Mystery Spill At Mosul Lake: Analyzing Potential Causes Of Pollution

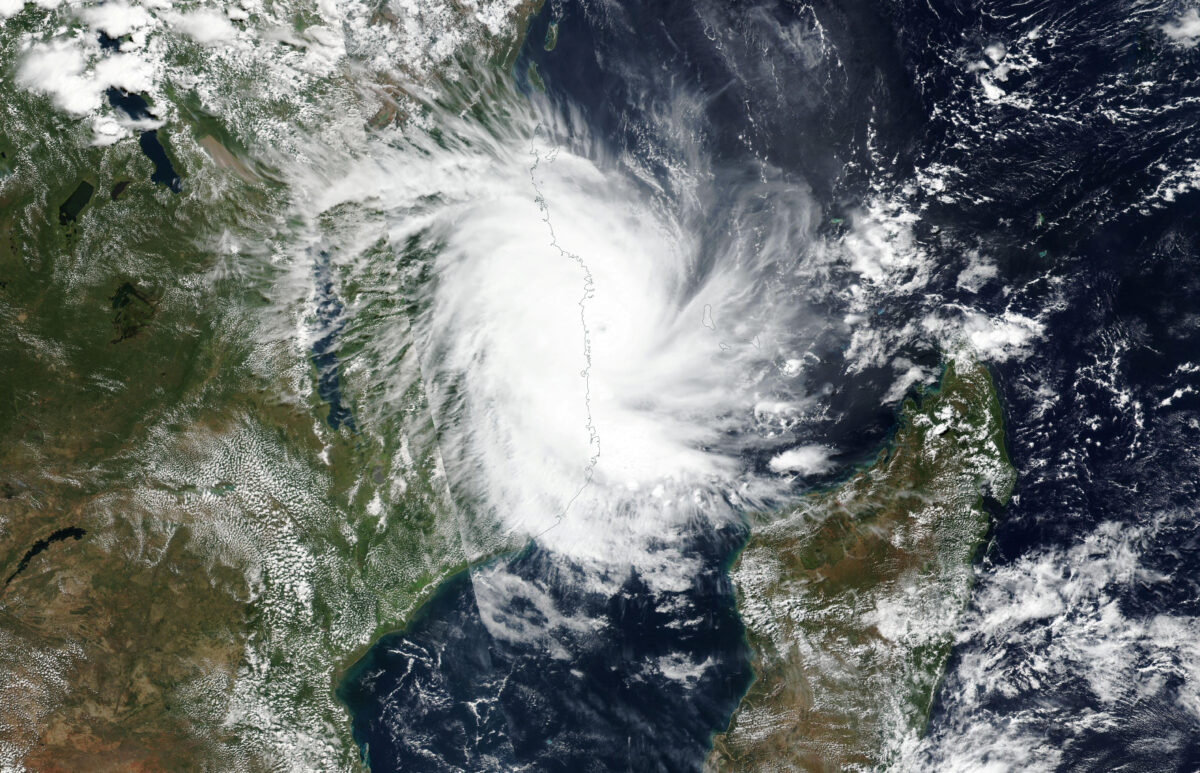

During the monitoring of the ongoing situation in Syria and Iraq via open-access satellite imagery, a curious situation presented itself in early January at the Mosul Lake. A black sludge stream resembling an oil spill appeared in the northwest part of the lake.

Mosul Lake, January 10, 2019 with Sentinel-2. Sentinel Hub

The sludge stream disappeared late January, only to show up again on February 3, 2019. Earlier, in January of this year, we published a post on Bellingcat showing that torrential rains in November and December led to severe oil pollution in northeast Syria, as rivers of dumped oil waste overflowed and contaminated agricultural land. Could the situation at Mosul Lake have been related?

Timelapse of oil spills in creeks flowing over agricultural land. Source: Sentinel Hub

This article explores what the potential origin of the mysterious black sludge could be, using all open source information available. It’s an attempt to analyze what information can be gleaned from open source data, including both imagery and peer-reviewed papers on the subject, as well as an experiment in utilizing all available means to monitor and identify potential environmental damage. Enjoy the ride!

Mosul Lake At A Glance

The Mosul Lake is a large water reservoir used for hydro-electricity generation via the Mosul Dam, which was built in the 1980s by Saddam Hussein and described by some as “the most dangerous dam in the world.”

During the rise of the so-called Islamic State in June 2014, there were major concerns over a possible breaching of the dam, which would have created a deluge and major humanitarian disaster affecting millions of Iraqi citizens living south of the dam and all the way up to Baghdad — as modelling predictions by the European Union showed. After ISIS was driven from the dam, maintenance and repairs continued to prevent such a disaster from happening, yet the dam remains a large environmental security risk in Iraq.

