Geolocating Libya's Social Media Executioner

Warning: this article contains graphic material. Update: Incident One, Four and Five have been geolocated.

In Short:

- The International Criminal Court issued its first ever arrest warrant solely based on social media evidence;

- This warrant is a significant development and aligns the Court with the realities of today’s conflict zones;

- All seven videos on which Libyan commander Werfalli is charged with murder as a war crime can be found online;

- With the help of the verification platform Check, Bellingcat is crowdsourcing the geolocation of the locations shown in these videos. Three out of seven videos have been geolocated so far.

- Open source information is a potential goldmine of evidence, though there are potential challenges with using this information in a legal setting, which will be discussed in relation to the Werfalli case.

Introduction

On August 15, 2017, the International Criminal Court (ICC) issued its first ever arrest warrant solely based on evidence collected on social media.

The arrest warrant accuses Mahmoud Mustafa Busayf Al-Werfalli, an alleged commander of the Al-Saiqa Brigade in Libya, of mass executions in or near Benghazi.

The use of social media evidence is a significant development, as it aligns the ICC with the realities of many of today’s conflict zones. It also allows anyone with an Internet connection to access the evidence themselves, as it is all open source information – the kind of information we always base our investigations on at Bellingcat. For that reason, this article examines the social media evidence used in the case in further depth.

Firstly, a contextual background will be given to Werfalli and where the alleged incidents took place related to so-called “Operation Dignity” in and around the Libyan city of Benghazi.

Secondly, the seven incidents based on seven separate videos will be examined in further detail. We have tried to extract as much information as possible out of the videos, and asking our readers to help geolocate the execution site. (Update: So far, already two videos have been geolocated.)

Thirdly, the social media evidence of this specific arrest warrant will be discussed in the light of the promise and peril of open source evidence. There is no doubt that open source information is a huge potential source for legal evidence, but what are the methodological challenges in assessing and eventually using these materials?

Contextual Background: Operation Dignity

Since a bloody uprising started against the government of then-President Muammar Qaddafi in 2011, Libya has been in a state of unabated violence and conflict. After the relatively quick fall of Qaddafi, the country has been divided into rival political and armed groups. Opposing government and parliaments roughly divide Libya in an eastern and western side.

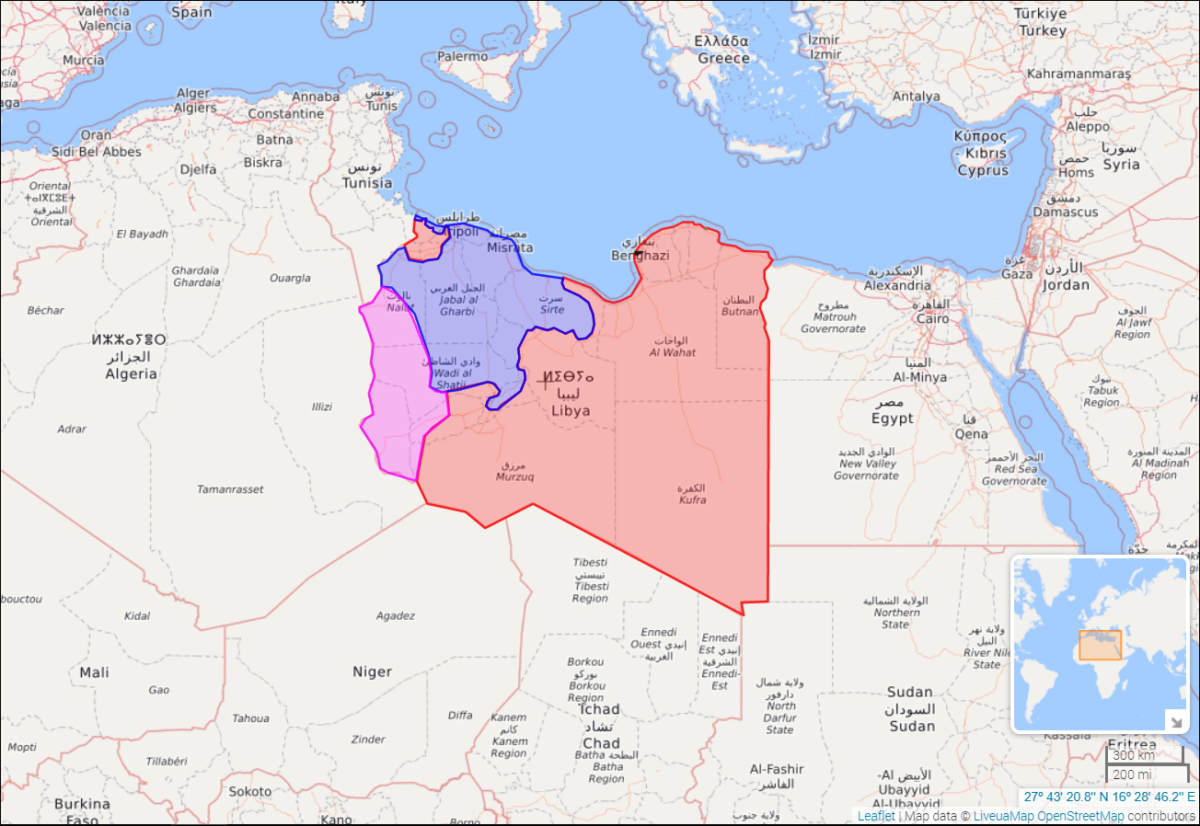

Libya is roughly divided into an eastern and western section, as this LiveUAmap of approximate territorial control as of August 31, 2017, shows. The LNA-controlled areas are in red, the Libyan Dawn-controlled areas in blue, and the pink area represents the territory held by Tuareg militias. The black strip at Benghazi are jihadist groups. This is an oversimplified map of territorial control, as it does not show Amazigh (Tuareg) or Toubou controlled areas.

