly. The use of WP in or nearby populated areas poses both an acute and long-term risk of civilian and first responders exposure to these toxic remnants of war, and long-term risk for reconstruction work, as clean-up of WP requires expertise and special equipment.

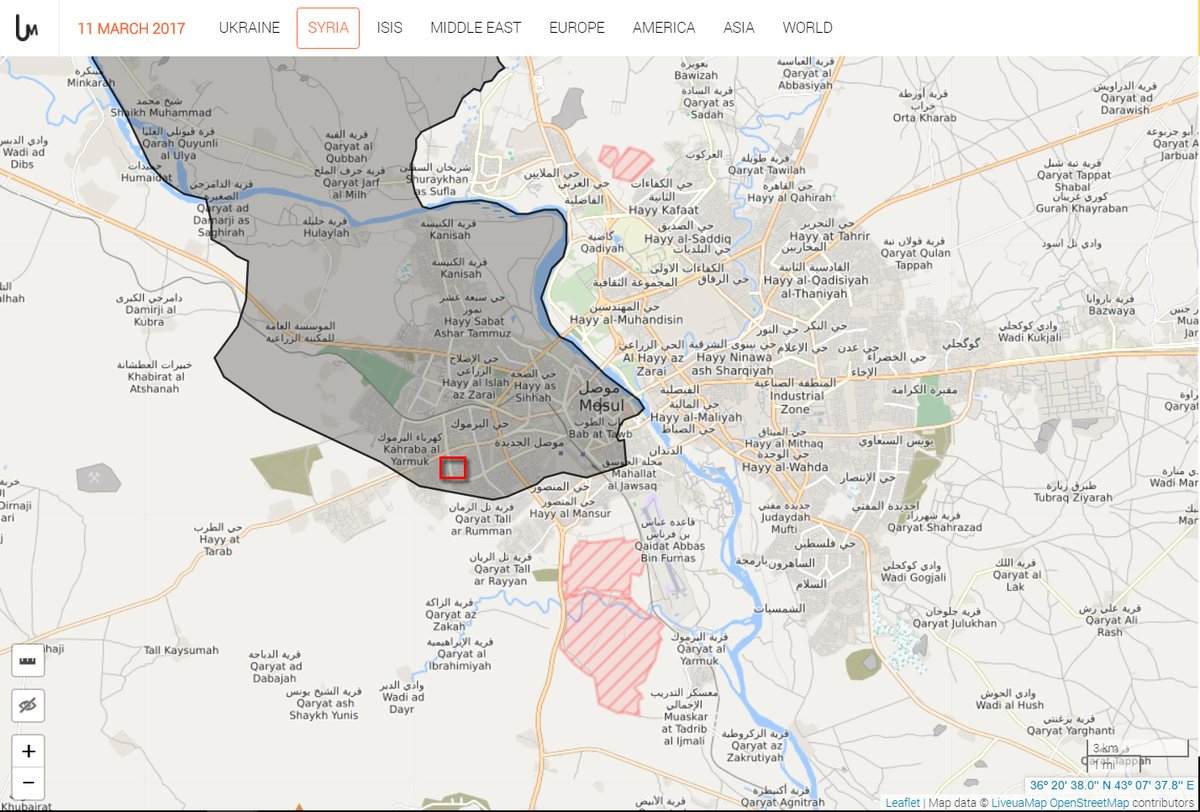

As shown on the map below, the location where the seemingly WP felt wedges were found (yellow pin) is relatively close to a small open space (circle 1), namely a junction. This may have been the targeted area to obscure friendly troop movement in just half a kilometre south (circle 2), where according to the reports of that day the frontline was in Mosul.

It has not been possible to establish whether civilians were present in the Al-Yarmouk neighbourhood and it surroundings, though as it is a densely populated area, this may well have been the case.

For that very reason, Mark Hiznay, the associate arms director for Human Rights Watch, told the Washington Post that he was wary of the US-led Coalition use of WP munitions – especially if these would be used in the Battle for Mosul.

“When white phosphorus is used in attacks in areas containing concentrations of civilians and civilian objects, it will indiscriminately start fires over a wide area,” Hiznay told the Washington Post. “U.S. and Iraqi forces should refrain from using white phosphorus in urban areas like Mosul because whatever tactical military advantage is gained at the time of use, it will be far outweighed by the stigma created by horrific burns to civilian victims.”

No multimedia or textual information could be found hinting towards civilian injuries or casualties due to the alleged use of WP.

Conclusion

The international US-led Coalition appears to have used white phosphorous (WP) munitions in their battle against the so-called Islamic State (IS) in Mosul, Iraq, based on a video posted online by an IS-linked propaganda outlet. It is known that the US has used WP in Iraq, and while aware of the video, the Coalition neither confirmed or denied the specific use of WP in Mosul. It has not been possible to establish whether civilians were present at the targeted site, but when WP is used in residential neighbourhood the tactical military advantage may well be outweighed the stigma of using WP in civilian areas, as a Human Rights Watch employee stated earlier. While the statement was made in the context of attacks, it also holds for other usages of WP. No multimedia or textual information could be found hinting towards civilian injuries or casualties due to the alleged use of WP.

The author would like to thank Aric Toler and Wim Zwijnenburg for feedback on the article, as well as the following persons for helping with identifying the objects in the video: Thomas Gibbons-Neff, Richard Stevens, Marc Garlasco, Frederic Gras, Veli-Pekka Kivimäki, Mike Weber Sr., Donatella Rovera, Peter Bouckaert, and Wim Zwijnenburg. Also thanks to Twitter-user @MENA_Conflict for bringing the video to my attention, @Putintin1 for listening closely to the spoken Arabic, and @AfarinMamosta for a link to the August 2016 video.