Mosul Lake. Source: Google Earth

The lake itself goes through various stages throughout the year, depending on rainfall and capacity to handle the influx of water by the dam. The Tigris river flows in from Turkey at the northwest side of the lake, while other smaller rivers and creeks flow into the reservoir from Dohuk and north east Syria.

During the dry season, the west part of Mosul Lake turns into a delta, where the land is used for agriculture and is an important bird habitat according to a 2010 analysis by Nature Iraq. Prior to the conflict in Iraq, there were already existing concerns over pollution of the lake, which originated from Dohuk and included discharged wastewater and other pollutants.

So, what did we witness on the satellite imagery in January? After studying the imagery, consulting experts and thinking over what the alternatives could be, we currently have two running theories which we will explore below.

Theory 1: Oil Pollution

The most obvious call to make is to link the visible black stream with oil pollution, considering the color and pattern of its presence on the surface water. If so, what could be the origin?

We believe there are two possible sources for the oil. Based on satellite imagery, we can see the first black spill coming in from a wadi west of the lake. A creek coming in from Syria’s Jazira canton ends up in this wadi. In Syria, the creek flows past the Suwaydyah oil refinery in Syria and an oil processing facility near the village of Ibrahim Khuki in Iraq, which is part of the Ayn Zallah oil field infrastructure. These sites and the creek are visible in this image:

Illustration of river flowing from Rmeilan oil fields to the wadi at Mosul lake. Source: Google Earth and Apple Maps

The Rmeilan oil fields in north east Syria are notorious when it comes to oil spills and pollution, which worsened after the start of the Syrian civil war. With limited options of safely refining and exporting the crude oil, a significant part of the oil industry is crippled without proper oil storage capacity and environmental management of the waste products. According to an interview with local authorities responsible for oil operations in 2016, the pumping jacks are turned on and pump up oil regularly to prevent them for getting rusty, and the extracted oil is dumped. It’s not clear if these practices are still occurring, although satellite imagery does show significant spills at various locations that only seem to increase through time.