The Government of National Accord (GNA) is seated in the western part of Libya. As a rival of the eastern-based House of Representatives, the GNA has the armed support of several groups, most notably the Libya Dawn group – a coalition of pro-Islamist militias which attacked Tripoli International Airport in the summer of 2014 and has controlled many of Libya’s coastal cities since. The GNA are the internationally recognised authorities of Libya, and has received outspoken support from a number of Western countries, including the United States (US), the United Kingdom, and France.

The eastern part of Libya, and a small area west of Tripoli, are controlled by a coalition of armed groups named the Libyan National Army (LNA). This force of former army units, ex-revolutionary groups and tribal coalitions is under the command of General Khalifa Haftar, a dual citizen of Libya and the US. The eastern-based parliament is known as the House of Representatives.

Parts of Benghazi, Libya’s second-most populous city on the eastern Mediterranean coast, have been under control of a coalition of Islamist groups since the 2011 revolution. This coalition of Islamist groups became known as the Benghazi Revolutionary Shura Council (BRSC), which includes groups like Ansar Al-Sharia, the February 17 Revolutionary Martyrs’ Brigade, the Rafallah Al-Sahati militia, and the eastern Libya Shield Brigade.

In May 2014, General Haftar launched “Operation Dignity” against the BRSC in and around Benghazi. The operation continued until at least March 18, 2017. One of the groups taking part in the anti-BRSC offensive were the Libyan Special Forces, colloquially known as the Al-Saiqa Brigade.

The Saiqa Brigade was originally part of Qaddafi’s army, but defected in an early stage of the 2011 uprising. Being active especially in western Benghazi in recent years, the group reportedly consists of around 5,000 soldiers. Werfalli, the subject of the ICC arrest warrant, is said to be a Saiqa Brigade commander since at least 2015.

During the periodic fighting in and around Benghazi, Werfalli is said to have been directly responsible for the execution of 33 persons who were either civilians or persons hors de combat. “There is no information in the evidence to show that they have been afforded a trial by a legitimate court, whether military or otherwise”, the arrest warrant states. There was thus an alleged denial of fair trial for the killed individuals – making them unlawful.

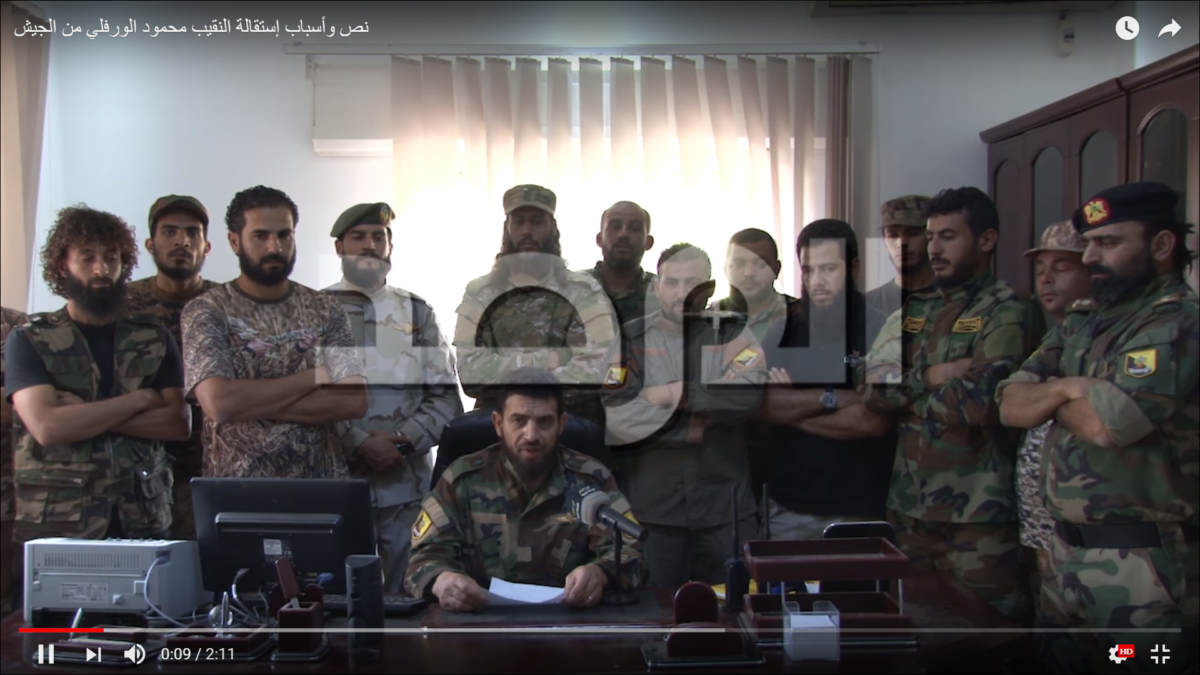

Werfalli announced his resignation on May 15 in a video published on YouTube, though the reason why is unclear. There has been chatter that it may have to do with an attack on a police station in Benghazi by the Saiqa Brigade that left one officer dead.

