Water Filtration Plants and Risks of a Chlorine Mass-Casualty Event in Donetsk

Over the last two months, increased shelling in and around industrial sites north of Donetsk have, apart from the direct civilian casualties costs, posed huge public health and environmental risks. Apart from the wider environmental impacts caused by targeting industrial sites, on several occasions, Russia-backed forces have hit various water treatment stations. These facilities host a substantial amount of liquefied chlorine gas stockpiles used for water purification, a much-needed supply in cities lacking sufficient drinking water for the civilian population (including in Donetsk, which they control). Any direct hit on these stockpiles could possibly lead to a mass casualty incident with clouds of chlorine gas spreading over nearby populated areas. As fighting around sensitive sites in Donetsk are frequently erupting, it seems more a matter of time before this goes awfully wrong. This article will explore what these risks are, where it could occur, and what other water related problems could follow from targeting critical infrastructure

Background

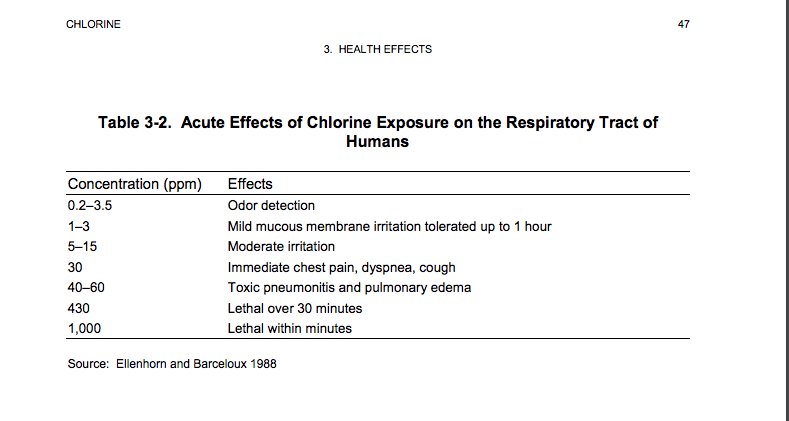

Chlorine is one of the most widely produced chemicals, and used for many industrial and household applications. At room temperature chlorine gas is yellow-green and due to its density will usually settle along the surface. Health risks associated with exposure to chlorine is mainly pulmonary damage of various degrees. Depending on the dose and time of exposure, this could lead to different impacts: the higher the parts per million (PPM), the more severe the impact, ranging from irritation of the mucus membranes at 1-3 PPM to pulmonary symptoms at 15 PPM, and fatal injuries at 430 PPM. Though exposure depends both time and dose, it is less realistic that people receive the lethal dose over a long period of time, unless trapped inside a location. A more comprehensive overview over health effects, decontamination and treatment to chlorine gas can be found in the US Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry’s profile of Chlorine

Weaponized chlorine has gained more popularity among State and non-State actors in the last decade. In 2006-2007, Al-Qaida in Iraq equipped chlorine trucks and suicide bombers with explosives and set them off, hoping to cause mass casualties. At least 13 attacks involving chlorine were reported in this period, though the chemical impact seemed to have been limited. During the recent conflicts in Syria and Iraq, there have been numerous reports of chlorine gas weapons used by both the Syrian government against civilians and the Islamic State in Iraq using chlorine in roadside bombs. In October 2016, the UN noted another incident where a water purification plant south of Mosul was hit, leading to cloud of chlorine gas that resulted in exposure of at least 150 civilians that sought treatment. And more recently, an accident with an exploding chlorine gas cylinder at a steel factory in Sulimaniya, Iraqi Kurdistan resulted in at 100 workers being poisoned to the toxic chlorine gas and needed medical care.