Pumping jacks and oil spills at Rmeilan oil fields. Source: Apple Maps

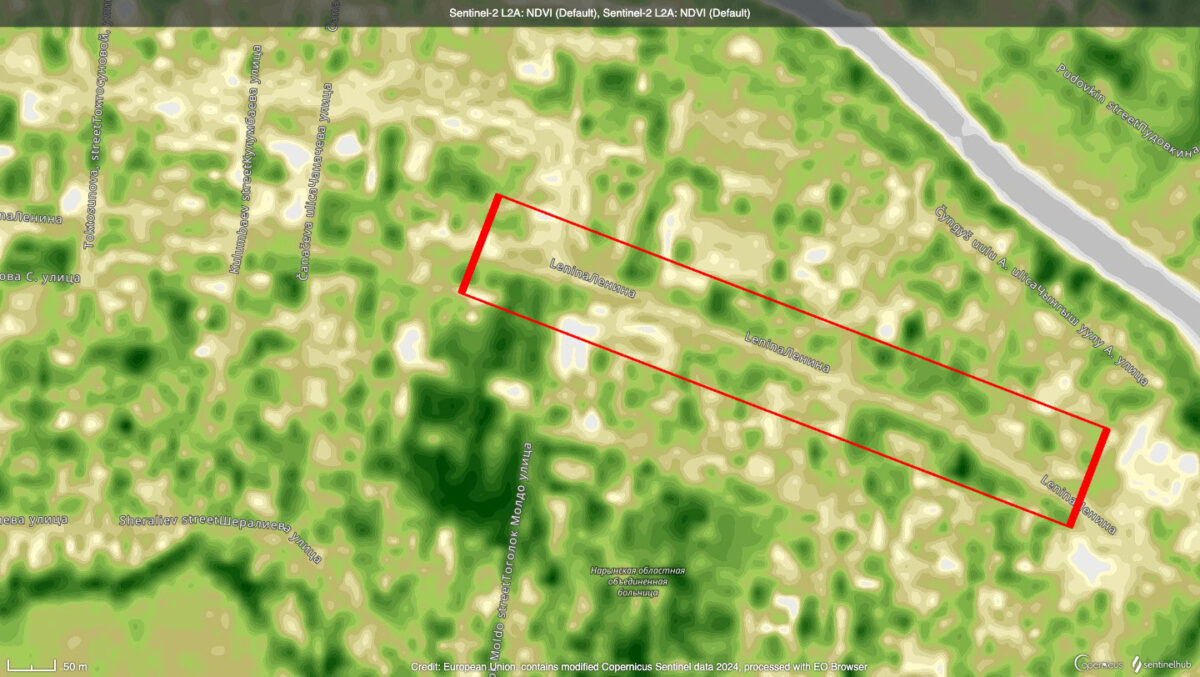

Using Sentinel-2 imagery, we can see the black rivers south and north and east of the Suwaydyah refinery, as well as several other creeks from areas nearby pumping jacks flowing into the main river. We used the Vegetation Index from Sentinel’s Hub EO Browser to demonstrate the likelihood that the rivers are full of oil waste:

Rmeilan oil fields near Suwaydyah, Sentinel-2 with Vegetation Index. February 6, 2019. Source: Sentinel Hub

There are various sources of high resolution imagery available. Apple Maps, for example, have images online which seem quite recent — most likely from 2017 or 2018, as they feature new structures that were not there before 2016. In this imagery we can see potential clues which seem to confirm the suspicion that’s it’s indeed oil waste water coming from the refinery and nearby pumping jacks, as the creeks are filled with a black substance (water would be more greenish on satellite imagery):

Suwaydayah oil refinery, north east Syria. Source: Apple Maps

Other high-resolution images from 2018 confirms this suspicion

Oil spills and dumpings at Suwaydiyah oil facilty in north-east #syria polluting local rivers and creeks https://t.co/zvODwSHZbw pic.twitter.com/2WvOaac6Vx

— Wim Zwijnenburg (@wammezz) March 7, 2019

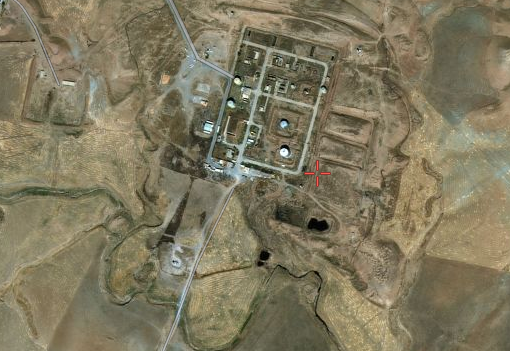

At the roughly 5 km mark into Iraqi territory, the creek flows past the oil processing facility at Ibrahim Kukhi, located here. This facility seems to be suspect number two in terms of the dumping of oil wastewater and is part of the Ain Zallah oil field, likely a pumping or processing station. Ain Zalah oil field, located south of Mosul Lake, became infamous as it was the first major oil field ISIS set fire to in August 2014:

#داعش تحرق حقول النفط في #عين_زالة في #زمار في شمال #نينوى قبل هروبها من #البشمركة #TwitterKurds#Peshmerga#ISIS pic.twitter.com/8Zep9W65lV

— Peshmerga #KIRKUK (@KURDISTAN_ARMY) August 28, 2014

Again, using images from Apple Maps, as well as other high resolution imagery, we can see the oil spills at the facility:

Ibrahim Kukhi oi facility, Iraq. Source: Apple Maps

Oil spills from a processing facilty at the Ayn Zalah oil field, north-west #Iraq, flowing into a local creek https://t.co/mSrRhlhc4L pic.twitter.com/89A0c94YYs

— Wim Zwijnenburg (@wammezz) March 7, 2019

The river flows from here all the way down to the wadi at the Mosul Dam. At the wadi entrance , we can see that on February 3, 2019, a black substance flows into the wadi from the creek, and then spreads further down the lake, as visible with both Planet Labs and Sentinel-2 imagery:

Overflow of the delta in Mosul Lake, time lapse with Sentinel-2, Sentinel Hub

Close-up of black substance flowing into wade, west of Mosul lake, February 3, 2019, Planet Labs.

Black substance in Mosul lake, February 4, 2019. Sentinel-2, Sentinel Hub

The black substance seems to spread further over the west part of the lake after that date. Cloud cover in ensuing weeks prevents further monitoring, and on the first Sentinel-2 image on February 19, the substance is gone.

Mosul Lake, February 19, 2019. Source: Sentinel Hub

We do not see a similar pattern of sludge coming in from the wadi and into the lake in the images from January, which indicates that February’s black sludge in the lake likely has a different source than the earlier incident.

We consulted various experts in oil and earth observation. Based solely on the pattern of behaviour in the water as well as the colour, they agreed that there is a strong possibility the February incident involves oil waste.