On May 15, 2017, Werfalli announced his resignation. The reason as to why the Saiqa Brigae commander resigned unclear.

Following the ICC arrest warrant, the LNA arrested Werfalli, stating he was under investigation by a military prosecutor. The LNA said that it is ready “to cooperate with [the ICC] in informing you of the result and course of the judicial case”. The LNA statement did not mention whether it would hand over Werfalli to the ICC.

However, a spokesperson for the Saiqa Brigades dismissed the ICC arrest warrant, saying that the ICC should rather arrest the opponents of the armed group, Al Jazeera reported.

The Footage: Seven Incidents in Seven Videos

Al-Werfalli is charged with murder as a war crime under Article 8(2)(c)(i) of the Rome Statute, the treaty that established the ICC, which is the “Violence to life and person, in particular murder of all kinds, mutilation, cruel treatment and torture”.

The charge is based on seven incidents shown in seven separate social media videos. All of these videos have been found online. Each incident and video will be presented and discussed below, following the order of the arrest warrant.

Incident One

Link to the video on Check [geolocated].

The ICC arrest warrant states the following:

Mr Al-Werfalli, wearing camouflage trousers and carrying a weapon, is seen in a video footage to stand near a hooded, unidentified person, who is moving around an open dirt area with his arms in the air. Mr Al-Werfalli is heard saying “Put your hands up! Put your hands up! Put your hands up!”. After that, he shoots the hooded person with his left hand a number of times and the person falls on the ground. Mr Al-Werfalli approaches the body, shoots again the body on the ground for a number of times and states “You have been misled by he who did you harm. You have been misled by Satan”. The video depicting this incident was posted on Facebook on 3 June 2016.

The first video is still available online on Facebook, with a duration of 2:16. It has been watched almost 200,000 times as of writing this article, and shared over 5,000 times. The logo and the name of the Saiqa Brigades (Arabic: القوات الخاصة الليبية) is visible throughout the video.

A still of the video showing Werfalli, wearing camouflage trousers and carrying what appears to be a Russian-made PK machine gun, moments before he shoots an unidentified person.

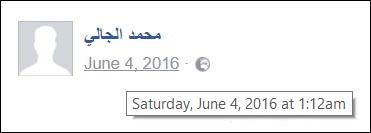

The source is a Facebook profile under the name Mohamed Al-Ghali with Facebook identification number 100012315483959 and username hamoalgali01. It is unclear whether this profile is the original source of the video. [Update: Al-Ghali has reached out to Bellingcat to specify that he was not the original source of the video]

The accompanying text with the video claims to show the execution of a Syrian national who is a member of the so-called Islamic State (IS). In the comments section, the user uploaded a photo seemingly of the executed individual at the same scene.

The upload time of the video to Facebook is June 4, 2016, at 1:12 am local time in Benghazi. This means there is an inconsistency with the arrest warrant’s claim that it was uploaded on June 3, though this may have to do with the time Facebook displays as your local time zone based on your computer time. If you figure out what time settings your computer is in, there are plenty of useful online tools to convert different time zones.

It is unclear when this video was recorded, though it must have been before June 4, 2017.