No water under the bridge

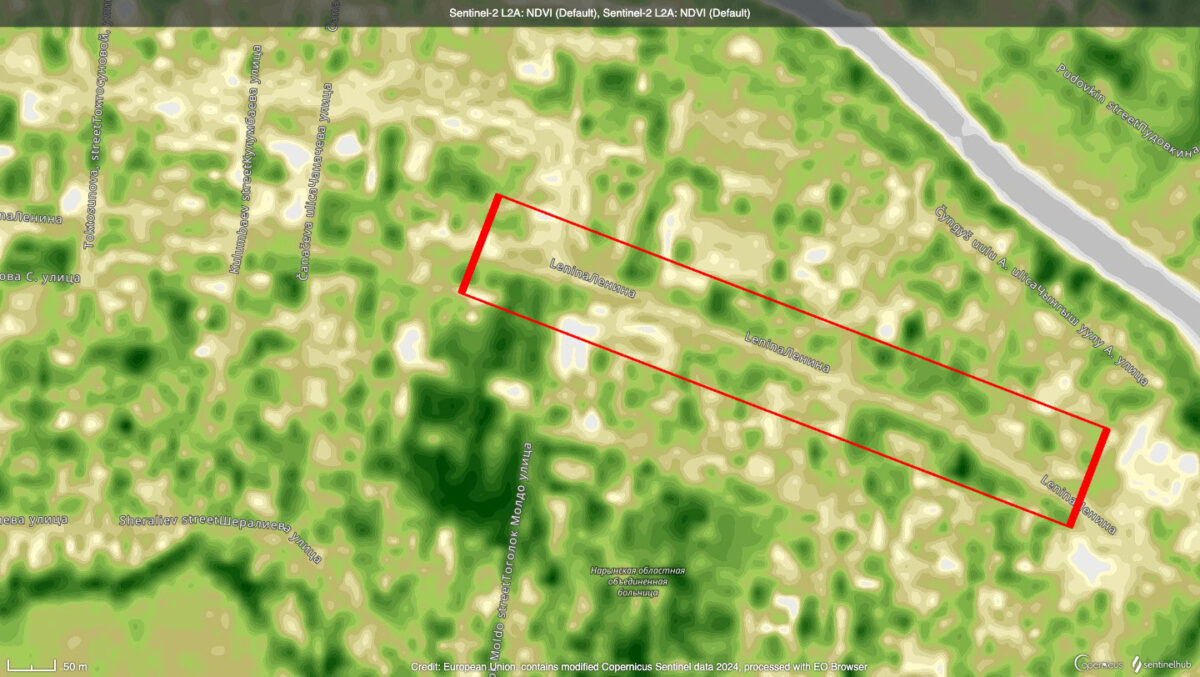

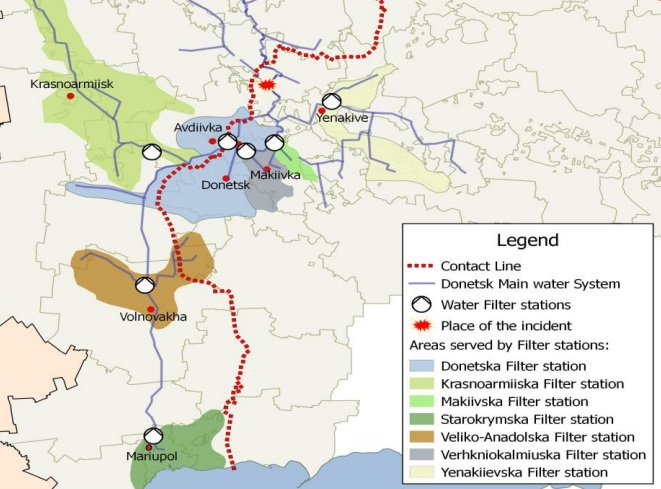

Mass casualty incidents, as a results of targeting critical infrastructure, have been an persistent threat since the outbreak of fighting in Ukraine, as there are several locations in and around Donetsk that are storing thousands of liters of chlorine gas. For example, the Verknyokalniuske Filtering Plant is reportedly storing 300 tons of liquefied chlorine for water treatment. Though these type of locations are usually located fairly remotely from populated areas, this plant is located in the vicinity, the closest is 1 km away, of residential neighbourhoods.

Verhkniokalmisuk Filtration Station

Apart from the direct impact due to the chemical hazards associated with the release of chlorine gas that could affect hundreds, there are also wider risks, such as lack of access to clean drinking water. In November 2014, shelling of power supplies to a water purification plant cut off access to drinking water to thousands of civilians. Continued targeting of critical water infrastructure sites, as well as power stations providing electricity to water pumping stations, resulted in severe risks for civilians, as was noted in the 2015 Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) Access to water in conflict‐affected areas of Donetsk and Luhansk regions report. This report noted that water was becoming a ‘potential source of conflict’ which should be prevented. It further describes numerous attacks on these infrastructures in 2014 and 2015, demonstrating how vital, and fragile, this type of infrastructures is.