Normally, oil pollution can be detected with both optical and radar satellite imagery. Using radar imagery is outside our area of expertise and there are limited options to access this type of imagery outside Sentinel-1. Infrared bands can be applied, as thick oil on water absorbs heat from sunlight, and thus has greater emissivity than water, appearing as “hot” on IR bands. However, this depends on the type and thickness of the oil film on the surface.

In this particular case, if we are dealing with an oil related spill, it would probably be oil wastewater coming from the Rmeilan oil field in Syria or from the Ibrahim Kukhi oil processing facility. When we visited Rmeilan in November 2018, we witness oil wastewater spills creating a film on the water in the creeks which looked like this:

Oil spill in a creek at Rmeilan oil fields, November 24, 2018. Source: Wim Zwijnenburg

All of this means that an oil spill is less likely to be detected with infrared or near-infrared imagery, but let’s try nonetheless. Sentinel Hub’s EO Browser provides the option to use near- infrared (band 8) of Sentinel 2 imagery (Color Infrared) which shows the following output for February 4, 2019:

Black substance in Mosul Lake, February 4, 2019, with Vegetation Index, Sentinel-2. Source: Sentinel Hub

To sum up, what we observed in February seems to be consistent with an oil film on the water’s surface. The cause could be the heavy rains from later January that brought the oil wastewater all the way down to Mosul Lake from the Rmeilan oil field, or from oil dumps coming from the Ibrahim Kukhi oil facility, as the lake started filling with water after the dry period.

Verification on the ground would still be needed to make sure. We did reach out to contacts in Iraq who in turn reached to various Iraqi Ministries and/or staff working at the Mosul Dam, but the local sources reported that they did not see or hear anything related to the state of the surface of Mosul Lake. It should be noted that these sources did not go out and check the surface of the lake, so no ground verification was conducted, in the end.

We also scanned open source reporting and social media accounts for various key words in English and Arabic to see if any report on the situation at Mosul Lake was published, but did not find anything related. There was only the mention of the damage to the oil wells at Ayn Zalah by ISIS, southeast of the Mosul Dam, from 2014.

Theory 2: Natural Debris And Waste

To be sure that that we didn’t focus on what we merely wanted to see, we also checked if there were other, alternative explanations that could shed more light on what the black substance was.

Could it be just algae or another natural substance? The most likely alternative option we could come up with is crop residue and debris from the agricultural land in the delta from before it was flooded.

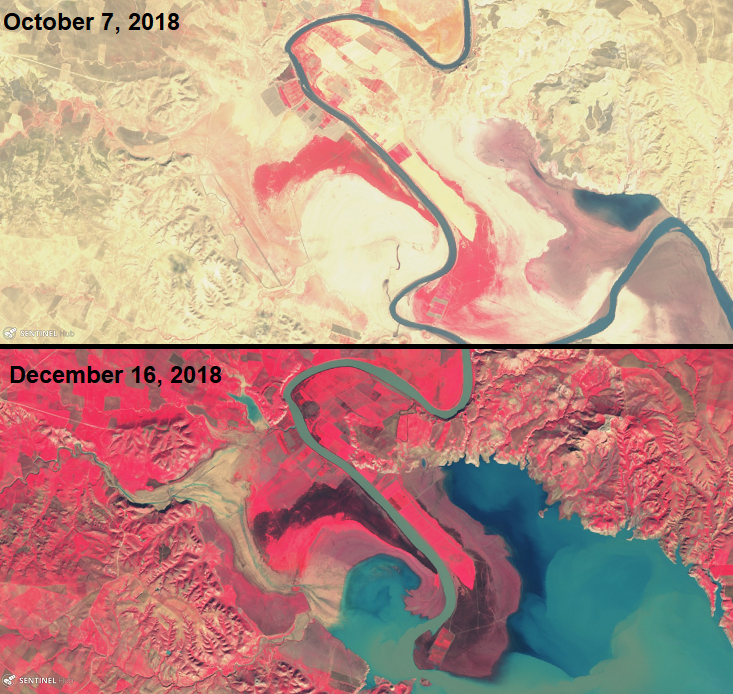

We started looking at what was happening in the area prior to the flooding in 2018, as well as double-checking imagery from 2017. We again used Sentinel-2 with Vegetation Index imagery from before the flooding of the delta, which shows there was vegetation on the land in the area — yet the patch of land became barren in December, turning black, as can be seen on this comparison of imagery between October and December 2018. We do not know what caused this area to blacken, but considering the gradual change from healthy vegetation to dark vegetation, it seems like a natural process that occurred after the rainy season started in November.