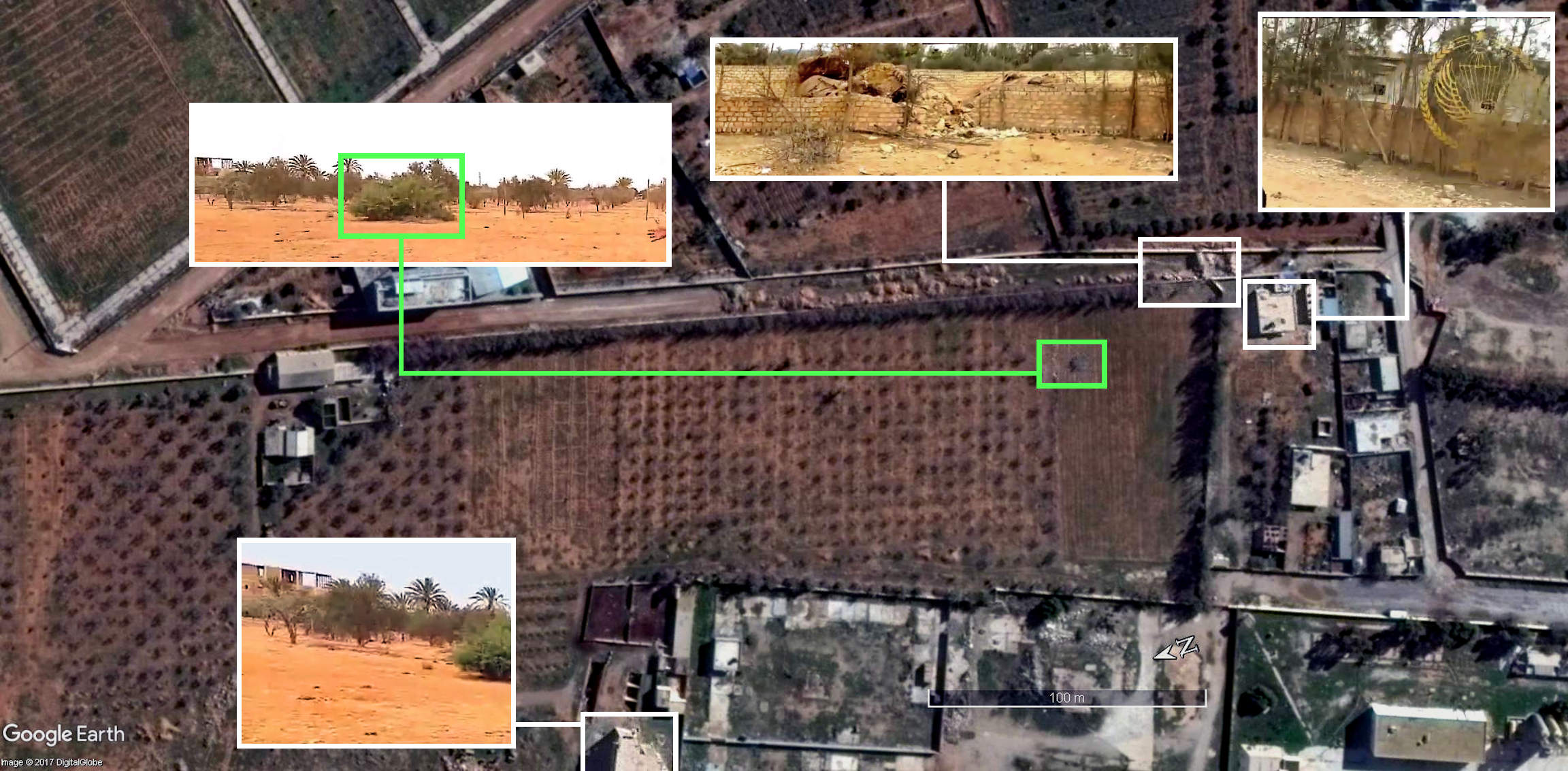

The exact location of this execution site is at 32.014221, 20.113838 (Google Maps, Wikimapia), an orchard in between the Benghazi suburbs of Al-Hawari and Al-Qawarishah.

A stitched panorama of still from the execution video gives a wider perspective of the area, which is useful for the geolocation process. Visual clues are the buildings on the left and right edge of the photos, the orchard, the two lines of trees next to what appears to be a narrow road, and an electricity pylon in the background.

The video was geolocated by Bellingcat’s “Daniel”, who first made a map of what was visible in the video.

Bellingcat’s Timmi Allen created the following image showing some of the elements of the video that match the satellite imagery of the area.

Incident Two

The ICC arrest warrant states the following:

Mr Al-Werfalli, wearing camouflage trousers and a black t-shirt with the logo of the Al-Saiqa Brigade, and carrying a weapon, is seen in a video footage shooting with his left hand three male figures in the head. The three persons are kneeling in front of a wall with their arms tied behind their backs. After the bodies of the three men fall, Mr Al-Werfalli shoots at the bodies a few more times. Two of the victims are alleged to have been revolutionaries in Benghazi. The video depicting this incident was posted on social media on 20 March 2017.

The second video is available via YouTube as a 18-second clip, uploaded by a user named “Hassan Mahmoud” (Arabic: حسن محمود). It has been watched over 10,000 times at the time of writing this article.

Using Amnesty International’s YouTube Data Viewer, the exact upload time to YouTube can established at March 21, 2017, at 4:09 am local time in Benghazi. The date is inconsistent with the time mentioned by the ICC warrant, though this may have to do with the display date of YouTube and the actual uploading time (hence the importance of Amnesty’s tool).

It is unclear when this video was recorded.

The exact location of this street has not been found yet, but you can help trying to find the exact location. Hints and possible locations can be posted on Check, where there is a specific entry for the geolocation of this video.

Incident Three

The ICC arrest warrant states the following:

Mr Al-Werfalli, wearing camouflage trousers and a black t-shirt with the logo of the Al-Saiqa Brigade, and carrying a weapon, is seen in a video footage in a room, with others being present as well. He is standing next to an unidentified man in a white t-shirt, who is kneeling bare feet, with his hands behind his head. Mr Al-Werfalli shoots the person with his left hand in the head and continues to do so after the man falls down. The men around Mr Al-Werfalli cheer in approval and another unidentified man from the group comes forward and shoots the victim two more times. The videos depicting this incident were posted on social media on 7 and 8 May 2017.