One example in 2015 was a direct hit on the Pivdennodonbbasky water pipeline and power cuts disabling pumping station in two other major filtering stations that supplied water to various neighbourhoods in, and villages near, Donetsk. This resulted in the cut-off to clean water to 830.000 civilians in this area.

A similar incident whereby the a water filtration station in Donetsk was reported in May 2015 on Twitter, where a user upload an image of what was claimed to be an impact of some type of munition. But further information was lacking, so we were unable to verify at which location this occured.

Вчора на фільтрувальну станцію Донецька прилетів снаряд pic.twitter.com/2iZzYRsEUU

— AK (@erranta2_andrij) May 22, 2015

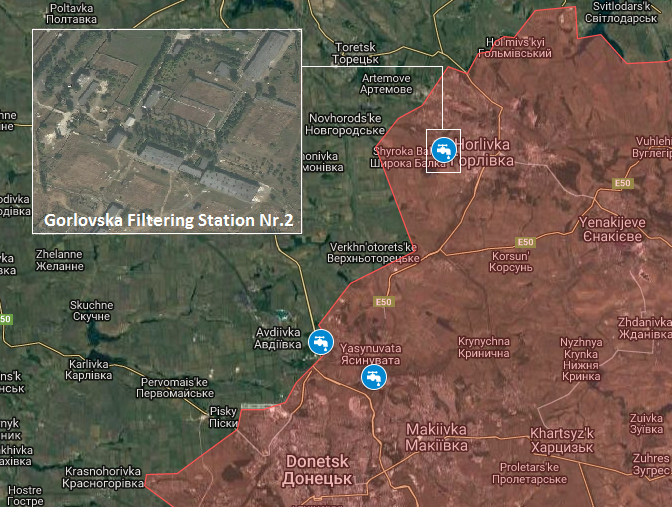

One other major filtration plant that is on the frontline is the Gorlovka Filter Station Nr. 2, which has been shelled numerous times in 2016, leading to a plea from the ICRC to stop targeting these facilities, as over 2 million people depend on them.

Gorlovska Filtering Station Nr. 2

Shelling of all these water filtration facilities continued throughout 2016 and into 2017, despite warnings by the OSCE, UNICEF ,and other humanitarian organisations over both the humanitarian consequences of destruction of key water infrastructure and the looming environmental disaster if stockpiles were hit.

WASH Cluster Map of Donetsk water systems. December 2016

Early March 2016, the Donetsk Filtration Station (DFS) at Yasinuvata was shelled and on-site operations had to be halted. On the 19th of December, another missile hit the building with water filters, and two other missiles ended up in fields nearby. Though the shelling did not halt the operation, it highlighted the risks of shelling of these facilities, and a warning [PDF] was send out by the UN WASH cluster and the UN Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) in a separate press release [PDF]. In the whole of 2016, there were 14 reported cases of shelling near/at the DFS.

Late January 2017, reports were coming in that the DFS was hit by another round, though the images could not be verified though other means. The OSCE monitored a couple of hundreds explosions in that area on the 29th of January 2017.

#ДФС, последствия обстрела 29/01/17 pic.twitter.com/OQuYa1D27h

— Necro Mancer (@666_mancer) January 30, 2017

On February 24, 2017, the DFS was targeted again , this time more seriously. Several 82mm mortar rounds targeted the water purification plant, which halted on-site operations. At that moment, the facility stored 8 cylinders of 900 litres of liquefied chlorine gas. The OSCE Monitoring Mission’s spokesperson stated that “An environmental disaster cannot be excluded either, with chlorine tanks at the plant potentially exposing the wider area to the release of poisonous gas”. In the overview of humanitarian bulletin released by OCHA early March 2017, the direct human health and environmental risks are stressed again, noting that:

“The nearly-miss hit of the chlorine gas depot at DFS on 24 February serves as a stark reminder of the risk for associated to presence of pollutant and chemicals for all those present in the area. Shelling hit the building where over 7,000 kg of chlorine gas is stored in bottles, and, fortunately, none of these were damaged. Should just one of the 900 kg-containers be damaged, any person present within 200-metre distance would be killed and those living within 2.4 km would suffer health problems. In case of extensive damage, people living within 7.4 km downwind from the facility would need to be evacuated within 24 hours, across the ‘contact line’

Early March 2017, the facility again received incoming fire, this time halting operations again for a short period, forcing the ICRC to step up the supply of water delivery by tanker trucks, and sending out a warning how this could affect the local population