Time frame comparison of vegetation at Mosul Lake delta, 2018, Sentinel-2. Source: Sentinel Hub

Soon after the rainy season started and water coming in from the mountains in Turkey through the Tigris river started filling up the lake, the soil or substance on the soil started drifting on the water, creating the following flow:

Overflow of the delta in Mosul lake, time lapse with Sentinel-2 , Sentinel Hub

We double checked with available historic Sentinel-2 imagery and in, in March/April of 2017, a similar change was visible in this area — we see the same pattern of the dark soil and residues that are dissolving in the rising waters again:

Time frame comparison of vegetation at Mosul Lake delta, 2017, Sentinel-2. Source: Sentinel Hub

While looking for historic imagery of the delta, we also noticed a black substance in the western wadi in 2017. A close-up image of the wadi from Planet Labs shows the black substance flowing in from the wadi into the delta, which could also indicate that, in March and April 2017, there is potential oil (or waste) flowing in from the creek into the wadi and the Mosul Lake delta.

Black substance at wadi and delta of Mosul Lake, April 4, 2017, Planet Labs

Black substance flowing out of the wadi at Mosul Lake, March 25, 2017. Source: Planet Labs

In sum, satellite imagery indicated that vegetation growth in the delta in the dry season is the likely culprit — that explains the stream of dark residue in the lake on the January 2019 imagery, as we’ve seen similar issues occurring in previous years.

Solving The Mystery

Based on the information we have collected through open source satellite imagery, it seems there are multiple explanations for the black substance appearing on Mosul Lake’s surface in January. The first image from late January seems to indicate that the most plausible explanation is vegetation residue from the delta that surfaced when the influx of rainwater from the Tigris river started filling Mosul Lake. However, as the black substance was not visible any more in later imagery from January 15, 2019 and after, this did not explain the appearance of another stream of black sludge in the lake in early February 2019, as shown on Planet Labs and Sentinel-2 imagery below.

Black substance in Mosul Lake, February 4, 2019

Colour adjusted image of black substance in Mosul Lake, February 4, 2019, Sentinel-2. Source: EOS Viewer

The imagery does show black residue flowing in from the wadi in the west part of the lake. Thus, combined with additional rains in late January, a plausible explanation for the black substance in the imagery in February is that this is could be oil waste coming in from from the Rmeilan oil fields in Syria, or else from the Ibrahim Kukha oil facility. The spill dissolved after roughly two weeks, when the first imagery without cloud cover of the lake appeared online. Historic imagery from 2017 shows similar issues with likely oil coming from the creek into the wadi.

Other explanations also remain on the table — such as plant oil or certain type of algae, for example — but according to the experts we consulted, this seems less likely considering the pattern and reflection in various satellite bands. However, the experts underscored that only ground verification can determine the exact nature of the substance.

If it is indeed oil waste water from Syria, this certainly poses important questions over the situation in the oil fields of Rmeilan. Cross-boundary pollution caused by lack of maintenance of oil fields adds another dimension to the serious environmental impact of armed conflict.

The regional Self-Administration in northeast Syria is lacking significant resources to deal with its crumbling oil infrastructure. Proper pipelines, pumping systems, storage, and processing facilities are lacking due to the absence of import of materials, lack of expertise, and overstretched capacity to operate the oil infrastructure, while crucial work to clean-up and rehabilitate polluted sites is missing.

Regardless of whether or not Lake Mosul was affected by an oil spill, the research for this article has demonstrated the already severe impact of the conflict on the environment in the region. Furthermore, there are ongoing pollution issues in Iraq’s oil infrastructure, as waste dumping still frequently occurs, which can add to the wider environmental issues the country is struggling with, including water related pollution concerns that hit the south of Iraq this summer.

In conclusion: We have applied various open source satellite images to see if we could identify what the source was of the mysterious black sludge in Mosul Lake. Based on our analysis and additional consultation with experts, we think we have witnessed a combination of oil waste water, caused by either oil dumping or flooding of polluted rivers by the winter rains that washed the oil down to the Mosul lake, and vegetation residue from the delta lands that ended up in the water when the rains filled the Mosul lake.

We would like to thank Twitter users Samir (@Obretix) and Pierre Markuse (@Pierre_markuse) who provided major input during the research phase. Further thanks to Samir Madini (@Samir_Madani), Markus Enenkel, and Harel Dan (@HarelDan) for all the valuable insights and help. If you have any feedback or recommendation for further research feel free to contact the author via Twitter @wammezz