The third video is still available online on Facebook, and its duration is 1:17. It has been watched over 32,000 times and shared 242 times at the time of writing.

The source is a Facebook profile going by name Bin Mansour with Facebook identification number 100012980119097. It is unclear whether this profile is the original uploader of the video.

The accompanying text with the video claims to show the execution of “one of the Kharijites” by Werfalli.

The upload time of the video to Facebook is May 7, 2017, at 5:12 pm local time in Benghazi, which is consistent with the time mentioned in the ICC warrant.

It is unclear when the video was recorded.

The exact location of this house has not been found yet, and may be close to impossible without insider knowledge. You can help trying to find the exact location. Hints and possible locations can be posted on Check.

Incident Four

Link to the video on Check [geolocated].

The ICC arrest warrant states the following:

Mr Al-Werfalli is seen in a video footage in an outdoor setting together with two other men who carry weapons and whose heads are covered. The three men stand behind two other men, who are dressed in camouflage and are kneeling bare feet on the ground. The two men are claimed to be, the first, a member of the BRSC, and the second, possibly a member of Ansar al-Sharia. The two men can be seen earlier in the video footage being detained in a cage. Mr Al-Werfalli is seen walking away from the kneeling men, while the other two men with firearms walk towards them. Mr Al-Werfalli has his left hand in the air and sweeps it down towards the ground in a manner that suggests that he is ordering them to proceed with the execution. The two men shoot the kneeling persons who fall on the ground. The video depicting this incident was posted on social media on or about 22 May 2017.

The fourth video is also still available online on Facebook, with a duration of 2:47. It has been watched almost 37,000 times and shared 340 times as of writing this article. Only the last 9 seconds of the video show the execution, and the rest of the video shows interviews with the two individuals who are claimed to be members of the BRSC and Ansar Al-Sharia.

The source is the same Facebook profile as the one that posted the video showing Incident One. It is unclear whether this profile is the original source of the video.

The accompanying text with the video claims to show “the execution of the death penalty” (Arabic: تنفيذ حكم الإعدام) in Benghazi of a BRSC member and an Ansar Al-Sharia member.

The upload time of the video to Facebook is May 22, 2017, at 11:27 am local time in Benghazi. This date is consistent with the date mentioned by the ICC.

In the fourth video, Werfalli is seen in an outdoor setting with two other men wearing balaclavas. They stand behind two other men who are claimed to be a member of the BRSC and Ansar Al-Sharia. Werfalli orders the two man wearing balaclavas to proceed with the execution of the two other men.

The execution site has been geolocated by Twitter-user @5urpher to a compound in Al-Hawari, a southern suburb of Benghazi. The coordinates are 32.046755, 20.116750 (Google Maps, Wikimapia).

A satellite image of Google Earth of the compound in southern Benghazi where the execution shown in the Incident Four video took place.

It is unclear when this video was recorded, though once it is geolocated it may be able to determine an approximate time of the day based on the clearly visible shadows.

Incident Five

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=1&v=kievfxloCcU

Link to the video on Check [geolocated].

The ICC arrest warrant states the following:

Mr Al-Werfalli, wearing a full camouflage uniform, is seen in a video footage in an outdoor setting together with five men wearing hoods and camouflage trousers and holding firearms. Those five hooded, armed men stand behind four other hooded men, who are kneeling barefoot on the ground with their hands behind their backs. They point their firearms at each kneeling person’s head. Mr Al-Werfalli raises his left hand in the air and sweeps it down towards the ground in a manner that suggests that he is ordering them to proceed with the execution. The five men shoot the four kneeling persons, who fall on the ground. The video depicting this incident was posted on social media on 9 June 2017.

The fifth video can be found online on Facebook, uploaded by someone using the username “aalathry1” with Facebook identification number 1797850107. The execution takes place in the last 47 seconds of the video.

The video was uploaded on June 9, 2017 at 2:29 pm local time in Benghazi. This date is consistent with the ICC warrant.

The exact date when this execution took place is unknown.