Weapons fired on filtration plant were positioned inside the 15km withdrawal lines for 82mm mortars pic.twitter.com/da4cPEwpuo

— OSCE SMM Ukraine (@OSCE_SMM) March 3, 2017

These incidents starkly underline that indeed, mass casualty events could happen in case of direct hit. However, caution to not overstating the risks is warranted. As estimated by Dan Kaszeta, a chemical weapons expert consulted for this article, “it takes a lot of force to breach each cylinder to the point that it catastrophically dumps all of its inventory at one time”. He stated that is exceedingly unlikely in a shelling situation that all of chlorine inventory is going to get vented because of compartmentalisation of the chlorine in cylinders, and it is far more likely that damage to a pip of valve will result in a chlorine leak. As the nearest populated area is 2 kilometres away from the site, it’s less likely that there will be mass casualty risks as a result from targeting these locations, as the dose and exposure time would be fairly limited. Weather and wind conditions should also be taken into account in making a risk assessment of the fall-out area. Despite Kaszeta’s assessment, it is understandable that a ‘better safe than sorry’ approach has to be taken by the UN, as it’s unclear how extensive the shelling and subsequent damage to the chlorine storage can be, and threats to human health should be taken seriously.

Water conflicts and wider environmental concerns

These incidents over targeting critical infrastructure and huge human health risks also highlight, again, the grave concerns of chemical incidents that could occur in conflicts. As one expert coined the term ‘chemical warfare by proxy’, sites storing and utilising industrial chemicals could face both intentional targeting and subsequent acute and or long-term health risks. Unlike Iraq and Syria, it seems less likely that armed groups would use chlorine in weaponised forms against targets. However, it is deeply worrying that warring parties engage in shelling in and around industrial areas where critical infrastructure may be damaged or destroyed, leading to the halting of essential services like water purification and distribution, or acute health risks as industrial chemicals can be released, leaving civilians and risk of exposure. In Donetsk, damage to water purification plants, filtering stations and filtration plants has cut off clean drinking water to a population in need, which seems to have the biggest public health impact. Lack of clean water can put civilians in an very vulnerable situation. Disruption of water supplies and sewage systems deteriorate the public health situation, in particular for vulnerable groups with special needs, such as women and children who deal with menstrual hygiene or are more susceptible to water-related diseases. Current estimates by the ICRC and OCHA are that if there is a continued disruption of water supplies, either by targeting the pumping station, powerlines or water filtering stations, over 1.3 million people risk being affected.

In 2010, the UN General Assembly adopted Resolution 64/292, which explicitly recognizes the human rights to water and sanitation, and how this is essential to the realisation of all human rights. Furthermore, it called upon States to support countries in need with diverse means to provide safe, clean and affordable drinking water for all.

In August 2016, the UN Environmental Assembly adopted by consensus a resolution on Protection of the Environment in Areas Affected by Armed Conflict, which emphasises the strong nexus between conflict, environmental damage and how environmental degradation can affect vulnerable groups. Targeting industrial sites could directly and indirectly result in the creation of such a scenario. The resolution therefore called upon Member states to ‘cooperate close on preventing, minimizing and mitigating the negative impacts of armed conflict on the environment.´ Referring to this resolution, the Ukrainian Ambassador to the UNEA, released a statement on March 6, 2017, that referred to the dire situation the country’s population is currently in and stressed the need for international support in identifying and monitoring these environmental impacts of conflicts.

In a same concerned statement to the UN Security Council in 2016, the ICRC noted that “Armed conflict has direct and indirect impacts on people’s access to water – and both have a degrading cumulative impact on water supply over the many years of a protracted conflict. (…) Parties to conflict have an obligation to ensure that the basic needs of the civilian population are met and that their dignity is protected. Water is essential for a life with dignity and parties to conflict, government donors and humanitarian organizations must work together to support resilient urban services during armed conflict.”

This blog aims to provide information on how open-source methods could help monitoring such events, and inform a wider audience on the broader risks associated with targeting water facilities. We hope that identifying, mapping and and highlighting these risk will lead to improved awareness of these direct and long-term environmental health risks associated with conflicts, and the need tot incorporate these risks in post-conflict reconstruction and peace-building programs.

Thanks to Dan Kaszeta for his input and comments, and Foeke Postma for additional research and mapping.