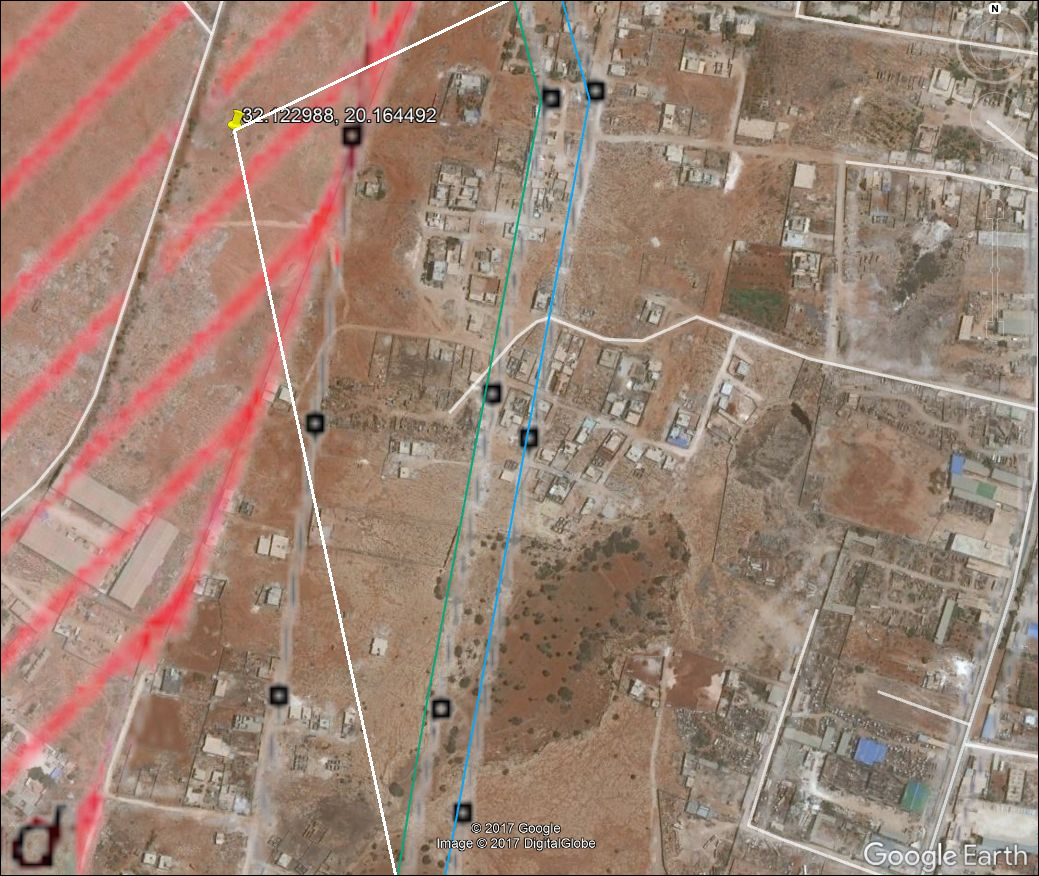

The exact location of this execution site has been geolocated by Twitter-user @5urpher to a military compound between Benghazi and the airport. The coordinates are 32.122988, 20.164492. The location was found by using the lines of electricity of OpenStreetMap in Benghazi.

The location of Incident Five (yellow pin) in Google Earth, with an overlay of electricity pylons (black squares).

Incident Six

The ICC arrest warrant states the following:

Mr Al-Werfalli is seen in a video footage in an area of desert together with two other men who are holding firearms. They stand behind two other persons, who are kneeling on the ground with their hands behind their back. Mr Al-Werfalli is seen speaking into the camera and then raising his left hand in the air and sweeping it down towards the ground in a manner that suggests that he is ordering the two men to proceed with the execution. The men shoot the persons kneeling, who fall on the ground. The video depicting this incident was posted on social media on 19 June 2017.

The sixth video is available on both Facebook and YouTube with a duration of 59 seconds. The video has been watched 80,000 times on Facebook and 18,000 times on YouTube.

The Facebook source is a page – not an account – with username “Benghazi2”.

The YouTube source is a channel named “Libya Al-Mostakbal”, which has over 1,000 subscribers. The accompanying text states that the video was published on social media, suggesting Libya Al-Mostakbal reuploaded the video and is not the original source. It says that Werfalli is shown in the video, ordering the execution of two men on an unknown date at an unknown place.

The upload time of the video to Facebook is June 19, 2017, at 9:19 pm, which is consistent with the time mentioned in the ICC arrest warrant.

It is unclear when this video was recorded.

The exact location of this desert area has not been found yet, but you can help trying to find the exact location. Hints and possible locations can be posted on Check, where there is a specific entry for the geolocation of this video.

Incident Seven

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oMfohLyw8d8

The ICC arrest warrant states the following:

Mr Al-Werfalli, wearing a black cap, camouflage trousers and a black t-shirt bearing the logo of the Al-Saiqa Brigade, is seen in a video footage, together with two other persons wearing camouflage trousers, black t-shirts, and holding firearms. Mr Al-Werfalli is holding a white document from which he reads. He refers to the document as a “Decree decision” which “shall be executed today 17/07/2017”. The video also depicts 18 persons wearing orange jumpsuits and black hoods, with their hands tied behind their backs, kneeling bare feet on the ground, in four lines. After reading the document, Mr Al-Werfalli says “Attention! The first group!” and then “Ready! Aim! Fire!” As he does so, five men in camouflage uniform, hooded, and carrying firearms, walk from behind the group of kneeling persons to the front and position themselves behind the first line of five kneeling persons. They raise their firearms at them and shoot. The persons fall on the ground. One person in the second line also falls. The shooters then return behind the group of the other kneeling persons. Then Mr Al-Werfalli is recorded saying “The second group! Ready! Aim! Fire!” As he does so, five men walk again from behind the group and position themselves behind the second line of five kneeling persons. The person who has collapsed during the first shooting is pulled back to his knees by one of the men. The five men then raise their firearms and shoot the five kneeling persons, who fall on the ground. The shooters then return behind the group of the other kneeling persons. When Mr Al-Werfalli says “Attention! Attention, the third group!” and “Ready! Aim! Fire!” five men walk again from behind the group, position themselves behind the third line of five kneeling persons, raise their weapons and shoot them. The persons fall on the ground and the shooters return behind the group of the remaining kneeling persons. Mr Al-Werfalli and the two other persons wearing camouflage trousers, black t-shirts, and holding firearms then walk behind the final line of three remaining kneeling persons. Mr Al-Werfalli is seen to still hold the white document from which he has read earlier. Mr Al-Werfalli and the other two men raise their firearms and shoot the three kneeling persons, who fall on the ground. He and one of the other men fire some additional shots towards the persons on the ground before walking away. In the same video, in a new segment, Mr Al-Werfalli, wearing a black cap, camouflage trousers and a black t-shirt bearing the Al-Saiqa Brigade logo, is seen together with two men wearing orange jumpsuits and black hoods kneeling on the ground. One of the two kneeling men has his hands in front of him while the other has his hands on the back of his head. Mr Al-Werfalli is holding a white document folded in his hand. He is recorded saying “Ready! Aim! Fire!” As he does so, two hooded men in camouflage, carrying firearms, walk forward, raise their weapons and shoot at the two kneeling persons, who fall on the ground. The men fire some additional shots at the victims before walking away. The video depicting this incident, involving in total 20 executed persons, was posted on social media on 23 July 2017. The data indicates that the video may have been uploaded in the Benghazi area, in Libya.

The seventh and last video is also still available online. A 4:46-long video was posted to Facebook by the same account that posted the Incident One and Incident Four videos. Segments of that video have been used by several other YouTube accounts from media organisations. It is unclear whether this profile is the original source of the video(s).

The accompanying text with the video claims to show the execution of twenty “terrorists” sentenced to death because they were allegedly involved in kidnapping, torture, killing, bombing, and slaughtering.

The upload time of the video to Facebook is July 23, 2017, at 5:14pm local time in Benghazi, which is consistent with the time mentioned in the arrest warrant.

It likely that the execution took place on July 17, 2017. The accompanying text with the video claims it was filmed in Benghazi.

The exact location of this location has not been found yet, but you can help trying to find the exact location. Hints and possible locations can be posted on Check, where there is a specific entry for the geolocation of this video. A stitched panorama shown above may be of help. The buildings in the upper side of the panorama are a potential clue to the location.

The Promise and Perils of Open Source Evidence

The Promise: A Goldmine of Potential Evidence

The widespread proliferation of new communication technologies, such as smartphones connected to the Internet, has increased the already unprecedented amount of information available about many of today’s conflicts.

Whether it is an onlooker who recorded an airstrike on his or her mobile phone, or a militant group that filmed an offensive for propaganda purposes, the material is very often published on the Internet and, specifically, social media. It may be that possible human rights violations are recorded in that footage.

Once corroborated and triangulated, this open source information can be a potential mine of evidence. Some jurisdictions have already used it to convict a suspect. A Swedish district court, for example, convicted a Syrian national of shooting a person with an assault rifle in 2012, partly basing the judgement on a video that was posted to Facebook. The man was sentenced to life in prison.

The international community has limited ability to collect impartial information and freely assist civilians inside many of today’s conflict zones like Myanmar, Syria, and Iraq due to restriction of movement. With the decrease in international observers that are able to conduct field investigations, open source evidence is promising. Open source information enables anyone with an Internet connection to mine information from places that were once blind spots. International human rights courts and tribunals “have expressed hope that new information technologies might bring about better, cheaper, and safer prosecutions,” Keith Hiatt writes in The Yale Law Journal.

Nevertheless, there are also methodological challenges of using open source information in legal cases, such as reliability, availability, and security, which will be discussed in the next section.

The Perils: Reliability, Availability, Security

Some of these challenges have been outlined by academics, including Hiatt in the aforementioned article, as well as by Emma Irving in an Opinio Juris article as a reaction to the ICC arrest warrant.

Firstly, open source information is “notoriously susceptible to problems of verifiability, which naturally affects its reliability in any kind of criminal proceeding” (Irving). Questions that arise may be the establishment of the exact time, date or location of the evidence, or even potentially digitally altered footage.

However, there is a wide variety of tools and methods which can be used to determine the exact location of a video or photograph, and sometimes even the approximate date and time. Verifiability is a challenge that can be overcome in many cases. It is unclear whether the ICC knows the exact location of the execution sites.

With the rapid development of technology and artificial intelligence, a new challenge is on the horizon: Can we be sure a person seen in a video is in fact the same person the video purports to depict? Offenders have been incorrectly identified before, as in the aftermath of the Boston Marathon bombing or the assaults at the Charlottesville white supremacist rally. Even more worrying is the possibility to produce a photorealistic video, say, of former US President Barack Obama speaking sentences he never said.

But neither of these issues are a challenge in the Werfalli case. Most, if not all, of the footage mentioned by the ICC appears to be produced – and shared – by individual members or supporters of the Saiqa Brigade.[1] The more salient question here, if this case goes to trial, is whether the defence team will contest the authenticity of the footage, according to Hiatt. In many international criminal cases, Hiatt says, “the issue is not whether the atrocity occurred, as a matter of actual fact. Instead, it is the context that matters.” For example, was there a fair trial before the execution, or not? That question is unlikely to hinge on whether an execution video was authentic. Indeed, the contested elements of a crime under the Rome Statute are more likely to concern chain of command, or the widespread, systematic nature of a criminal act.

Secondly, the availability of open source information may be another challenge. While the arrest warrant for Werfalli was issued shortly after the alleged crimes, human rights tribunals are usually only established after the cessation of hostilities. “As a result, today’s investigations concern yesterday’s atrocities,” as the formation of these tribunals may take years (Hiatt).

This can be a problem, as was highlighted by YouTube’s recent removal of many videos, playlists, accounts, and channels documenting conflict zones. As outlined in a New York Times article, YouTube “inadvertently removed thousands of videos that could be used to document atrocities in Syria, potentially jeopardizing future war crimes prosecutions.” The same has happened with videos from other areas where human rights violations are reportedly happening, such as Myanmar.

For that very reason, it is important to preserve, for the long term, open source documentation relating to possible human rights violations and other crimes. Projects like the Syrian Archive are entirely focused on this, and Bellingcat hopes to broaden these efforts to other conflict areas in the future too. (Also, as you may have noticed, most of the hyperlinks in this article link to archived versions of the original page in case a source is taken offline).

The Syrian Archive is entirely focused to preserve, for the long term, open source documentation relating to possible human rights violations and other crimes.

A third challenge is security. Open source evidence may increase threats for eyewitnesses and those who gathered the information first-hand, or even bystanders visible in a photo or video. As Hiatt said,

“By using these materials, investigators may draw unwanted attention to people depicted in them. The disclosure of a photograph to a powerful defendant or a hostile government might expose the identity of a witness, or otherwise endanger third parties.”

This challenge does not seem of particular relevance to the Werfalli case, as all of the material appears to have been recorded and subsequently disseminated on social media by members or sympathisers of the Saiqa Brigade themselves.

In case eyewitnesses are used, the use of open source evidence may actually decrease the risk for eyewitnesses as fewer witnesses may have to testify, and in case they do their claims can be corroborated with open source information.

The fourth and last challenge is forward-looking, and was put forward by Irving: the weight of evidence. Will the approach to open source evidence change depending on the stage of proceedings?

“The standard of proof for the issuance of an arrest warrant is ‘reasonable grounds to believe’ (Article 58(1) of the Rome Statute). One might assume that the approach to open source evidence would not be stricter when it came to initiating an investigation (‘reasonable basis to believe’, Article 53(1)(a)) but the situation may be different as regards the higher standards of ‘substantial grounds to believe’ (confirmation of charges, Article 61(5)) and ‘beyond reasonable doubt’ (conviction, Article 66(3)).”

Will it be the case that the higher the burden, the lesser the chance that open source evidence can meet it? The decision on the arrest warrant was not the place to answer such questions, but they will need to be addressed in future.

Discussion

Human rights organisations like Amnesty International welcomed the arrest warrant, stating the ICC’s decision is “a significant step towards ending the rampant impunity for war crimes in Libya.” Amnesty International has previously reported on potential war crimes committed by the LNA.

The US, the UK, and France welcome the ICC arrest warrant in a joint statement. This statement can be read in two possible ways, Alex Whiting writes for Just Security.

The first is that “the U.S. (a non-State Party of the ICC) is joining two ICC State Parties [France and the UK] to support and encourage a positive and pro-active response to the ICC warrant [..meaning..] support for the Court consistent with U.S. law […] as long as it is in the national interest.”

The second and more plausible read of the joint statement is, according to Whiting, that the US, France, and the UK, “are looking for a way to avoid the ICC. If the LNA did in fact pursue a proper investigation and prosecution of Al-Werfalli for the crimes for which he is charged, an unlikely proposition to be sure, it could render him ineligible to be prosecuted at all by the ICC.”

The Werfalli case has also potential implications for the US and other states engaged in Libya, since General Haftar is a dual US-Libyan citizen, Whiting notes. For more information on this issue, Whiting’s article is recommended reading.

On Libyan social media, criticism has been raised about the ICC’s arrest warrant. Questions are asked publicly about why “the heroic” Werfalli – who killed alleged Islamic State militants – would be prosecuted. Why are his enemies not prosecuted? Or, for instance, why not culprits of the forced displacement and killing of the Rohingya in Myanmar, or occupation forces in the West Bank?

Crimes committed in these areas may have been recorded and, for example, have been uploaded to YouTube. If these videos are deleted by YouTube’s AI, the platform risks losing “the richest source of information about human rights violations in closed societies” Hiatt told the New York Times. The ICC faced similar criticism from many top African officials, who accused the court of solely targeting their continent.

Either way, the decision of the ICC to rely on social media to support an arrest warrant is an important development, and may be only the beginning of a much larger increase of open source evidence by the Court. Open source information is a promise too important to ignore.

[1] However, there have been cases in which armed groups were imitated by others, such as a video in which militants from the Ukrainian Azov Battalion threatened the Netherlands. That video turned out to be fake.

Special thanks to Keith Hiatt and Thomas Feneux.